See commentary "Clinicians should be aware of proton pump inhibitorŌĆōrelated changes in the gastric mucosa" in Volume 57 on page 51 AbstractBackground/AimsMultiple white and flat elevated lesions (MWFL) that develop from the gastric corpus to the fornix may be strongly associated with oral antacid intake. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the association between the occurrence of MWFL and oral proton pump inhibitor (PPI) intake and clarify the endoscopic and clinicopathological characteristics of MWFL.

MethodsThe study included 163 patients. The history of oral drug intake was collected, and serum gastrin levels and anti-Helicobacter pylori immunoglobulin G antibody titers were measured. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. The primary study endpoint was the association between MWFL and oral PPI intake.

ResultsIn the univariate analyses, MWFL were observed in 35 (49.3%) of 71 patients who received oral PPIs and 10 (10.9%) of 92 patients who did not receive oral PPIs. The occurrence of MWFL was significantly higher among patients who received PPIs than in those who did not (p<0.001). Moreover, the occurrence of MWFL was significantly higher in patients with hypergastrinemia (p=0.005). In the multivariate analyses, oral PPI intake was the only significant independent factor associated with the presence of MWFL (p=0.001; odds ratio, 5.78; 95% confidence interval, 2.06ŌĆō16.2).

INTRODUCTIONNon-neoplastic protruding epithelial lesions in the stomach are primarily fundic gland polyps and foveolar-hyperplastic polyps.1 Nevertheless, Kawaguchi et al.,2 at an academic meeting in 2007, first reported that multiple non-neoplastic epithelial protruding lesions (i.e., multiple white and flat protruding lesions) could occur from the gastric corpus to the fornix. In 2011, Kamada et al.3 named these lesions multiple white and flat elevated lesions (MWFL) and described them at an international academic conference for the first time. MWFL were frequently observed in patients who received antacids (proton pump inhibitors [PPIs] or H2 receptor antagonists) for an extended period.3 We also reported a retrospective observational study whose findings indicated a possible association between the presence of MWFL and a history of antacid use,4 suggesting that MWFL occurrence is associated with PPI use.

MWFL are endoscopically characterized by a whitish color with flat protrusions of various sizes, serrated borders, and regular tubular patterns on the surface.5 The lesions are easily visible through non-magnifying observation using narrow-band imaging (NBI).4 Moreover, the histopathological findings of MWFL are characterized by hyperplastic changes in the foveolar epithelium of the fundic gland mucosa.2,6

In addition, oral PPIs reportedly increase the number and size of fundic gland polyps,7,8 which exhibit edematous swelling with a multilocular morphology.9 Furthermore, the number of foveolar-hyperplastic polyps may increase due to oral PPI-as┬Łsociated hypergastrinemia.8,10 The histopathological findings of patients with fundic gland polyps, foveolar-hyperplastic polyps, and PPI-associated polyps differ from those with MWFL due to long-term oral intake of PPIs.11 A report on malignant transformation from polyps, similar to PPI-associated polyps, is also available.12

With an aging population and changing disease structures, the frequency of PPI use is expected to increase, and the incidence of PPI-associated non-neoplastic epithelial protruding lesions in the stomach is expected to increase. However, prospective studies are lacking on the association between MWFL occurrence and oral PPI intake that also include patient characteristics and histopathological findings. Thus, this prospective observational study aimed to determine the association between MWFL occurrence and PPI intake and to clarify the endoscopic and clinicopathological characteristics of MWFL.

METHODSStudy designThis single-center prospective observational study was designed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample sizeThe necessary number of patients was calculated based on a pilot study conducted before this study. The oral administration arm was defined as the group that received oral PPIs and presented with MWFL. The non-administration arm was defined as the group that did not receive oral PPIs and presented with MWFL with an incidence of 18% in the oral administration arm and 4.3% in the non-administration arm. At a significance level (two-sided ╬▒) of 0.05, the power was 80%, and the 1ŌĆō╬▓ was 0.8. Based on these data, the necessary number of patients calculated using the sample size for comparing two proportions was 162. Based on a screen failure rate of approximately 20% to 25% of the enrolled patients in the pilot study, the necessary number of patients was 300. If the interim analysis showed a significant difference in the primary endpoint, the study was terminated for ethical reasons.

