A Case of Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma of the Sigmoid Colon Presenting as a Semipedunculated Polyp

Article information

Abstract

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas are characterized by lymphoepithelial lesions pathologically. Colonic MALT lymphomas are relatively rarer than lymphomas of the stomach or small intestine. Endoscopically, colonic MALT lymphoma frequently appears as a nonpedunculated protruding polypoid mass and/or an ulceration in the cecum and/or rectum. We report a unique case of a colonic MALT lymphoma presenting as a semipedunculated polyp. A 54-year-old man was found to have a 2-cm semipedunculated polyp in the sigmoid colon during screening colonoscopy. The polyp was removed by endoscopic mucosal resection. Histologic examination of the resected polyp revealed diffuse epithelial infiltration by discrete aggregates of lymphoma cells. We diagnosed the tumor as low-grade B-cell MALT lymphoma by immunohistochemical staining.

INTRODUCTION

The term mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma was first coined by Isaacson and Wright1 in 1983. MALT lymphomas can occur in many locations, including the gastrointestinal tract, salivary glands, thyroid, lung, and breast. It is histologically characterized by lymphoepithelial lesions and lymphoplasmic epithelial invasion.1,2 Lymphomas that occur in the colon account for 10% to 20% of lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract, 2.5% of all lymphomas, and 0.2% to 0.6% of colorectal malignant tumors, and thus, are rare.2,3 Most of the colonic MALT lymphomas present as a nonpedunculated protruding polypoid mass and/or ulceration. Cases of primary colonic MALT lymphoma reported in Korea have presented as multiple submucosal tumors (one case),4 a nonpedunculated protruding polypoid mass (four cases),5,6,7,8 obstructive lesions of the colon caused by mucosal edema or a tumor (two cases),9,10 or mucosal discoloration (one case).11 Here, we report the case of a colonic MALT lymphoma presenting as a semipedunculated polyp that was removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old man visited Daegu Catholic University Hospital after a screening colonoscopy that revealed a sigmoid colon polyp that was diagnosed pathologically as a tubular adenoma. He denied other symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, general weakness, loss of appetite, or hematochezia. His blood pressure was 106/64 mm Hg, pulse rate 73 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, and body temperature 36.7℃. His consciousness was clear, and no lymphadenopathy was evident in the head and neck, axillary, or inguinal region. Abdominal examination revealed no tenderness or rebound tenderness. Bowel sounds were normal, and the liver and spleen were not palpable. The laboratory findings were as follows: white blood cells, 11,400/mm3 (neutrophils 81.8%, eosinophils 0.4%, lymphocytes 12.4%); hemoglobin, 13.4 g/dL; and platelet count, 202,000/mm3. The blood chemistry test showed the following results: aspartate aminotransferase, 16 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 21 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dL; alkaline phosphatase, 129 IU/L; total protein, 6.5 g/dL; albumin, 4.4 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 12.2 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.9, mg/dL; Na, 139 mEq/L; K, 3.4 mEq/L; and Cl, 98 mEq/L. The serum carcinoembryonic antigen level was 2.69 ng/mL, which was within the reference range.

