Endoscopic Suturing for the Prevention and Treatment of Complications Associated with Endoscopic Mucosal Resection of Large Duodenal Adenomas

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is the primary treatment for duodenal adenomas; however, it is associated with a high risk of perforation and bleeding, especially with larger lesions. The goal of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility and safety of endoscopic suturing (ES) for the closure of mucosal defects after duodenal EMR.

Methods

Consecutive adult patients who underwent ES of large mucosal defects after EMR of large (>2 cm) duodenal adenomas were retrospectively enrolled. The OverStitch ES system was employed for closing mucosal defects after EMR. Clinical outcomes and complications, including delayed bleeding and perforation, were documented.

Results

During the study period, ES of mucosal defects was performed in seven patients in eight sessions (six for prophylaxis and two for the treatment of perforation). All ES sessions were technically successful. No early or delayed post-EMR bleeding was recorded. In addition, no clinically obvious duodenal stricture or recurrence was encountered on endoscopic follow-up evaluation, and no patients required subsequent surgical intervention.

Conclusions

ES for the prevention and treatment of duodenal perforation after EMR is technically feasible, safe, and effective. ES should be considered an option for preventing or treating perforations associated with EMR of large duodenal adenomas.

INTRODUCTION

Duodenal adenomas are uncommon lesions with a reported prevalence of 0.3% to 4.6%, often incidentally found in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy [1-4]. Approximately 40% of duodenal adenomas are sporadic, and the remaining 60% are found in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis [5,6]. The standard treatment for a solitary duodenal adenoma is endoscopic polypectomy, which includes endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) [7,8]. However, advanced technical expertise is required to safely perform ESD, which has limited its widespread use [9]. Indeed, the difficulty of ESD stems from the anatomical features of the duodenum, with increased vascularity in the submucosal layer and a thin muscularis propria, posing substantial risks of complications such as bleeding and perforation [10]. Consequently, EMR is more commonly employed in Western countries [9,11].

Although EMR of duodenal lesions can often achieve favorable en bloc resection rates, it is still associated with a high risk of perforation and bleeding, with potentially devastating consequences [11]. Delayed perforation has been reported in 1% of non-ampullary adenomas treated with EMR; however, it could be significantly more frequent after the endoscopic resection of large-sized adenomas [12,13]. Patients with perforation are typically referred for emergent surgery, although it may still result in significant mortality and morbidity [12,14,15]. Closure of submucosal defects in the duodenum has been shown to decrease the number of delayed adverse events associated with submucosal dissection [16]. The OverStitch endoscopic suturing (ES) system (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX, USA), currently the only suturing device commercially available in the United States, is specifically designed for tissue approximation and allows the creation of either continuous running or interrupted stitches [17]. The device has been shown to reliably appose tissues and to close perforations throughout the gastrointestinal tract [16]. It has been employed for closing persistent gastrocutaneous fistula or active ulcers, and for fixing esophageal stents [18-20]. However, the application of ES with the OverStitch system to prevent or treat duodenal perforations associated with duodenal EMR has not been well studied.

Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the technical feasibility, safety, and outcomes of ES for the closure of mucosal defects resulting from duodenal EMR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

This was a retrospective study of consecutive adult patients who underwent ES of large mucosal defects after EMR at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center over a 9-month period (March 2019–November 2019). Patients with benign duodenal mucosal adenomas of at least 20 mm in size, who were treated with EMR followed by attempted closure with ES, were considered eligible for inclusion in this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (approval no. 00000346, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

Endoscopic mucosal resection and suturing

EMRs were performed by a single endoscopist (SKL), and the procedures were performed under monitored anesthesia care. After the submucosal injection of a mixture of epinephrine (dilution 1:10,000), methylene blue, and normal saline, EMR was performed using a single-use, braided snare (K-001; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA, USA). Hot forceps (HDBF-2.4SN-230-S; Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) was used to ablate tissue that could not be captured with the EMR snare. A forward-viewing gastroscope, pediatric colonoscope, or side-viewing duodenoscope was used at the discretion of the endoscopist. After the completion of EMR, ES was performed with a double-channel endoscope (GIF 2T-180; Olympus America) preloaded with an OverStitch ES device, orally inserted to the location of the EMR. The post-EMR mucosal defect was closed using interrupted stitches, with the primary intention of visibly closing the entire EMR resection defect. For each suture, the distal end of the mucosa was first captured and the proximal end was subsequently captured before cinching. Each suture was placed perpendicular to the duodenal folds to decrease the risk of duodenal luminal narrowing. Patients were discharged on the same day after the procedure, unless periprocedural complications occurred. All intraoperative and postprocedural clinical events were managed according to the standard of care and recorded, including those reported during a telephone visit performed on days 7–14.