Study populationPatients who met all the inclusion criteria and did not meet any exclusion criteria were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) scheduled to undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy using magnifying endoscopy; and (2) aged Ōēź20 years and provided written informed consent to participate. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) at high risk of bleeding when undergoing biopsies, including taking oral antithrombotic agents; (2) presence of lesions, including erosions, ulcerations, or hemorrhage, where there was difficulty observing the lesion surface; (3) presence of underlying diseases associated with bleeding tendencies, such as liver cirrhosis, hemophilia, and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; (4) having undergone total or partial gastrectomy; (5) concurrent psychiatric illnesses or symptoms that could make participation in the study difficult; and (6) considered inappropriate for participating in this study by the principal investigator or sub-investigator.

Protocol testingFor patients scheduled to undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, informed consent for this study was obtained using an informed consent form prior to treatment. Before endoscopy, patients were asked about their current and past oral medications, and serum gastrin and anti-Helicobacter pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody titers were measured. Endoscopy was performed by a specialist from the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society or a physician with equivalent knowledge and skills and at least 2 years of experience performing magnifying endoscopy using NBI.

The endoscope was a high-resolution magnifying upper gastrointestinal endoscope (GIF-H290Z; Olympus Co., Ltd.). An endoscopy system (Evis Lucera Elite; Olympus Co., Ltd.) was used. In addition, a soft black hood (MAJ 1989; Olympus Co., Ltd.) was attached to the distal end of the endoscope to maintain a constant focal distance between the mucosal surface and endoscope tip during magnification endoscopy at maximum magnification. Patients were given water (100 mL) containing 1,000 units of pronase (Kaken Pharmaceutical), 1 g of sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mL of dimethylpolysiloxane (20 mg/mL; Hori Pharmaceutical Ind.) 30 minutes before the endoscopic procedure.

After scope insertion, the entire gastric mucosa was examined using a systematic screening protocol for the stomach.13 All endoscopic images were recorded using an image-filing system (Solemio Quev; Olympus Co., Ltd.). In addition, for gastric polyps, standard observation images, images after applying the indigo carmine dye, non-magnified images using NBI, and magnified images using NBI were obtained. Observation conditions with magnifying endoscopes were set as color mode 1 for narrow-band light observation and B8 structural enhancement. In patients with polyps, biopsies were performed using specimens collected from the polyp and the mucosa of the lesser curvature of the gastric corpus where no polyps were present. For patients without polyps, biopsy samples were obtained from the lesser curvature of the gastric corpus. For the different types of polyps (macroscopic type), each was subjected to magnified observation using NBI and biopsy. If multiple lesions were observed, the largest lesion was subjected to magnified examination using NBI and biopsy.

Histopathological assessmentsAll of the biopsied specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed of 4-┬Ąm-thick sections. The H&E-stained specimens were microscopically examined by a pathologist (S.N.) who was blinded to the endoscopic findings, and the histopathological characteristics were determined. Specifically, the presence or absence of foveolar hyperplasia and intestinal metaplasia in the polyps and surrounding mucosa and the presence or absence of parietal cell protrusion and oxyntic gland dilatation in the surrounding mucosa were evaluated.

Assessment of atrophic mucosaAtrophy of the surrounding mucosa was assessed through endoscopic observation using white light according to the Kimura and Takemoto classification.14 Moreover, in the present study, atrophy was defined as the presence of whitish mucosa with transillumination of blood vessels in the lesser curvature of the stomach. In contrast, the absence of atrophy was defined as the absence of these findings.

Assessment of H. pylori infectionThe diagnosis of H. pylori infection depended on the serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody titers and microscopic examination of the biopsy specimens. If serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody titers and microscopic examination yielded positive results, the patient was judged to have a currently active H. pylori infection. If the serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody titers and microscopy results were negative, there was no history of eradication, and there were characteristic endoscopic findings of an H. pylori uninfected stomach, a patient was judged not to be infected with H. pylori, whereas a patient was assessed as having been previously infected with H. pylori if there was a history of eradication or endoscopic atrophy.

EndpointsThe primary endpoint was the association between MWFL and oral PPI intake. The secondary endpoints included the endoscopic and histopathological characteristics of MWFL, and the association of the presence of MWFL with each age/sex, the presence of fundic gland or foveolar-hyperplastic polyps, hypergastrinemia, H. pylori infection status, and gastric mucosal atrophy.

Statistical analysisFor statistical analysis, Fisher exact test was performed to compare the proportions of categorical variables between the two arms. Student t-test was performed to compare the means of continuous variables between the two arms. Logistic regression analysis was performed to calculate covariate-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In both evaluations, values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 21.0 for Windows (IBM Corp.).

