INTRODUCTION

The number of endoscopic procedures has increased considerably due to the wide use of screening upper and lower endoscopy. The complexity of endoscopic procedures has also increased due to the wide adoption of interventional techniques such as endoscopic submucosal dissection and peroral endoscopic myotomy. More advanced techniques have in turn increased the need of sedation.1 The use of propofol for sedation during endoscopic procedures has increased in recent years,2 mainly because of its favorable pharmacokinetic profile compared with traditional endoscopy sedation drugs such as benzodiazepines and opioids.3,4 Propofol (2,6-diisopropyl-phenol) is a phenolic derivative with satisfactory sedative, hypnotic, antiemetic, and amnesic properties. Propofol is highly lipophilic and thus can rapidly cross the blood-brain barrier, resulting in an early onset of action (the drug can induce unconsciousness within periods as short as 30 seconds).5 The depth of sedation increases in a dose-dependent manner. As an additional advantage, regardless of the depth or length of the sedation period, propofol has a short recovery profile (recovery occurs within 10 to 20 minutes after discontinuation).5 Propofol has a short half-life (4 minutes vs. 30 minutes for midazolam).5,6 With regard to side effects, although propofol is generally associated with good hemodynamic stability, it can induce a dose-dependent decrease in blood pressure and heart rate. To date, no pharmacological antagonist has been developed.

In the United States, propofol is generally administered by anesthesia specialists, despite the evidence that endoscopists can administer or supervise the administration of propofol safely without the involvement of an anesthesia specialist.7,8,9,10,11,12 The administration of propofol by anesthesia specialists for routine endoscopic procedures is controversial because it adds significantly to the cost of endoscopic procedures without an established improvement in outcomes.13 On the other hand, the administration of propofol by endoscopists or supervision of its administration by endoscopists is controversial because anesthesiologists claim that it is unsafe.14 Concerns about the safety of endoscopist-directed propofol (EDP) have been voiced that propofol should be given only by healthcare professionals trained in the administration of general anesthesia.14 Here we discuss about the safety and drawbacks of EDP for routine endoscopic procedures.

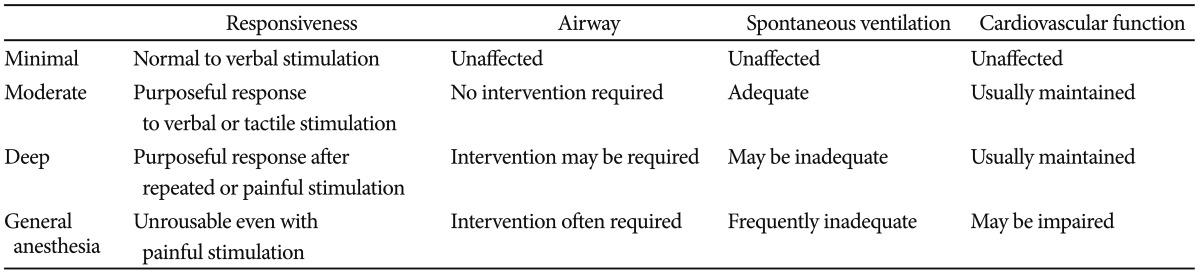

DEFINITION OF SEDATION

According to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), sedation and analgesia comprise a continuum of states ranging from minimal sedation (anxiolysis) through general anesthesia.15 It is important to recognize this continuum as summarized in Table 1. A change in the level of sedation from conscious sedation to general anesthesia may occur inadvertently with a relatively small alteration in the dose of sedative drugs used.16

SIDE EFFECTS OF PROPOFOL

Propofol possesses relatively little analgesic effect, and its amnesic effect is less pronounced than that of midazolam.7,10 Local pain occurs in 30% of patients during administration of propofol. This can lead to a fall in systemic vascular resistance and cardiac contractility and consequent hypotension.17 Propofol can reduce cardiac output without a concomitant change in heart rate.18,19 Respiratory depression can also occur with propofol use. Slow administration of propofol boluses has not been shown to attenuate these cardiorespiratory effects although using propofol as an infusion may do this.

