Multicentric Type 3 Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumors

Article information

Abstract

A 50-year-old woman with incidentally detected multiple gastric polyps and biopsy-proven neuroendocrine tumor (NET) was referred to our hospital. More than 10 polypoid lesions (less than 15 mm) with normal gastric mucosa were detected from the gastric body to the fundus. The serum level of gastrin was within the normal limits. There was no evidence of atrophic changes on endoscopy and serologic marker as pepsinogen I/II ratio. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed no evidence of metastatic lesions. She refused surgery, and we performed endoscopic polypectomy for almost all the gastric polyps that were greater than 5 mm. Although the histological examination revealed that all the removed polys were diagnosed as NET G1, three of them extended to the lateral or vertical resection margins, while two exhibited lymphovascular invasion. A follow-up upper endoscopy that was performed 6 months after the diagnosis showed multiple remnant gastric polyps that were suggestive of remnant gastric NET.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), previously referred to as gastric carcinoids, are rare neoplasms that account for 0.6% to 2% of all identified gastric polyps and 8.7% of all gastrointestinal NETs.12 The incidence of gastric NETs has increased over the last 50 years, partly due to the improvement of endoscopic surveillance and heightened awareness.13

Gastric NETs are usually classified into three types based on the background gastric pathology. Type 1 arises in the presence of achlorhydric atrophic body gastritis (ABG), type 2 is associated with the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1), while type 3 includes the "sporadic" NET in the absence of a specific background of pathologic changes.4 This classification plays an important clinical role when approaching a gastric NET, not only due to the possible coexistence of a predisposing condition such as ABG and ZES, but also due to the implications in tumor behavior and the prognosis of the patient.

Type 3 gastric NET represents 14% to 25% of gastric NETs and have poor prognosis with the highest rate of distant metastasis.56 They mostly are large (>2 cm) solitary lesions arising in the normal surrounding mucosa.7 In this case, we describe a patient with multicentric (more than 10) small gastric NETs identified as type 3.

CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old woman underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for a health check-up. More than 10 polypoid lesions of the stomach were discovered, and the biopsy specimens from the gastric polyps demonstrated grade 1 (G1) NET, according to World health Organization classification.8 She was referred to our hospital for proper management of the gastric NETs.

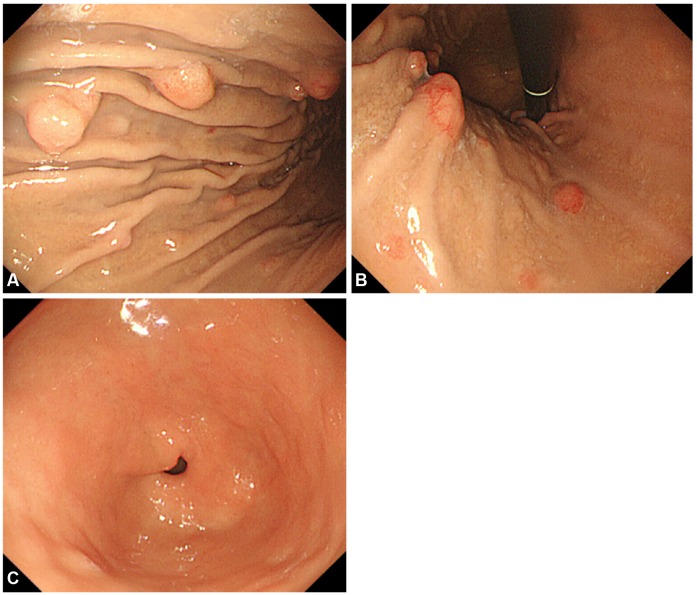

She had no carcinoid symptoms such as flushes or diarrhea, had no significant medical history, and did not previously receive any proton pump inhibitors or H2 receptor antagonists. Interestingly, her sister also had gastric NETs. The results of the peripheral blood and routine chemistry tests were within the normal limits. The serum level of fasting gastrin was 85.2 pg/mL (normal rage, 0 to 90). The serum level of pepsinogen I (PG I) was 70.7 ng/mL and that of pepsinogen II (PG II) was 10.9 ng/mL with the PG I/II ratio being 6.48 (positive range, PG I ≤70 ng/mL and PG I/II ≤3.0 ratio). Helicobacter pylori were not detected with rapid urease test and anti-H. pylori immunoglobulin G antibody level was 9.1 AU/mL with equivocal range (negative range, <8.0 AU/mL). On EGD (A5 CE0 mode, GIF-Q260 scope; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan), multiple polypoid lesions were detected mainly around the greater curvature of the gastric body to the fundus. Some polyps accompanied the erythematous mucosal change, and the maximum diameter of polyps was less than 15 mm (Fig. 1A, B). Focal granular mucosal change was detected in the gastric body, but there was no evidence of atrophic gastritis in the antrum (Fig. 1C). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed multiple enhancing polypoid lesions in the stomach without any evidence of metastatic lesions.

Endoscopic findings. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed multiple polypoid lesions (less than 15 mm) located on lower body to fundus of stomach with normal gastric mucosa (A, B). There was no evidence of atrophic gastritis in the antrum (C).