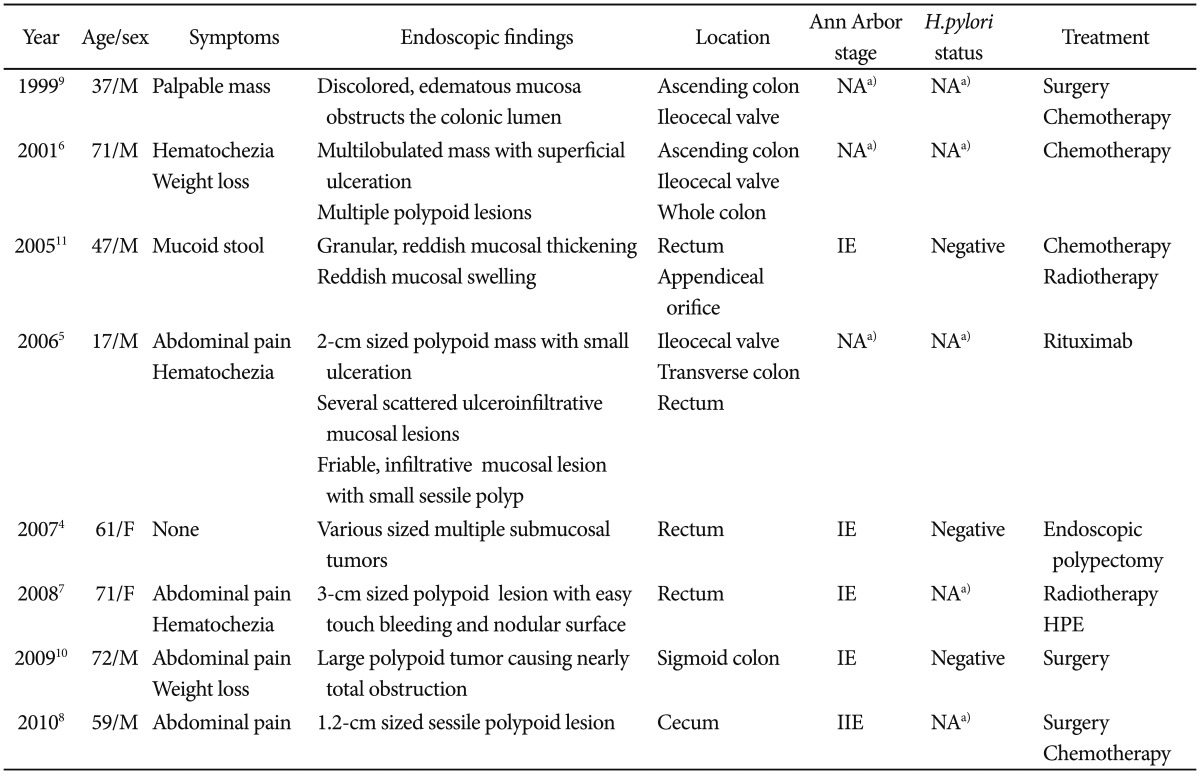

Colonoscopy revealed a semipedunculated polyp, approximately 2 cm in size, in the sigmoid colon. The surface of the polyp showed redness and nodularity (Fig. 1A). In private clinics, the tumor was diagnosed as a tubular adenoma; however, a diagnosis of submucosal tumor was not completely ruled out. We performed EMR by en bloc resection of the polyp with a flex knife and a snare after injecting a glycerin solution into the submucosa (Fig. 1B, C).

Colonoscopic findings. (A) Colonoscopy image showing a solitary semipedunculated polyp with nodular and erythematous mucosa originating from the sigmoid colon. (B) The polyp was resected with a snare after mucosal incision with a flex knife. (C) The resected polyp was 2 cm in size. (D) Follow-up sigmoidoscopy (2 months after resection) showed a postendoscopic mucosal resection scar.