RESULTSOf the 168 patients who provided informed consent, 163 were included in the analyses, excluding two who underwent partial gastrectomy and three without biopsies of the polyps. MWFL were observed in 45 of the 163 patients (27.6%).

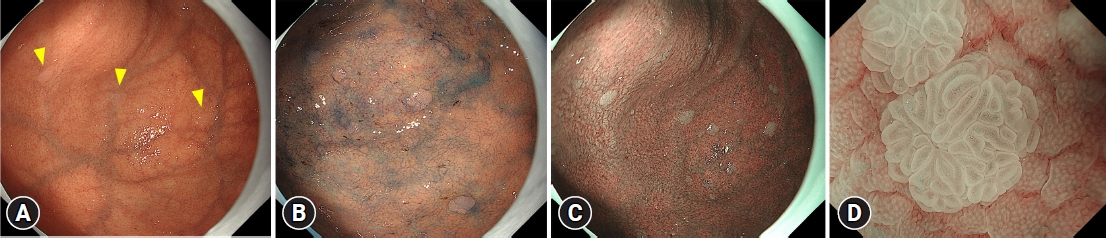

The endoscopic features of MWFL using standard observation with white light revealed multiple flat elevated lesions of various sizes and white tones in the gastric fundus and corpus (Fig. 1A). The boundary between each lesion and the surrounding mucosa was clear. Observations after indigo carmine dye application showed flat protrusions with smooth surfaces that repelled the dye (Fig. 1B). Observation without magnification using NBI revealed a brownish color in the surrounding mucosa. The contrast between the white and flat elevated lesions was increased, and the lesions were more easily visible compared to standard observation with white light (Fig. 1C).

The features of the magnified image obtained using NBI (Fig. 1D) included clear demarcation lines at the base of the flat elevated lesions and not-observed microvascular patterns in the superficial layer of the lesion. Regarding the microsurface patterns, the individual marginal crypt epithelial morphology was elongated and oval, and their shapes were uniform. The marginal crypt epithelium was wider than the surrounding mucosa, and the intervening parts between the crypts were slightly wider and brownish in color.

Age, sex, oral PPI intake rate (Supplementary Table 1), presence or absence of fundic gland polyps and foveolar-hyperplastic polyps, hypergastrinemia (Ōēź400 pg/mL), atrophy in the surrounding gastric mucosa, and the H. pylori infection status of patients with or without MWFL are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the 45 patients with MWFL (21 men, 24 women) was 70.4 years. The mean age of the 118 patients without MWFL (59 men, 61 women) was 66.0 years. The mean age and sex of the patients with versus without MWFL were compared, and patients with MWFL were significantly older. Oral PPIs were used in 35 (77.8%) of 45 patients with MWFL and 36 (30.5%) of 118 patients without MWFL. Patients with MWFL had a significantly higher rate of PPI use than those without MWFL (p<0.001). Additionally, hypergastrinemia was observed in 37.8% (17/45) of the patients with MWFL and 16.1% (19/118) of those without MWFL. A significant association was observed between MWFL and hypergastrinemia in the majority of patients (p=0.005). Regarding H. pylori infection status, none of the patients with MWFL had active H. pylori infection. No significant differences were observed in the presence or absence of other fundic gland polyps, foveolar-hyperplastic polyps, or atrophy of the surrounding mucosa based on the presence or absence of MWFL. Multivariate analyses showed that only oral PPI intake was a significant independent factor associated with MWFL after adjusting for covariates (p=0.001; OR, 5.78; 95% CI, 2.06ŌĆō16.2) (Table 2).