Propofol can also give rise to myoclonic jerks and convulsions; these are usually very transient and occur as the sedative effects of propofol are wearing off.20,21 The metabolism of propofol is different in the elderly and the dose should be reduced in these patients. Impaired cardiac function also potentiates the effects of propofol but impaired renal or hepatic function does not affect propofol activity to a significant extent.21 In patients with cirrhosis, use of propofol for elective upper endoscopy does not precipitate encephalopathy.21

SAFETY OF ENDOSCOPIST-DIRECTED PROPOFOL

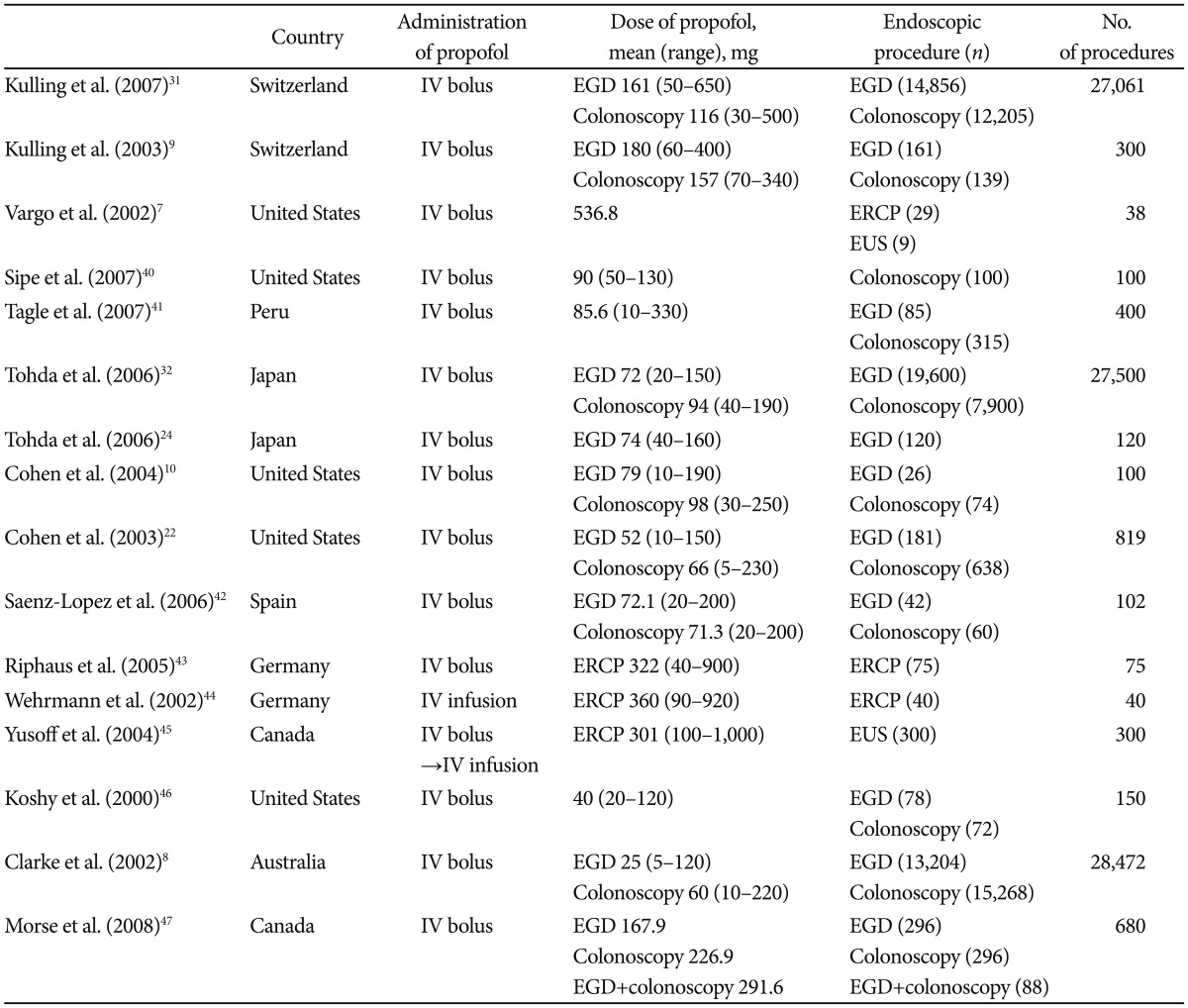

The method of choice for safe administration of propofol is by intermittent bolus. Safety literature has been developed primarily in the United States, Switzerland, and Japan (Table 2).1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 In the United States, EDP has been restricted largely to the states without nursing practice acts or laws prohibiting propofol administration by nonanesthesiologists. The largest volume of data has been collected by Heuss et al.11 and Kulling et al.31 in Switzerland, Tohda et al.32 in Japan, Walker's group in Medford, Oregon, and the group at Indiana University Hospital in the United States.20

Heuss et al.11 reported that the administration of propofol under the supervision of the gastroenterologist is safe for conscious sedation during endoscopic procedures. They observed 82,620 endoscopic procedures and there were no severe adverse effects.11 Cohen et al.22 reported that propofol could be safely and effectively administered under the direction of a gastroenterologist. They observed 638 colonoscopies and 181 upper endoscopies. Hypotension (>20 mm Hg decline in either systolic or diastolic blood pressure) developed in 218 patients (27%), and hypoxemia (oxygen saturation <90%) occurred in 75 patients (9%).22 All episodes of hypotension and hypoxemia were transient, and there was no need of assisted ventilations. Rex et al.,14 in a safety review of 646,080 EDP sedation cases (223,656 published and 422,424 unpublished), noted that endotracheal intubation and death occurred in 11 and 4 cases, respectively. There were no patients with permanent neurologic sequelae, although one patient had a tonic-clonic seizure, and one had a transient ischemic attack (blindness), both of which resolved without sequelae.14 They concluded that EDP appears to result in a lower mortality rate than traditional sedation with benzodiazepines and opioids, and to have a comparable rate to that of general anesthesia administered by anesthesiologists.14 The four deaths observed after EDP administration occurred in patients with ASA III or higher who were undergoing nonroutine medical procedures.14 Three of the patients had serious underlying medical conditions. The results suggest that such patients should be sedated by an anesthesiologist; however, nonanesthesiologists have successfully used propofol for patients with higher ASA classes, despite the higher risk associated with sedating these patients.

The current controversy surrounding performance of EDP and the cost of anesthesia specialists for endoscopy are focused on average-risk patients undergoing routine procedures. Patient factors almost certainly contributed to the reported deaths. Anesthesiologist-administered propofol for truly routine procedures in average-risk patients would be very costly and may be unjustified, because there were no deaths or permanent sequelae among such patients or procedures.

AN ALTERNATIVE METHOD FOR REDUCING THE SIDE EFFECTS OF PROPOFOL: BALANCED PROPOFOL SEDATION

Combining propofol with an additional drug (benzodiazepine/opioid/ketamine) allows the dose of propofol administered to be reduced without reproducible effect on recovery time.33,34 Administration of 'balanced propofol sedation' seems to be associated with less need for assisted ventilation, although this has not been demonstrated in head-to-head comparisons. It is clear, however, just from an observational standpoint, that balanced propofol sedation allows more moderate levels of sedation compared with single-agent propofol.1,7 During upper endoscopy, single-agent propofol titrated only to moderate sedation is frequently accompanied by coughing and gagging.7 These responses during upper endoscopy tend to cause endoscopists to administer additional propofol to drive patients into deep sedation. Although this has been reported safe in the literature, the need for mask ventilation seems to be greater when single-agent propofol is used. Balanced propofol sedation, or combination therapy, has several distinct advantages for EDP.5,7,32