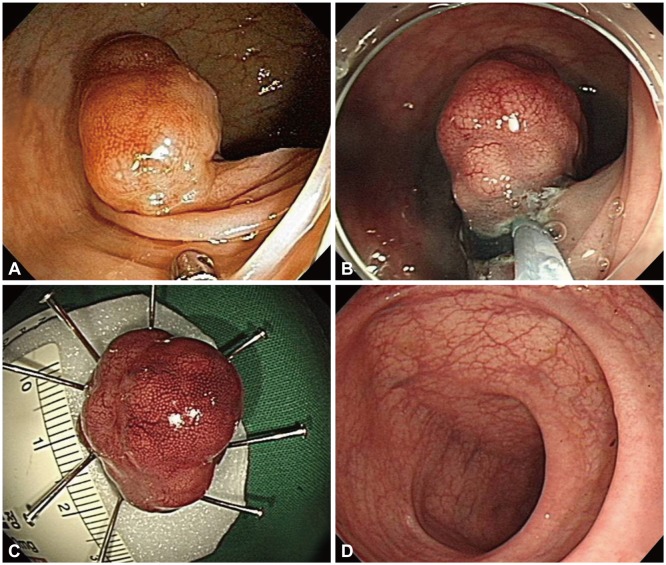

Resected specimens histologically showed lymphoepithelial lesions with diffuse proliferation of atypical lymphocytes, which immunohistochemically stained positively for CD20, CD5, and Bcl-6, but negatively for CD3, Bcl-2, and cyclin D1. In addition, the Ki-67 labeling index was 10% to 20%. These findings were compatible with low-grade B-cell MALT lymphoma (Fig. 2).

Histologic findings. (A) Lymphoma cells, with small to medium-sized nucleoli with pale cytoplasm, infiltrated the reactive follicles. The epithelium was invaded and destroyed by discrete aggregates of lymphoma cells (arrows) (H&E stain, ×200). (B) Immunohistochemical staining revealed lymphoma cells with a diffuse immunoreaction for CD20 (Immunostain for CD20, ×200). (C) Immunohistochemical staining revealed that lymphoma cells were not immunoreactive for cyclin D1 (Immunostain for cyclin D1, ×200).

There was no evidence of lymph node metastasis or involvement of any other organ, except for a gallstone, in the thoracic and abdominal computed tomography performed for staging. According to the Ann Arbor staging system, the tumor was stage IE.

The resected lesion was replaced with normal mucosa on sigmoidoscopy 2 months after the EMR (Fig. 1D). He has been free of disease during 10 months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

MALT lymphoma, a subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, is classified as an extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and is a lymphoepithelial lesion characterized by epithelial infiltration by lymphoplasma cells.1,2 MALT lymphoma of the stomach is known to be associated with Helicobacter pylori infection,11 whereas nongastric MALT lymphomas have been associated with Borrelia burgdorferi, Chlamydia psittaci, hepatitis C virus, Campylobacter jejuni, and autoimmune disease.12

Colonic MALT lymphoma occurs at an average age of 59.8 years and shows no sex preference. Clinically, it is usually asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms such as bloody diarrhea and/or abdominal pain. However, in some rare cases, intestinal obstruction or intussusception can appear.9,10,13,14 Systemic symptoms such as fever and weight loss are rare because most MALT lymphomas are well localized and slow growing.12

According to endoscopic findings, a MALT lymphoma of the colon usually appears as a sessile protruding lesion or ulcerative lesion, and the former is approximately 10 times more common than the latter.14,15 Sites of tumor growth have been reported to be the cecum (71.5%), rectum (16.9%), and ascending colon (6.2%); however, the sigmoid colon is only rarely affected.16

