Management of Antithrombotic Therapy for Gastroenterological Endoscopy from a Cardio-Cerebrovascular Physician's Point of View

Article information

Abstract

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics for gastroenterological endoscopy is a common clinical issue. To decide how to manage the use of antithrombotics in patients undergoing endoscopy, the risk for hemorrhage and thromboembolism during the procedure must be considered. For low-risk procedures, no adjustments in antithrombotics are needed. For high-risk procedures with a low thromboembolic risk, discontinuation of warfarin at 5 days, and clopidogrel at 5 to 7 days before the procedure has been recommended. However, it is better to continue aspirin use even during high-risk procedures. A heparin bridging therapy may be considered before endoscopy in patients with a high thromboembolic risk. The management of patients taking antithrombotics remains complex, especially in high-risk settings.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, there has been a widespread use of antithrombotics for ischemic strokes and cardiovascular diseases. Many gastroenterologists have had more chances to perform invasive endoscopic procedures on patients taking antithrombotics. Neurologists and cardiologists are also asked to recommend whether gastroenterologists should temporarily stop antithrombotics in patients with previous cerebrovascular diseases or coronary artery diseases during endoscopic procedures. The balance of risks for periprocedural hemorrhage with continuation of antithrombotics versus recurrent thromboembolic events with discontinuation is unclear. Especially, it is not an easy decision when patients with a high thromboembolic risk undergo high-risk endoscopic procedures.

WHAT IS THE PERIPROCEDURAL HEMORRHAGIC RISK OF CONTINUING ANTITHROMBOTICS?

Endoscopic procedures are usually classified into low and high risk according to their potential association with significant hemorrhage. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) proposes that high-risk procedures are those with a rate of hemorrhage of ≥1.5% among patients not taking antithrombotics (Table 1).1,2,3

Diagnostic procedures including biopsy

Diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and sigmoidoscopy including biopsy are considered low-risk procedures. Therefore, regardless of risk for thromboembolic events, the continuous use of antithrombotics including aspirin, clopidogrel, and even warfarin is recommended.2,4

Colonoscopic polypectomy

Postpolypectomy bleeding is the most common complication of colonoscopic polypectomy, occurring in up to 7% of patients.5 Bleeding can occur immediately following polypectomy or be delayed up to 30 days. The ASGE considers colonoscopic polypectomy as a high-risk procedure and recommends stopping aspirin in patients with a low thromboembolic risk or continuing it in patients with a high thromboembolic risk. However, clopidogrel is to be stopped at 7 to 10 days before colonoscopic polypectomy, with aspirin replacement or continuation regardless of thromboembolic risk. The ASGE recommends stopping warfarin before colonoscopic polypectomy.2,4

Endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection

Some patients experience delayed bleeding after endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). The rate of post-ESD bleeding is reported to be 1.7% to 38%.6,7 A recently published guideline recommends stop of aspirin and all other antiplatelet agents before EMR or ESD, in patients with a low thromboembolic risk.4 However, there is no definitive guideline for patients with a high thromboembolic risk.

WHAT IS THE THROMBOEMBOLIC RISK OF TEMPORARILY DISCONTINUING ANTITHROMBOTICS?

Periprocedural stroke risk is increased with discontinuation of antiplatelet medications and anticoagulants. The risk for thromboembolic event with discontinuation of warfarin is probably higher if warfarin is discontinued for ≥7 days (relative risk [RR], 5.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.2 to 24.2). Estimated risk for stroke varies with the duration of stopping aspirin; RR was 1.40 for 5 months, odds ratio was 3.4 for 4 weeks, and RR was 1.97 for 2 weeks.8

