Improving the Endoscopic Detection Rate in Patients with Early Gastric Cancer

Article information

Abstract

Endoscopists should ideally possess both sufficient knowledge of the endoscopic gastrointestinal disease findings and an appropriate attitude. Before performing endoscopy, the endoscopist must identify several risk factors of gastric cancer, including the patient's age, comorbidities, and drug history, a family history of gastric cancer, previous endoscopic findings of atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia, and a history of previous endoscopic treatments. During endoscopic examination, the macroscopic appearance is very important for the diagnosis of early gastric cancer; therefore, the endoscopist should have a consistent and organized endoscope processing technique and the ability to comprehensively investigate the entire stomach, even blind spots.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the second most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in Korea.1 Recent advances in endoscopic technology and heightened interest in public health have led to rapid developments in endoscopic screening tests. Patients with early gastric cancer (EGC) have excellent prognoses and 5-year survival rates exceeding 90%. Furthermore, endoscopic submucosal dissection has become a common treatment modality for EGC without lymph node metastasis. Gastrointestinal endoscopy is a very good medical technique for screening and treatment. The endoscopy-related diagnostic rate of EGC recently reached 80%, and the mortality rate of gastric cancer is gradually decreasing.23 Thus, endoscopy and biopsy are primarily recommended as tests for the diagnosis of gastric cancer.

However, since some EGCs are only diagnosed on the basis of very delicate changes in the mucosa, extremely careful observation and close biopsy examination are required. In a recent cohort study in England, 2,727 retrospectively tested patients with gastric cancer had an endoscopy miss rate of approximately 8.3%. This miss rate was especially high in patients <55 years (p=0.03) and in female patients (p=0.01).4 In a study by Lee et al.,5 of the 109 lesions in 51 patients with gastric cancer who had undergone gastrectomy and were diagnosed with synchronous multifocal gastric carcinoma, 16 lesions (14.6%) were missed on presurgical endoscopy.

Interval gastric cancer is defined as gastric cancer diagnosed within 2 years after negative endoscopy findings. Cho et al.6 recently analyzed 284 patients with gastric cancer and found that 52 (18.2%) had interval gastric cancer. In this study, the average interval between endoscopy and a cancer diagnosis was 12.6 months, while the average EGC lesion size was 1.3 cm. In addition, many cases were accompanied by intestinal metaplasia. Therefore, it should be considered that many EGC lesions can be missed on endoscopy. This study aimed to improve the early detection of gastric cancer by reviewing previous research. To this end, we investigated some of the principles of preparation for endoscopy and attitudes about the procedure, and discussed the endoscopic findings of EGC.

HIGH-RISK GASTRIC CANCER GROUPS

Gastric cancers are caused by a combination of various factors, including genetic traits, environmental factors, and Helicobacter pylori infection. More specifically, the incidence of gastric cancer increases two to three times in people with a family history of the disease.7 In addition, many studies have reported H. pylori as an important factor causing gastric adenocarcinoma. H. pylori causes chronic gastritis of the gastric mucosa and subsequent atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia, which finally leads to adenocarcinoma. According to Vannella et al.,8 atrophic gastritis associated with H. pylori causes gastric cancer in 0.6% to 1.1% of cases. Furthermore, the degree of atrophic gastritis, the existence of intestinal metaplasia, and age are the risk factors of the transformation of atrophic gastritis into gastric cancer. One cohort study presented in the Netherlands reported annual incidence rates of gastric cancer of 0.1% from atrophic gastritis, 0.25% from intestinal metaplasia, 0.6% from low-grade dysplasia, and 6% from high-grade dysplasia.9

According to a study by Bang and Kim10 people are at a particularly high risk of gastric cancer if intestinal metaplasia invades 20% or more of the gastric mucosa, histologically incomplete intestinal metaplasia is present, or they smoke or have a family history of gastric cancer. Therefore, people who have atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia should undergo periodic check-ups and should be followed closely. In particular, it is very difficult to make a diagnosis of EGC if a patient has severe intestinal metaplasia; therefore, close observation is also required in such cases.

Gastric adenoma is unquestionably a precancerous lesion that accounts for 5% to 10% of gastric polyps, and the cancer potential increases with the degree of histological dysplasia. A reported 11% of gastric adenomas progress to gastric cancer within 4 years of follow-up. Therefore, even in adenoma, thorough endoscopic checks and histological examinations in the presence or absence of a cancerous lesion.