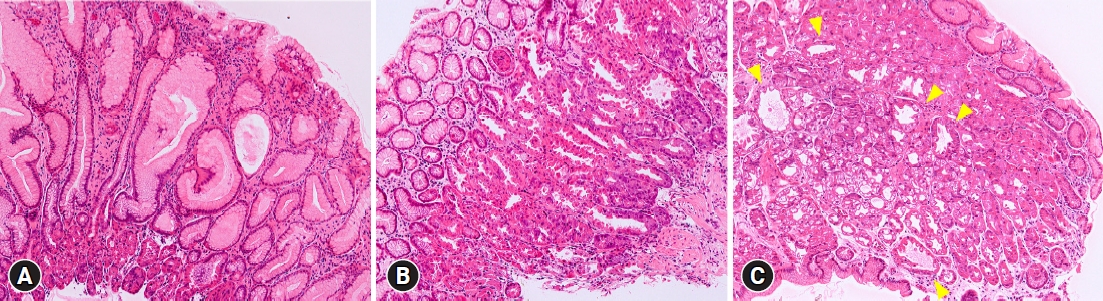

Targeted biopsies were obtained from the lesions of all patients with MWFL, and hyperplastic changes in the crypt epithelium were observed in 39 of 45 patients (86.7%) (Fig. 2A). Intestinal metaplasia was observed histopathologically in one (2.2%) of the 45 patients with MWFL. Moreover, 32 (71.1%) of the 45 patients with MWFL presented with parietal cell protrusion in the surrounding mucosa (Fig. 2B), while 16 (35.6%) exhibited oxyntic gland dilatation (Fig. 2C). The proportions of parietal cell protrusion and oxyntic gland dilatation in the surrounding mucosa were significantly higher in patients with MWFL than in those without MWFL (Table 3).

DISCUSSIONThe PPI use rate was 77.8% (35/45) in patients with MWFL and 30.5% (36/118) in those without MWFL. Multivariate analyses revealed that oral PPI intake was a significant independent factor associated with MWFL (p=0.001; OR, 5.78; 95% CI, 2.06ŌĆō16.2). Previous studies reported on PPI-associated polyps, including fundic gland polyps, hyperplastic polyps, and hemorrhagic polyps that form fundic gland polyps.1,11 We previously conducted a retrospective observational study and reported an association between MWFL occurrence and oral administration of antacids, endoscopic characteristics, and histopathological findings.4 However, no systematic and prospective studies are available on the association between MWFL occurrence and oral PPI intake, patient characteristics, and histopathological findings related to MWFL. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to show that oral PPI intake is a significant independent factor associated with MWFL occurrence.

This study investigated whether the presence or absence of MWFL caused by long-term oral PPI intake was associated with the presence or absence of fundic gland polyps and foveolar-hyperplastic polyps; however, the endoscopic findings associated with MWFL did not include cobblestone-like mucosa or black spots, which have been implicated in the long-term oral intake of PPIs, or the more recently reported gastric mucosal redness.15 We consider their association with these endoscopic findings an issue for future investigations.

The elevated portion of the MWFL was histologically characterized by hyperplastic changes in the crypt epithelium. Whether this histological change is due to hypergastrinemia or a direct effect of PPIs is unclear. Although this study showed that patients with MWFL presented a significantly higher incidence of hypergastrinemia, the direct effects of PPIs could not be ruled out, considering that oral PPI intake was a significant independent factor associated with MWFL after adjusting for covariates in the multivariate analyses. Further basic research, such as animal experimentation, is needed to clarify this point.

Reports of intestinal metaplasia as an endoscopic finding similar to MWFL in the gastric fundus are available.16-18 In this study, biopsies were performed of all patients with MWFL, and the histopathological findings revealed almost no intestinal metaplasia, indicating that MWFL are caused by foveolar hyperplasia and not intestinal metaplasia. In the mucosa surrounding the fundic glands, the incidence of parietal cell protrusion and oxyntic gland dilation was histologically higher in patients with versus without MWFL. Similar histological findings suggesting an association with PPI administration were previously reported.19,20 This might be reflected by the high number of patients with MWFL who received PPIs in this study.

The limitations of this study were that it was a single-center study conducted at a university hospital, and many patients presented with a history of early gastric cancer or high-risk gastric cancer with extensive atrophic gastritis or inflammatory bowel disease. Multicenter studies with various participants, including healthy volunteers, are required.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that oral PPI intake is an independent factor associated with the occurrence of MWFL.

NOTESAuthor Contributions

Conceptualization: RH, KY; Data curation: RH, KY; Formal Analysis: HA; Funding acquisition: KY; Investigation: RH, KY, TK, TH, YH, KT, KI, KO, YO, MM, TH, HT, AO; Project administration: RH, KY; Resources: SN; Supervision: KY, TU; WritingŌĆōoriginal draft: RH, KY; WritingŌĆōreview & editing: all authors.

Supplementary MaterialSupplementary Table 1. Details of PPI oral administration (types of PPI and duration of use). Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.257.