Atrial fibrillation, mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism

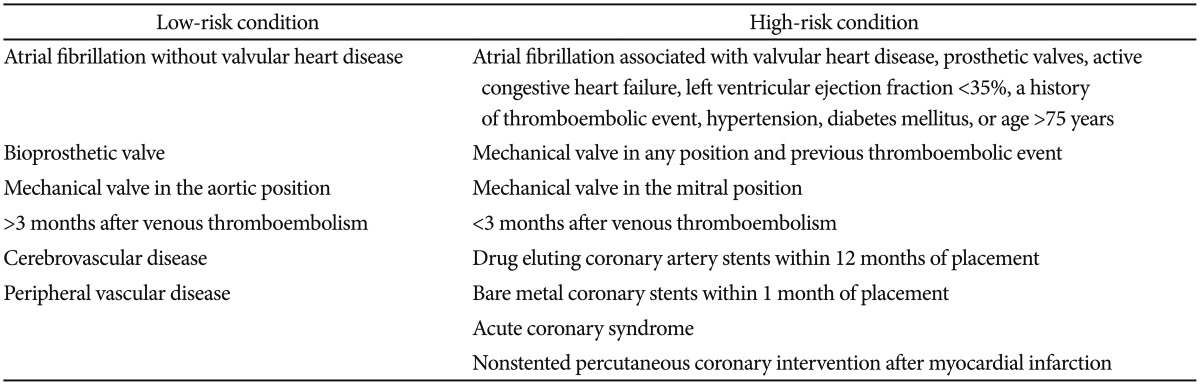

In patients with atrial fibrillation, the CHADS2 score is a significant determinant of the risk for ischemic stroke9 (12.5 to 18.2 stroke rate per 100 patient-year in a score of 5 or 6). Risk for thromboembolic events in patients with mechanical heart valve such as mitral-valve prosthesis, caged-ball or tilting-disk aortic-valve prosthesis, multiple mechanical heart valve is very high (an annual-risk rate of ≥10%).10,11 Risk factors for recurrence in patients with venous thromboembolism are unprovoked venous thromboembolism, severe thrombophilia, active cancer, or venous thromboembolism within previous 3 months (Table 2).2,3 In patients with atrial fibrillation, a mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism at a high thromboembolic risk, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) suggests heparin bridging therapy during interruption of warfarin. However, in patients undergoing a low-risk procedure and taking warfarin, the ACCP suggests continuing warfarin during the procedure.12

Coronary stents

The American Heart Association guidelines recommend uninterrupted dual antiplatelet therapy for at least 1 year in patients with coronary drug-eluting stents.13 Premature stop of dual antiplatelet therapy may lead to stent thrombosis with a mortality rate of ≥50%.12,14,15 The risk for stent thrombosis is highest within 3 to 6 months after the placement of coronary drug-eluting stents.16

In patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy after the placement of drug-eluting stents, when a high-risk procedure is needed, the ACCP recommends deferring the procedure for at least 6 months. However, if a high-risk procedure must be performed within 6 months, dual antiplatelet therapy should be continued. Even if it is difficult to continue dual antiplatelet therapy because of bleeding risk, the patients should take aspirin continuously. For patients undergoing a high-risk procedure after 6 months, continuous use of aspirin and discontinuation of clopidogrel at 5 to 7 days before the procedure is recommended.12

IF WARFARIN IS DISCONTINUED, SHOULD HEPARIN BRIDGING THERAPY BE CONSIDERED?

Heparin bridging therapy aims to minimize the risk for arterial thromboembolism or recurrent venous thrombosis in patients with atrial fibrillation, a mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism. However, heparin bridging therapy is probably associated with an increased risk of periprocedural hemorrhage.

A therapeutic dosage is similar to that used for the treatment of venous thromboembolism (e.g., subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin such as enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice a day or 1.5 mg/kg daily, intravenous unfractionated heparin [UFH] to attain an activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT] 1.5 to 2 times the control aPTT).12 In patients receiving bridging therapy with therapeutic-dose UFH, the ACCP suggests stopping UFH 4 to 6 hours before the procedure. In patients receiving bridging therapy with therapeutic-dose enoxaparin, the ACCP suggests administering 50% of the total daily enoxaparin dose approximately 24 hours before the procedure.12

IF ANTITHROMBOTICS ARE DISCONTINUED, WHAT SHOULD BE THE TIMING OF STOP?

Most patients have an international normalized ratio of ≤1.5 approximately 5 days after stopping warfarin.17,18,19 In patients who require temporary discontinuation of warfarin, the ACCP recommends stopping warfarin approximately 5 days before the procedure and resuming warfarin approximately 12 to 24 hours after the procedure (evening or next morning) and when there is adequate hemostasis.

Cilostazol has known to have a less bleeding tendency. Antithrombotic effect of cilostazol tends to disappear roughly 2 days after discontinuation.20 For patients taking clopidogrel at a low risk for cardiocerebrovascular events, the ACCP suggests stopping clopidogrel 5 to 7 days before a high-risk procedure.12

The restart of antithrombotic therapy is a major determinant of the hemorrhagic risk after invasive procedures. In patients receiving heparin bridging therapy, heparin at a therapeutic dose should be withheld for 48 hours after the procedure. Aspirin or clopidogrel can be reinitiated within 24 hours after the procedure.

KEYS TO SUCCESSFUL MANAGEMENT OF ANTITHROMBOTICS IN THE PERIPROCEDURAL PERIOD

1) Communication between patient and care providers, including the proceduralist.

2) Advanced preprocedural planning to allow for medication adjustments and patient counseling.

3) Assessment of the hemorrhagic risk during procedures if antithrombotics are continued.

4) Assessment of the thromboembolic risk if antithrombotics are temporarily stopped.

5) Involving patients in the decision making about anticoagulation interruption and bridging with risk for thromboembolism or hemorrhage, especially in areas of uncertainty.

6) Avoiding premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary stents.

7) Conservative discontinuation and reinitiation of anticoagulation therapy to prevent postprocedural bleeding.21

CONCLUSIONS

Periprocedural management of antithrombotics depends on risk assessment for hemorrhage and thromboembolism. For patients taking antithrombotics for a long time, periprocedural management of antithrombotics for gastroenterological endoscopy needs to be individualized. It is best for the gastroenterologist to seek advice from the neurologist or cardiologist to assess the patient's risk for thromboembolism. The patients should know better than anyone about the risk and benefit of endoscopic procedures, and should be informed in advance of early signs of hemorrhage after the procedures.

Notes

The author has no financial conflicts of interest.