Data collection and analysis

The patients’ demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, pathologic diagnosis, lesion size, location, procedure outcomes, adverse events, and follow-up outcomes were reviewed. The collected data were stored in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Co., Redmond, WA, USA). Data are reported as means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and as percentages for nominal variables. The primary study outcomes (delayed bleeding and perforation) were quantified.

RESULTS

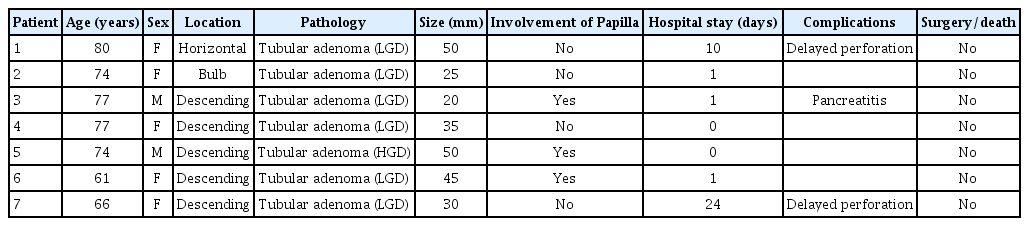

During the study period, ES of mucosal defects was performed in seven patients in eight sessions (Table 1). Of the eight sessions, six were performed for prophylaxis and two for perforation (at 3 and 14 hours after EMR). All patients were referred from outside hospitals. The mean age of the patients was 72.7±11.7 years. The patients in this case series included five women and two men, of whom six were Caucasian and one was Asian. Two patients underwent prior duodenal EMR procedures. All lesions were removed with EMR, and the mean lesion size was 35.7±15.7 mm × 2.1±1.1 mm. The location of the lesions included the duodenal bulb (n=1), descending duodenum (n=5), and horizontal duodenum (D2–D3 junction; n=1). Histopathologic evaluation of the resected lesions revealed tubular adenoma (TA) with low-grade dysplasia (n=6) and TA with high-grade dysplasia (n=1).

All ES sessions were technically successful, although one stitch in a prophylactic case was intraprocedurally noted to be loose (Fig. 1). The location of the stitch was complicated by a delayed perforation; however, it was completely closed in another ES session without further adverse events or interventions (Fig. 1). The average number of stitches per case was 3.3±0.7. In four prophylactic cases, clips were initially applied but were deemed unsuccessful or inadequate before the ES approach was employed (Fig. 2). Five patients with uncomplicated ES were discharged immediately after the procedure. Adverse events were noted in two patients. A single episode of postprocedural pancreatitis was noted that required 1 day of hospitalization for observation. Overall, no early or delayed post-EMR bleeding was recorded. In addition, no clinically obvious duodenal stricture or recurrence was encountered on endoscopic follow-up evaluation, and no patients required subsequent surgical intervention.

(A) A 30-mm duodenal adenoma located in the junction of the second and third duodenum. (B) After duodenal endoscopic mucosal resection, prophylactic OverStitch endoscopic suturing was performed. (C) One of the three sutures was loose, and duodenal perforation was observed 5 hours later. (D) The second OverStitch endoscopic suturing was performed. (E) The perforation site was closed using three separate OverStitch endoscopic stitches. (F) Fluoroscopy showed no dye leakage through the duodenum.

(A) A 20-mm duodenal adenoma located in the anterior wall of the second part of the duodenum. (B) After duodenal endoscopic mucosal resection. (C) Prophylactic closure was first attempted through endoscopic clip application; however, it failed owing to a large diastasis between the edges and the tangential application. OverStitch endoscopic suturing was then performed with interrupted stitches. (D) The closure of the defect with OverStitch endoscopic suturing.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first case series focusing on the use of the OverStitch ES device for post-EMR duodenal mucosal defects after the resection of large duodenal mucosal lesions. We demonstrated that prophylactic complete closure of a duodenal mucosal defect is technically feasible. Even duodenal perforations, if discovered early, may be effectively closed with OverStitch ES without the typically difficult and prolonged course. In fact, none of the patients in our small case series required surgical interventions. Our results support the notion that, by apposing the mucosectomy-induced cut edges over a large area together, ES can decrease the risk of delayed perforation. Thus, we have demonstrated an approach for an early and reliable closure of a perforation, which minimizes spillage of food contents and the pro-inflammatory pancreaticobiliary fluid, thereby facilitating recovery and shortening the hospital stay.

