Duodenal Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphomas: Two Cases and the Evaluation of Endoscopic Ultrasonography

Article information

Abstract

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma mainly arises in the stomach, with fewer than 30% arising in the small intestine. We describe here two cases of primary duodenal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma which were evaluated by endoscopic ultrasonography. A 52-year-old man underwent endoscopy due to abdominal pain, which demonstrated a depressed lesion on duodenal bulb. Endoscopic ultrasonographic finding was hypoechoic lesion invading the submucosa. The other case was a previously healthy 51-year-old man. Endoscopy showed a whitish granular lesion on duodenum third portion. Endoscopic ultrasonography image was similar to the first case, whereas abdominal computed tomography revealed enlargement of multiple lymph nodes. The first case was treated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori, after which the mucosal change and endoscopic ultrasound finding were normalized in 7 months. The second case was treated with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, and rituximab every 3 weeks. After 6 courses of chemotherapy, the patient achieved complete remission.

INTRODUCTION

Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) has been recognized in the early 1980s as a distinct clinicopathological entity.1 MALT lymphoma is defined as an extranodal lymphoma composed of heterogeneous B cells, including small lymphocytes with round nuclei and clumped chromatin (sometimes centrocyte-like), monocytoid cells, and plasmacytoid cells.2 Chin et al.3 described that endoscopic findings associated with gastric MALT lymphoma were divided by four types: superficial, hypertrophic fold, ulceroinfiltrative, and ulcerofungating lesions. Yokoi et al.4 further classified superficial type gastric MALT lymphoma into six types: superficial depressed, submucosal, multiple erosion, cobble-stone-mucosa, partial-fold-swelling, and discoloration types. On the 563basis of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) evaluation, gastric lymphomas can be divided into four types: superficially spreading, diffusely infiltrating, mass forming, and mixed.5 Superficial spreading and diffusely infiltrating types are unique to MALT lymphoma. Mass forming type may represent diffuse large-cell or diffuse mixed-cell type.6 EUS determination of the invasion depth helps to predict a complete response of gastric MALT lymphoma after Helicobacter pylori eradication.7-9

MALT lymphoma of the duodenum is very rare that its characteristic appearance has not been described in detail. In previous reports, endoscopic findings of duodenal MALT lymphoma included disappearance or coarseness of mucosal folds, fold thickening, nodular pattern, ulceration or polyps.10-15 The EUS findings of duodenal MALT lymphoma are not well documented. In the current paper, we describe two cases of duodenal MALT lymphoma which were evaluated by EUS.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

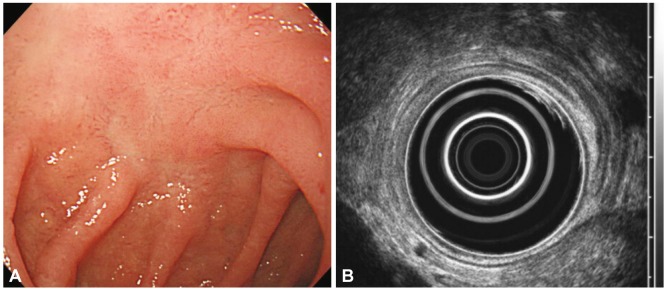

A 52-year-old man visited with right upper quadrant pain. His physical examination, routine hematology, and biochemistry tests were normal. Endoscopy showed a depressed lesion with fold clubbing and granular base on the duodenal bulb (Fig. 1A). EUS showed superficially spreading type hypoechoic lesion showing wall thickening of the second layer and partial indentation of the third layer of the duodenum (Fig. 1B). Histological examination of the stomach was positive for H. pylori. Histology of the duodenal infiltration was compatible with MALT lymphoma: presence of lymphoepithelial lesions with a monoclonal population and positivity for CD20 and bcl-2 and negativity for CD3 and cyclin D1 (Fig. 2). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated no lymph node enlargement. The patient was diagnosed as having stage IE1 MALT lymphoma according to the Ann Arbor classification modified by Musshoff. We decided to eradicate H. pylori with amoxicillin (1,000 mg twice daily), pantoprazol (40 mg twice daily), and clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily) for 2 weeks. At 2 months after the completion of the antibiotic treatment, right upper quadrant pain was subsided and there was no evidence of H. pylori in the gastric mucosa, but endoscopy disclosed no sign of regression of the duodenal lesion. Repeated endoscopy showed regression of the depressed lesion with granular base after 4 months (Fig. 3A). EUS also demonstrated remission of wall thickening 7 months later (Fig. 3B). Histological evaluation noted no lymphoepithelial lesion and immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement, but aggregates of lymphoid cells were persistent. Follow-up abdominal CT scans showed no evidence of lymph node enlargement. The patient was amenable to frequent endoscopies, so we decided to monitor the patient with short-term follow-up endoscopies and biopsies. The most recent endoscopy, 10 months after H. pylori eradication, showed grossly normal mucosa in the duodenal bulb.