First, it maintains a reversible drug component, because antagonists to both opioids and benzodiazepines are available. Second, it simplifies the administration of propofol, because even low doses of an opioid or a benzodiazepine result in reduction of the total dose of propofol by more than 50%. Third, administration of propofol is smoother because boluses are not only smaller but also given less often. Prospective studies have indicated that the actual incidence of deep sedation using balanced propofol sedation targeted to moderate levels is lower than when opioids and benzodiazepines are used without propofol.15,35 A randomized controlled trial in which single-agent propofol titrated to deep sedation was compared with balanced propofol sedation (targeted to moderate sedation) using fentanyl and propofol, midazolam and propofol, or fentanyl, midazolam, and propofol showed that the combination regimens could be successfully targeted to moderate sedation and that satisfaction was kept at a high level compared with single-agent propofol, with no lengthening of the time for recovery.1,5,36 In fact, patients who received combination therapy actually recovered faster than those who received single-agent propofol, presumably because they were recovering from only moderate sedation.

INTERMITTENT BOLUS INJECTION VERSUS CONTINUOUS INFUSION OF PROPOFOL

Continuous propofol-infusion is an alternative procedure for deep sedation with intermittent bolus application of propofol. Continuous infusion of propofol may be theoretically associated with a less need for user interventions, maintenance of a more consistent level of sedation, and probably a lower total drug dose required. Additionally, the avoidance of high peak propofol plasma concentrations, which occurred during bolus application, may reduce the intensity of the hypotensive effect of propofol. Furthermore, a rapid lightening of the sedative effect with subsequent patient movements may be avoided by only minimal fluctuations of the plasma propofol concentration under continuous infusion.

However, according to reported studies, continuous infusion of propofol holds no relevant advantages. Neither the total dose of propofol required nor the sedation efficacy or the frequency of side effects are improved by infusion versus bolus administration. Bennett et al.37 compared incremental bolus with continuous infusion of propofol for deep sedation during dentoalveolar surgery after induction with a bolus of midazolam/fentanyl, and found no significant differences in efficiency, safety, and recovery. However, in the continuous infusion group, a statistically higher maintenance dose of propofol (7.3 mg/kg/hr vs. 6.03 mg/kg/hr, p<0.05) was needed to maintain anesthesia.37 In a study by Klein et al.,38 18 children who underwent 40 elective oncology procedures were randomly assigned to intermittent bolus administration or continuous propofol infusion. Adequate sedation and examiner satisfaction were comparable between the two groups.38 Riphaus et al.39 reported no difference in total propofol dose between the bolus group and the infusion group. Arterial blood pressure <90 mm Hg was documented in two patients in the bolus group and 7 patients in the infusion group (p=0.16).39 Recovery time was significantly shorter in the bolus group compared with the infusion group (19┬▒5 minutes vs. 23┬▒6 minutes, p<0.001) whereas the quality of recovery was identical in the two groups.39

Repeated bolus administration as well as continuous infusion of propofol allow nearly identical good controllability of endoscopic sedation and are associated with similar sedation efficacy and patient's safety. However, the patient's recovery time under continuous sedation is significantly slower and hypotension tends to occur more often. Therefore, repeated bolus administrations of propofol might be more helpful at routine upper endoscopy.

CONCLUSIONS

Currently, both diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy are well tolerated and accepted by both patients and endoscopists due to the implementation of sedation in most clinics worldwide. Accordingly, propofol use is increasing in many countries. It is crucial for endoscopists to be very familiar with the use of propofol or a combination of drugs. However, the controversy regarding the administration of sedation by an endoscopist or an anesthesiologist continues. Until now, there have been no randomized control trials comparing propofol-induced sedation administered by an endoscopist or by an anesthesiologist. It would be difficult to perform this kind of study. Currently, most of sedation drugs are administered during endoscopy by an endoscopist. However, a few death cases are reported every year in Korea. EDP is a trend that cannot be gone against, but proper monitoring and familiarity with the adverse events are needed. For the convenience and safety of sedative endoscopy, it would be important that EDP be generally applied to endoscopic procedures, and for more safety, an anesthesiologist may automatically take care of particular patients at high risk of suffering from propofol side effects.