Fig.┬Ā1.Endoscopic features of multiple white and flat elevated lesions. (A) Standard observation using white light. The gastric fundus and corpus have numerous flat elevated lesions of various sizes and heights in white tones (arrowheads). (B) Observation following the indigo carmine dye application. Flat protrusions repelling the dye are observed on the surface. (C) Observation without magnification using NBI. The surrounding mucosa is brownish in color with increased contrast to the whitish flat elevated lesions, and the lesions are readily observed compared to the standard observation using white light. (D) Observation with magnification using narrow-band imaging. Demarcation lines are clearly observed at the base, and a microvascular pattern is absent. The microsurface pattern indicates a wider and oval-shaped marginal crypt epithelium, and the intervening parts between the crypts are wider with a brownish center compared to the surrounding mucosa.

Fig.┬Ā2.Histological characteristics of patients with multiple white and flat elevated lesions (MWFL). (A) Biopsy specimens from MWFL show foveolar hyperplasia. (B) Parietal cell protrusions are observed in the surrounding gastric mucosa in patients with MWFL. (C) Oxyntic gland dilatations (arrowheads) are observed in the surrounding gastric mucosa of patients with MWFL. (AŌĆōC) Hematoxylin and eosin staining, ├Ś20.

Table┬Ā1.Comparison of characteristics of patients with and without MWFL (univariate analysis) (n=163)

Table┬Ā2.Comparison of clinical background between patients with and without MWFL (multivariate analysis) (n=163) Table┬Ā3.Comparison of the histopathological findings of biopsy samples from the surrounding mucosa of patients with and without MWFL (n=163) REFERENCES1. Noffsinger A. Fenoglio-Preiser's gastrointestinal pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

2. Kawaguchi M, Arai E, Nozawa H. An investigation of white flat elevations in the gastric body. Gastroenterol Endosc 2007;49(Suppl 1):958.

3. Kamada T, Kawaguchi M, Maruyama Y, et al. New gastric lesion in the cardia induced by proton pump inhibitor treatment. Gastroenterology 2011;140(5 Suppl 1):SŌĆō719.

4. Hasegawa R, Yao K, Ihara S, et al. Magnified endoscopic findings of multiple white flat lesions: a new subtype of gastric hyperplastic polyps in the stomach. Clin Endosc 2018;51:558ŌĆō562.

5. Haruma K, Shiotani A, Kamada T, et al. Problems of prolonged administration of PPI-occurrence of gastric polyps. Shokakinaika 2013;56:190ŌĆō193.

6. Yamaoka R, Yao K, Chuman K, et al. Novel endoscopic findings of multiple white flat lesions: a new subtype of hyperplastic polyps in the stomach. United European Gastroenterol J 2016;3(Suppl 1):A386.

7. Ally MR, Veerappan GR, Maydonovitch CL, et al. Chronic proton pump inhibitor therapy associated with increased development of fundic gland polyps. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:2617ŌĆō2622.

9. Sugawara K, Imai Y, Saito E. Cases of gastric fundic gland polyps increasing in the size during the long-term therapy with proton pump inhibitor. Gastroenterol Endosc 2009;51:1686ŌĆō1691.

10. Hongo M, Fujimoto K; Gastric Polyps Study Group. Incidence and risk factor of fundic gland polyp and hyperplastic polyp in long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy: a prospective study in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2010;45:618ŌĆō624.

11. Takeda T, Asaoka D, Tajima Y, et al. Hemorrhagic polyps formed like fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor administration. Clin J Gastroenterol 2017;10:478ŌĆō484.

12. Aoi K, Yasunaga Y, Matsuura N, et al. Fundic gland polyp with dysplasia developed during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy, report of a case. Stomach Intest 2012;47:1270ŌĆō1274.

14. Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy 1969;3:87ŌĆō97.

15. Shinozaki S, Osawa H, Miura Y, et al. The effect of proton pump inhibitors and vonoprazan on the development of 'gastric mucosal redness'. Biomed Rep 2022;16:51.

16. Pimentel-Nunes P, Lib├ónio D, Lage J, et al. A multicenter prospective study of the real-time use of narrow-band imaging in the diagnosis of premalignant gastric conditions and lesions. Endoscopy 2016;48:723ŌĆō730.

17. Pimentel-Nunes P, Dobru D, Lib├ónio D, et al. White flat lesions in the gastric corpus may be intestinal metaplasia. Endoscopy 2017;49:617ŌĆō618.

18. Uedo N, Yamaoka R, Yao K. Multiple white flat lesions in the gastric corpus are not intestinal metaplasia. Endoscopy 2017;49:615ŌĆō616.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||