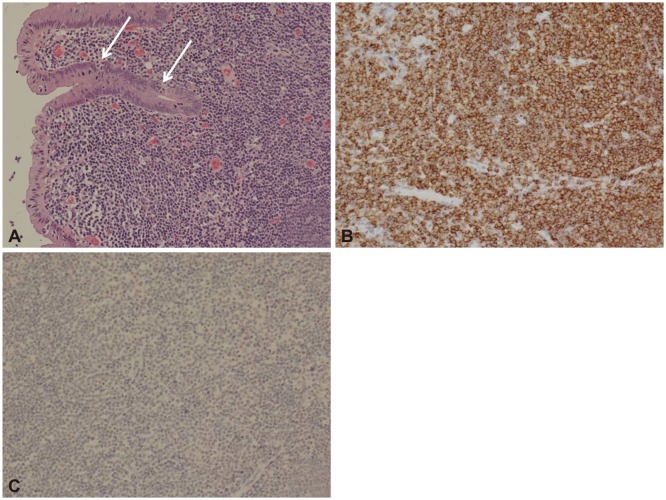

Eight cases have been reported in Korea, and these are summarized in Table 1. These cases manifested as polypoid lesions, neoplastic lesions, and protruding lesions in the form of submucosal tumors,4,5,6,7,8,10 but only rarely in the form of luminal stenosis caused by thickening of the large intestine wall or a color change of the mucosa.9,11 Both neoplastic and polypoid lesions are sessile and accompanied by ulcers or nodularities in the mucosal lesion.5,6,7,8,10 In terms of regions of occurrence, five cases have been reported in the rectum,4,5,6,7,11 five cases in the appendix or ileocecal valve,5,6,8,9,11 and two cases in the ascending colon.6,9 Accordingly, a MALT lymphoma presenting as a semipedunculated polyp in the sigmoid colon is extremely rare.

A MALT lymphoma can be diagnosed during surgery or endoscopic biopsy. In the case of endoscopic biopsy, the submucosa must be collected because lymphomas can be limited to this region.4 In the present case, the tumor was diagnosed as a MALT lymphoma by EMR, which included the submucosal tissue, whereas it had been diagnosed as a tubular adenoma at private clinics.

The specific histological findings of MALT lymphoma include lymphoepithelial lesions by lymphoplasmic epithelial invasion, centrocyte-like cells, and reactive lymphoid follicles. Plasma cell differentiation is observed in one-third of all MALT lymphomas.17 However, it is difficult to differentiate MALT lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the presence of multiple lymphoid follicles.14 Moreover, MALT lymphoma is often confused with mantle cell lymphoma because of their histologic similarities. However, MALT lymphoma usually presents as a single lesion, whereas mantle cell lymphoma presents as multiple lymphomatous polyposis in the gastrointestinal tract and without lymphoepithelial lesions.18

Immunohistochemically, these two types can be differentiated by the cyclin D1 status because MALT lymphomas and mantle cell lymphomas are immunonegative and immunopositive for cyclin D1, respectively.14 In our case, histological findings showed that lymphoepithelial lesions were caused by the invasion of the mucosa by atypical lymphocytes, and that they were cyclin D1 negative with a Ki-67 labeling index of 10% to 20%, which indicated a diagnosis of low-grade MALT lymphoma.

Because of the lack of an accepted etiology and the limited number of cases, no guideline has been issued for the treatment of colonic MALT lymphomas. Locally extended low-grade MALT lymphomas are currently treated by endoscopic or surgical excision, whereas high-grade MALT lymphomas and MALT lymphomas with multiple organ involvement may be treated using different modalities such as surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and, more recently, rituximab therapy.5 However, there is no standard treatment. Some have reported that antibiotic treatment against H. pylori is effective for colonic MALT lymphoma, and that this treatment influences even H. pylori-negative patients,19 which suggests that some strains sensitive to antibiotics for H. pylori eradication contribute to MALT lymphoma development in these patients. Grunberger et al.20 reported that the administration of antibiotics against H. pylori was ineffective in H. pylori-positive MALT lymphoma patients with extragastric involvement. Some case reports published in Korea have addressed the efficacy of H. pylori treatment in MALT lymphoma. However, the results in these cases were inconclusive as the presence of H. pylori infection was uncertain and the patients had undergone radiotherapy.7 Therefore, the efficacy of H. pylori treatment in MALT lymphoma requires further study. Our patient was not tested for H. pylori, and because MALT lymphoma was localized to the sigmoid colon, no measures other than endoscopic mucosal excision were performed.

In the described case, MALT lymphoma presented as a semipedunculated polyp during colonoscopy, and diagnosis and treatment planning were performed on the basis of the results of EMR. The lesion did not recur for 10 months after the EMR. More case reports and studies about colonic MALT lymphoma presenting with variable morphology are needed to establish guidelines for the treatment of colonic MALT lymphomas in the near future.

Notes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.