Duodenal neoplasms are uncommon, and primary duodenal adenocarcinoma represents only 0.3% of all malignant neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract [3,4]. Approximately 40% of duodenal adenomas are sporadic, and the remaining 60% are found in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis [5,6]. Although there is no definitively established treatment for large duodenal adenomas, EMR is generally considered the first-line treatment for duodenal neoplasms [21,22]. However, performing duodenal EMR is challenging for multiple reasons. First, the tortuous and narrow lumen poses major difficulty in obtaining a full view of the lesion in a stable position. Second, Brunner’s glands in the submucosal layer can stiffen the duodenal wall, making submucosal lifting difficult to achieve. Third, the thinness of the duodenal wall is a predisposing factor for mucosectomy-related perforation [21,22]. Fourth, exposure of the abundant submucosal duodenal vasculature during EMR increases the risk of postprocedural bleeding. In addition, constant bathing of the postmucosectomy tissue with bile fluid, gastric acid, and pancreatic juice likely predisposes patients to a considerable risk of perforation of the thinned wall.

Delayed perforation has been reported in 1% of non-ampullary adenomas; however, it may be significantly more frequent after the endoscopic resection of large-sized adenomas [12,13]. Patients with perforation are typically referred for emergency surgery, although it will still result in significant mortality and morbidity [12,14,15]. The OverStitch ES system is currently the only commercially available, Food and Drug Administration-approved ES device in the United States [23-26]. It is possible to perform ES to prevent or treat complications associated with duodenal EMR. The literature on the application of ES during duodenal EMR is scarce. Almost all previously described techniques for the closure of post-EMR or post-ESD defects were performed with endoscopic clips, sometimes in combination with endoscopic loops [26-30]. Clipping, when performed in combination with an endoscopic loop, may be technically challenging or even impossible to accomplish. Besides the obvious difficulty in pulling together the edges of a large duodenal mucosal defect, standard two-arm clips are challenging to orient and to use for capturing tissue in a tangential manner. When placed parallel to the horizontal folds, they risk the creation of duodenal strictures. Over-the-scope clips are easier to deploy than hemostatic clips, and are highly secure and reliable when the defect is perfectly captured. However, they are only suitable for treating tissues <1.5 cm in diameter, and precise deployment is absolutely essential. Additionally, they must be properly oriented to prevent stricture formation. A recent report by Fukuhara et al. proposed a multidisciplinary endoscopic approach for managing duodenal perforations [31]. The authors used a combination of clips, polyglycolic acid sheets, fibrin glue, and endoscopic nasobiliary and pancreatic duct drainage tube insertion. This method utilizes very complicated maneuvers, and its true efficacy warrants further validation.

The OverStitch suture device used in this study was attached to the tip of a double-lumen upper endoscope. Its mobile, curved arm was used to transfer a short needle that carries a suture through the length of one of the instrument channels. With the opening and closing of this arm, the needle was passed back and forth through a targeted tissue, thereby running the stitches through it. The advantage of using this device for closing a duodenal defect is that capturing one of the edges is an independent action from grasping the opposite edge, which is technically much easier to perform than clip placement. Furthermore, placement of the needle on the tissue does not require the precision necessary for clipping. The thread may land on the tissue farther away from the edge, which is healthier and can more strongly hold it in place. Finally, coaxial stitching is relatively easy to perform, thereby reducing the chance of stricture formation to a minimum.

The main limitations of our study were the retrospective, single-center design and the small number of patients. However, our consecutive enrollment of patients who underwent duodenal endoscopic resection was expected to reduce possible selection bias. Moreover, because all procedures were performed by a single skilled endoscopist who has performed a large volume of ES procedures, generalizing our experience to other centers or providers may not be appropriate. In addition, no suturing was performed beyond the D2–D3 junction, which might have been extremely challenging. Large prospective multicenter studies are needed to confirm our preliminary results.

The size of duodenal lesion resection for which ES can be safely performed remains to be determined. However, given the craniocaudal nature of endoscopic sutures, we believe that this technique is feasible for lesions measuring approximately 5 cm in length. For the same reason, there should be no limitation on the circumferential size of the lesion.

In conclusion, ES for the prevention and treatment of duodenal perforations after EMR is technically feasible, safe, and effective. ES can be considered an option for the prevention and treatment of perforations associated with EMR of large duodenal adenomas.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Simon K. Lo

Data curation: Jaeil Chung, Kelly Wang, Alexander Podboy

Writing-original draft: JC, SKL

Writing-review&editing: JC, KW, AP, Srinivas Gaddam, SKL