ENDOSCOPIC EXAMINATION WITHOUT BLIND SPOTS

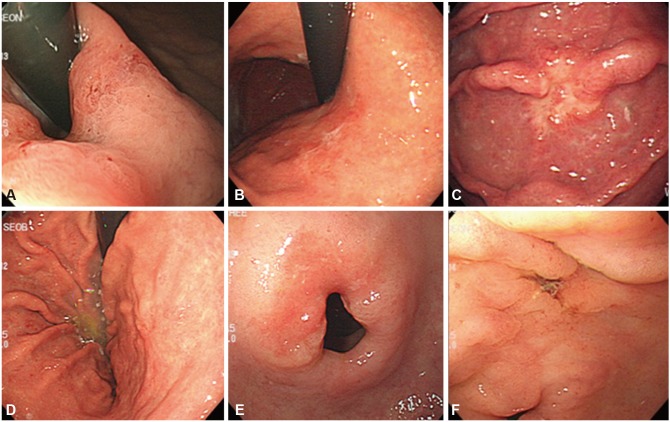

A recent analysis of the endoscopic miss rate of 103 patients with EGC and high-grade dysplasia revealed that the miss rate of lesions in the esophagogastric junction area was statistically high (p=0.022), while lesions in the upper gastric area were relatively more frequently missed than those in the lower gastric and antral areas.11 It is well known that the blind spots of upper gastric endoscopy are the cardia, greater curvature of the upper part, posterior area of the body, pyloric area, and lesser curvature of the antrum (Fig. 1).

Endoscopic findings of various early gastric cancer (EGC) lesions in the blind spot areas. (A) A flat erythematous lesion (EGC 0-IIb) at the cardia. (B) An irregular flat lesion (EGC 0-IIb) in the posterior wall of the upper body. (C) A disrupted mucosal fold (EGC 0-IIc) in the greater curvature of the upper body. (D) A discolored flat lesion (EGC 0-IIb) in the posterior wall of the lower body. (E) A reddish flat lesion (EGC 0-IIb) in the P-ring. (F) A well-demarcated depressed lesion (EGC 0-IIc) in the lesser curvature of the antrum.

Since a specific area of the cardia is covered by the scope itself during endoscopy, it should be inspected from different angles by rotation of the scope and the use of U-turns and J-turns. Additionally, the fundus can be checked using retroversion of the scope on the cardia as well as by inferior migration and careful observation of the lesser curvature and posterior wall. In particular, since the posterior wall of the great curvature is usually not fully exposed, concomitant aeration and suction should be performed to ensure clear visibility. During scope removal, the body and posterior wall of the cardia should be checked again along with the anterior wall of the greater curvature and the fundus.

The great curvature of the body is clearly observable after the removal of retained gastric fluid and aeration. When observing this area, one should pay attention to whether the fold and thickness of the great curvature are well expanded after aeration and whether there are any changes in color or differences in fold shape or thickness. Any gastric fold running differently to the adjacent folds indicates an ulcerative lesion at the end of the fold that should be carefully inspected.

The lesser curvature of the antrum, a well-known blind spot, can be seen by scope retraction with the tip directed upward and observation in near and far views by repeating the same procedure of moving upward and downward and changing the perspective.

The posterior part of the proximal antrum is another area that can be missed. During the observation of this area from one angle, the tip of the scope should be twisted to the right to reveal the mucosal layer shape. The area can again be seen during scope removal after straightening. An endoscopist should always try to remove all mucus attached to the mucosa by using adequate aeration and suction and should observe the lesion closely.

Serial steps of examination and filming are also recommended to ensure that blind spots are not missed during endoscopic examination. Indeed, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy announced a standardized filming recommendation to enhance endoscopy quality.12 Furthermore, Yao13 recently reported the use of 22 basic endoscopic films of each area to ensure an endoscopy that is free of blind spots.