She refused surgery, and we decided to perform endoscopic polypectomy. Polypectomy was performed without complications and almost all the gastric polyps that were greater than 5 mm in size were removed. A histological examination revealed that all the removed polys were NET GI, which was composed of uniform cells with round or ovoid nuclei and scanty eosinophilic cytoplasm, proliferating in a trabecular or glandular pattern (Fig. 2). The tumor cells invaded the submucosal layer, diffusely staining for chromogranin A. The mitotic count was absent and the Ki-67 index was less than 1%. Most significantly, three of the polyps extended to the lateral or vertical resection margins and two exhibited lymphovascular invasion. Fundic gland atrophy was not detected from random biopsies on the greater curvature of the upper body, mid-body, and antrum. We diagnosed this patient with multicentric type 3 gastric NETs. After the procedure, she still refused surgery despite the high risk of metastasis and tumor-related death. Follow-up EGD at 6 months after diagnosis showed multiple remnant gastric polyps suggestive of gastric NETs (Fig. 3).

Histological examination of the gastric neuroendocrine tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E stain) showed that tumor cells invaded into the submucosal layer (A, ×40). The tumor was composed of uniform cells with round or ovoid nuclei and scanty eosinopohlic cytoplasm, proliferating in a trabecular or glandular pattern, which were absent of mitotic count (B, ×100). Immunohistochemical stating for chromogranin A was diffusely positive (C, ×40). The Ki-67 labeling index was less than 1% (D, ×100).

DISCUSSION

Gastric NETs were first categorized into three types in 1993 by Rindi et al.4 Type 1 and 2 are related to the presence of hypergastrinemia causing hyperplasia of the precursor enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells, whereas type 3 occurs sporadically and independently of gastrin.4 This classification is based on the clinical differences of epidemiological, pathophysiological, endoscopic, and histological features between each type that affects prognosis, management, and follow-up.9 Type 1 and 2 gastric NET have indolent behaviors, but type 3 gastric NET may be life-threatening with a high risk of metastasis and tumor-related death.7

In type 1 and 2 gastric NET, hypergastrinemia plays a crucial role in the development of tumors.10 The ECL cells, located in the corpus-fundus mucosa of the stomach, represent the major proliferative target of gastrin. Proliferation of the ECL cells results in tumorigenesis of NET. Gastric NET arising from these conditions grows usually multicentric lesions. On the other hand, types 3 gastric NETs are "gastrin-independent" tumors that are rarely multiple.4

Endoscopically, type 1 gastric NET tumors are often found in the fundus of stomach and are mostly polypoid (78%), of small shape (size 5 to 8 mm), and are multicentric (68%; mean number, 3).1112 Type 2 gastric NETs are also usually identified as small, often multiple, polypoid tumors (<1 cm in size) in fundus.13 On the contrary, a type 3 gastric NET is typically a large (>1 cm, 66%), solitary (96%) lesion, that grows from the gastric body/fundus, and occurs in the antrum, within the context of a normal gastric mucosa.1415 In this case, the endoscopic findings of multicentric (>10 lesions), small (<2 cm) polypoid lesions in the gastric fundus resembled closely to the type 1 and 2 gastric NETs. However, the diagnosis of type 3 gastric NET was clinically based on normal gastrin levels and the absence of evidence of gastric atrophy or significant peptic ulcers that are commonly seen with type 1 or 2 gastric NETs, respectively.

A few cases of multiple gastric NETs without hypergastrinemia have been reported. Some cases of multiple gastric NETs in MEN 1 patients without hypergastrinemia have been previously described.161718 These cases suggest that the development of gastric NET in MEN 1 patients arises not only from hypergastrinemia in ZES, but also from the genetic mutations of the MEN 1 gene, one of the tumor suppressor genes. Moriyama et al.19 first reported multicentric gastric NETs that have been classified as type 3. In this case, the patient concomitantly had a pituitary tumor, an adenomatous goiter, and bilateral Warthin's tumors. Although a possible predisposition to MEN 1 is suspected, genetic mutations could not be found in all the exons of the MEN 1 gene that has been translated. To our knowledge, this is the second report of a multicentric type 3 gastric NET. More aggressive characteristics, including lymphovascular invasion, were observed in our case.

Type 3 gastric NETs exhibit a more aggressive course than the type 1 and 2 gastric NETs. Most type 3 gastric NETs showed lymphovascular and deep wall invasion at the time of diagnosis.20 In other cases, 60% to 75% present with metastatic disease, and tumor-related death occurs 28 months after diagnosis in 25% to 30% of cases.420 Thus, the therapeutic approach to type 3 gastric NETs should be managed surgically.9 Only small (<10 mm), well differentiated (G1) type 3 gastric NETs limited to the submucosal layer have been treated efficaciously by endoscopic mucosectomy, in a retrospective analysis.15

In summary, we described the case of a 50-year-old woman with multicentric type 3 gastric NET without hypergastrinemia, which was endoscopically similar to the type 1 and 2 lesions but with more aggressive features, such as lymphovascular invasion. It will be necessary to study various other cases in order to discover the pathogenesis, and develop therapeutic strategies. This case serves as a reminder to gastroenterologists who encounter NET cases in their clinical practice, that even if the NET is multiple, a diagnosis of type 3 NET should be considered so that a careful evaluation of atrophic status such as endoscopic findings, serologic biomarkers, and gastrin levels can be conducted.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my very great appreciation to Dr. Lee, my supervisor, for his valuable and constructive suggestions during the planning and preparing of this case report.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.