Pretreatment endoscopic and ultrasonographic images of case 1. (A) Endoscopic findings. A slightly depressed lesion was seen with fold clubbing and granular base on the duodenum blub (near superior descending angle). (B) Endoscopic ultrasonographic findings. Superficially spreading type hypoechoic lesion was seen with the wall thickening of the second layer and partial indentation of the third layer.

Histopathology of the duodenal lesion of case 1. Lymphoepithelial lesions were seen with diffuse infiltration of small lymphoid cells (H&E stain, ×400).

Case 2

A previously healthy 51-year-old man visited our hospital for a routine check-up. Physical examination and routine hematological and other laboratory studies were normal. Endoscopy showed a whitish granular lesion on duodenum third portion (Fig. 4A). EUS showed superficially spreading and hypoechoic lesion that was similar to the first case (Fig. 4B). Histological examination of the stomach was positive for H. pylori. Histology of the duodenal infiltration was compatible with MALT lymphoma: presence of lymphoepithelial lesions and diffuse infiltration of small lymphoid cells with the monoclonality of immunoglobulin heavy chain and positivity for CD20 (Fig. 5). Chest CT scan showed approximately 0.6-cm sized left supraclavicular lymph node enlargement. Abdominal CT disclosed multiple lymphadenopathy approximately 1 cm in diameter at aortocaval and mesenteric lymph nodes. The patient was classified as having stage IIIE MALT lymphoma, so we administered systemic cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab every 3 weeks. The patient achieved complete remission after six courses of chemotherapy. A follow-up endoscopy after the chemotherapy showed complete regression of the duodenal MALT lymphoma and the enlarged lymph node disappeared on CT scan. The patient was followed up without recurrence for about 6 months.

Endoscopic and ultrasonographic images at the time of the detection of duodenal lesion in case 2. (A) Endoscopic findings. A whitish granular lesion was seen on the duodenum third portion. (B) Endoscopic ultrasonographic findings. Superficially spreading type hypoechoic lesions was seen with the wall thickening of the second layer and partial indentation of the third layer.

DISCUSSION

Primary MALT lymphoma represents approximately 8% of the total number of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The stomach is the most common site of localization, accounting for about one-third of cases.16 Endoscopic findings for MALT lymphoma have been well described in the stomach, in which variable features, including irregular and multiple ulceration, tumor mass, fold thickening, or a combination of these findings suggest the diagnosis of, but are not unique to, gastric MALT lymphoma. In the duodenum, MALT lymphoma is rarely found. None of the endoscopic findings can be specifically related to duodenal MALT lymphoma like gastric MALT lymphoma. Endoscopic findings of previous reports of duodenal MALT lymphoma are divided by three types: ulcerative, polypoid, and superficial type.10-15 Our two cases were classified as the superficial types.