ENDOSCOPIC FINDINGS OF EGC

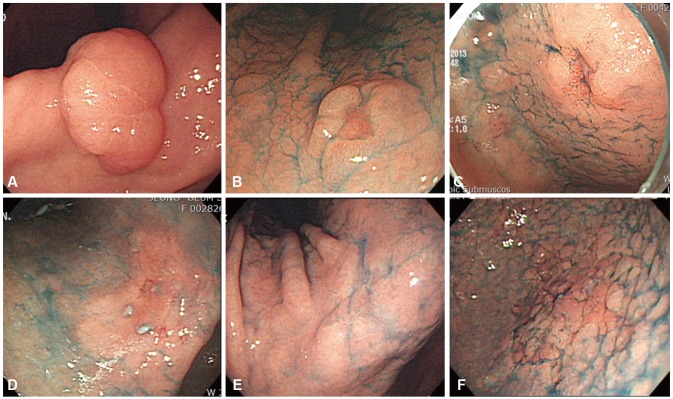

The newest endoscopic technologies of magnification endoscopy and narrow band imaging (NBI) endoscopy, which comprise image-enhanced endoscopy, are very helpful for characterizing gastrointestinal lesions; however, white light endoscopy remains the core endoscopic technology for detecting EGC.14 EGC has various morphologies, from subtle mucosal surface changes to color changes (Fig. 2). According to recently reported endoscopic findings in Korea, of 1,942 patients, 306 (16.6%) were diagnosed with elevated-type EGC, 528 (28.6%) with flat-type EGC, and 1,011 (54.8%) with depressed-type EGC. Intestinal-type EGC and well/moderately differentiated lesions were macroscopically observed as elevated-type EGC, while signet ring cells and poorly differentiated lesions were observed as relatively flat and depressed types (p<0.001).15 Protruded (0-I) and excavated (0-III) types are fairly easily diagnosed by endoscopic examination, whereas superficial (0-II) types are not since some superficial types of cancer resemble gastritis.16

Endoscopic findings of early gastric cancer (EGC) lesions. (A) A whitish, elevated flat lesion (EGC 0-IIa) shown at an angle. (B) A doughnut-like elevated lesion (EGC 0-IIc) in the lesser curvature of the lower body. (C) A reddish depression (EGC 0-IIc) in the lesser curvature of the antrum. (D) Reddish mucosal changes (EGC 0-IIb) in the angle. (E) Whitish mucosa changes (EGC 0-IIb) in the angle. (F) Granular mucosal changes (EGC 0-IIb) in the greater curvature of the lower body.

Superficial depressed lesions (0-IIc)

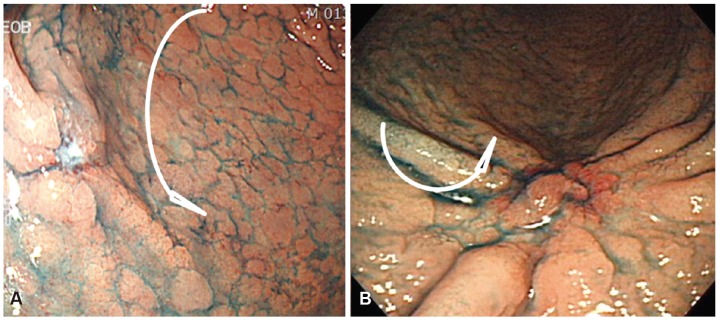

Depressed lesions, such as erosions and ulcers, show a variety of types ranging from those that are definite to those that are not. Deep depressions, those accompanied by definite elevations, and clear-colored lesions are easily observed. A characteristically depressed lesion can be accompanied by converging folds, which can show abrupt cutting, clubbing, fusion, or a rat-tail appearance (Figs. 3, 4).

Endoscopic findings. (A) A mucosal convergence is noted, but no elevation at the tip of the converging folds is seen, and the depth of invasion is thus diagnosed as limited to the mucosa. (B) Remarkable elevation of the tumor is seen with a converging fold. These findings fulfill the criteria for massive submucosal invasion by cancer.

However, shallow depressions can easily be overlooked. Therefore, the need arises to adjust the endoscope angle and direction as well as the distance, air supply, and air intake. If concave/convex changes or color differences, blood vessel projections, or gloss differences in the surface and mucosa are observed on endoscopy, a closer observation should be performed using chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine spray or endoscopy for image enhancement. When a shallow or local depression that differs from the surrounding normal mucosa is seen, it is important to determine whether the lesion is normal or malignant. Accordingly, a biopsy should be conducted to evaluate the color differences compared to the surrounding normal mucosa and observe whether the boundary, shape, and color of the depressed surface is worm-eaten or has been encroached upon.

Superficial flat lesions (0-IIb)

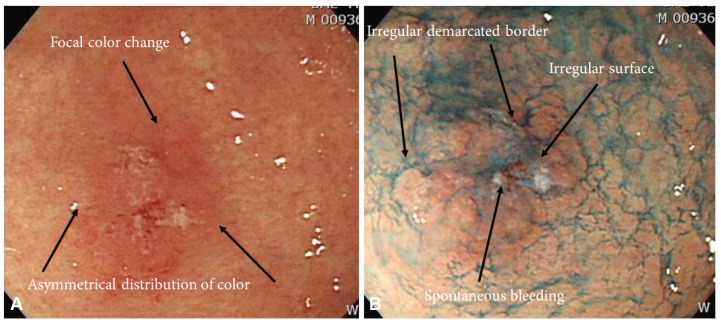

Type IIb lesions are nearly flat and have redness and sometimes, a whitish discoloration (Fig. 5). Compared with the surrounding normal mucosa, an irregular vascular bed or disappearance without a color change is observed. The permeable vascular bed can be irregularly discolored in places. Excessive aeration could make it difficult to recognize pathological lesions; therefore, if an endoscopist finds an abnormal site, he or she should repeatedly use aeration and suction in an effort not to miss the pathological lesions. Differentiated type IIb lesions generally look red because a tumor can have proliferated capillaries in the submucosal layer and a continuously clear boundary. In contrast, undifferentiated type tumors intermittently infiltrate the normal gastric glands through the mucosa's middle to deep layers. Therefore, because these tumors retain a normal, noncancerous epithelium, a whitish discoloration on the surface is frequently observed. There are many cases of uncertain boundaries and no capillary proliferation in the lamina propria mucosae.17

Superficial elevated lesions (0-IIa)

Type I EGC is relatively easy to find during endoscopic examinations. This type appears as a sessile or semi-pedunculated mucosal mass that is bigger than a benign polyp. This is occasionally accompanied by bleeding and shows a granular or lobular appearance with mucosal changes, erosion, or depressions. Compared to type I, type IIa is slightly more elevated than the adjacent mucosa. This type shows an irregular surface as well as redness or paleness. These lesions can be limited to the mucosa without significant mucosal fold changes. If there are significant mucosal fold changes or central dimpling, submucosal infiltration is highly probable.

CHROMOENDOSCOPIC EXAMINATION

Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine, the most commonly used staining agent, is helpful for clarifying endoscopic findings that are ambiguous on conventional endoscopy. Its use also helps discern small erosive lesions that are only depressed in the center but have no surrounding mucosal elevation. However, issues arise with chromoendoscopy when staining dyes are used and subsequently unclear endoscopic findings are noted. These issues include the inconveniences of applying staining agents, uneven spreading, and lesion stagnation. Chemical staining methods using methylene blue and acetic acid have reportedly helped with the diagnosis of some cases of EGC. Lee et al.18 recently reported that serial application of acetic acid and indigo carmine is helpful for diagnosing EGC and clarifying marginal locations. Nevertheless, the chemical staining method is not universally used in actual clinical practice compared to the indigo carmine method.

The introduction of various advanced image-enhanced endoscopic technologies such as magnifying endoscopy and NBI in recent years compensates for the aforementioned weaknesses of the indigo carmine and chemical staining methods. However, the stomach cavity is wide, and its subepithelial capillary network is well developed compared to that of the esophagus. Therefore, it is difficult to observe lesions using NBI since they appear to dark and grainy on the subsequent images. To observe the overall gastric area and diagnose any lesions, experts recommend first using white light endoscopy to locate any suspected lesions and then use NBI for further evaluation. This enables the observation of the microvascular (MV) patterns and microsurface (MS) structures of suspected lesions during the diagnostic process.19 Experienced endoscopists in the Asia-Pacific region generally feel that NBI is not useful for detecting EGC and recommend that endoscopists be trained in conventional endoscopy or chromoendoscopy to detect EGC.20 In real clinical practice, advanced magnifying and image-enhanced endoscopes are much more helpful in the analysis of lesions, targeting of biopsies, and determination of marginal locations for endoscopic resection since they enable visualizing of the unevenness and existence of MV patterns and MS structures.21

CONCLUSIONS

Although endoscopy is a well-developed and advanced technique, the responsibility of performing endoscopy well and making an accurate diagnosis remains with the endoscopist. For these reasons, endoscopists should take a patient's past history before the procedure to predict their risk of gastric cancer and examine the patient conscientiously with a modest attitude. Furthermore, when an operator encounters a lesion that has some features of malignancy, he or she should record this in detail and perform an endoscopic biopsy. Finally, the endoscopist must provide the patient with a comprehensive consultation after the procedure as well as follow-up whenever indicated.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no financial conflicts of interest.