EUS findings for gastric lymphoma can be divided into superficially spreading, diffusely infiltrating, mass forming, and mixed types. Among these, superficial spreading and diffusely infiltrating types are specific to MALT lymphoma. In the superficial spreading type, EUS demonstrated a thickening of the second layer, third layer, or both. In the diffuse infiltrating type, diffuse transmural irregular thickening of the gastric wall was seen. But the most important role of EUS in the management of gastric MALT lymphomas is in staging, which allows choosing appropriate treatment strategies by invasion depth and regional lymph node metastasis evaluation.7-9 The remission rate is highest for mucosa-confined MALT lymphoma (approximately 70% to 90%) and then decreases markedly and progressively for tumors infiltrating the submucosa, the muscularis propria and the serosa.8,9 When the stratification was based on the modified Ann Arbor staging system, the lowest remission rates were reported for advanced stages (≥IIE).17 When comparing the two staging systems, the response rates of the modified Ann Arbor staging IE gastric MALT lymphoma after H. pylori eradication were relatively lower than the rates of T1a (limited to the gastric mucosa) and T1b (invaded beyond superficial mucosa to muscularis mucosa) stage lesions based on TNM.9 Therefore, tumor invasion into submucosal layer should have a lower threshold for referring to alternative treatment modalities, though the current first-line treatment for modified Ann Arbor stage IE and H. pylori positive gastric lymphoma is H. pylori eradication.18

In contrast to gastric MALT lymphoma, EUS findings of duodenal MALT lymphoma have been presented in only a few report. Our two cases of duodenal MALT lymphoma involved submucosal layer. Both were superficially spreading type hypoechoic lesions that showed wall thickening of the second layer and partial indentation of the third layer of the duodenum. This is similar to the superficially spreading type gastric MALT lymphoma.

The optimal treatment of duodenal MALT lymphomas has not been standardized yet. The relationship between duodenal MALT lymphoma and H. pylori has not been established, but the evidence of the efficacy of H. pylori eradication for MALT lymphoma in locations other than the stomach has been shown in the rectum and salivary glands.19,20 In previous six cases of duodenal MALT lymphoma, the authors chose H. pylori eradication as the first-line treatment. Two cases achieved regression of these lesions after the eradication. However, the eradication did not lead to cure in another four cases. Predicting factors of poor response of duodenal MALT lymphoma after eradication are H. pylori negativity, lymph nodes enlargement and invasion depth.10-15 All these cases used the Ann Arbor staging system, which does not accurately describe the depth of infiltration in the duodenal wall. So the difference in response rates between mucosal confined duodenal MALT lymphoma and submucosal invaded lesion after H. pylori eradication could not be evaluated unlike gastric MALT lymphoma. Our first case involving the submucosa and with positivity to H. pylori was treated with a triple therapy. After the eradication of H. pylori, endoscopy and EUS showed regression of the duodenal MALT lymphoma and no immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement. But aggregates of lymphoid cells were persistent. Long-term persistence of monoclonal B cells after histological regression of lymphoma has been reported in about half of gastric MALT lymphoma cases, suggesting that H. pylori eradication suppresses but does not eradicate the lymphoma clones.16 But in long-term follow-ups of some cases with minimal residual disease, neither clinical growth of the lymphoma nor histological transformation was documented despite persistent monoclonality.16 Therefore, we are carefully monitoring recurrence of duodenal MALT lymphoma every 3 to 6 months. In the previous four cases of H. pylori positive stage IE duodenal MALT lymphoma, two patients had regression after the eradication therapy. In our first case, the remission of lymphoma might have been due to the disease invading the submucosa partially and superficially. Deep submucosal invasion could be a prognostic factor for predicting poor response of lymphoma to the triple therapy. In that case, a chemotherapy or radiotherapy should be considered as an alternative treatment. If EUS was performed on the previously reported cases, it could have been useful for predicting the response of lymphoma to H. pylori eradication.

Although more evidence is needed to evaluate the value of EUS, it may be useful to predict a duodenal MALT lymphoma's response to H. pylori eradication. The eradication therapy may be effective for H. pylori positive duodenal MALT lymphoma restricted to the submucosa without lymph node involvement. Regardless of stage, intestinal MALT lymphoma can be controlled relatively well with local or systemic treatments, as is the case with MALT lymphoma at other sites. A triple therapy should be considered as the first-line treatment for these lesions. It is also more cost-effective and tolerable compared to other treatment options (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or operation). However, alternative therapies should be attempted when the patient does not show remission of the disease in 1 year after the eradication therapy likely gastric MALT lymphoma.16 In conclusion, we suggest that EUS should be included as the initial examination to evaluate the invasion depth of H. pylori positive stage IE duodenal MALT lymphoma for choosing the optimal treatment. With more data about EUS findings of these lesions is accumulated, it will lead us to better define disease characteristics and treatment strategy.

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.