Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Liver Biopsy Using a Core Needle for Hepatic Solid Mass

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) using a core needle for hepatic solid masses (HSMs). Additionally, the study aimed to assess factors that influence the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNB for HSMs.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of patients who underwent EUS-FNB for the pathological diagnosis of HSMs was conducted between January 2013 and July 2017. The procedure had been performed using core needles of different calibers. The assessed variables were mass size, puncture route, needle type, and the number of needle passes.

Results

Fifty-eight patients underwent EUS-FNB for the pathologic evaluation of HSMs with a mean mass size of 21.4±9.2 mm. EUS-FNB was performed with either a 20-G (n=14), 22-G (n=29) or a 25-G core needle (n=15). The diagnostic accuracy for this procedure was 89.7%, but both specimen adequacy for histology and available immunohistochemistry stain were 91.4%. The sensitivity and specificity of EUS-FNB were 89.7% and 100%, respectively. There was one case involving bleeding as a complication, which was controlled with endoscopic hemostasis. According to the multivariate analysis, no variable was independently associated with a correct final diagnosis.

Conclusions

EUS-FNB with core biopsy needle is a safe and highly accurate diagnostic option for assessing HSMs. There were no variable factors associated with diagnostic accuracy.

INTRODUCTION

Liver biopsy (LB) is a useful method for the evaluation and management of hepatic lesions. The biopsy result impacts the diagnosis and prognosis, as well as management decisions. Although the use of LB has reduced with the development of cross-sectional imaging, a histologic evaluation might still be necessary for indeterminate hepatic solid masses (HSMs) or to confirm metastasis [1]. Ultrasonography (US) or computed tomography (CT)-guided LB is typically used for the diagnosis of HSMs. There are however several procedure-related complications, most commonly pain at the biopsy site or hemorrhage. Bile peritonitis, hypotension, pneumothorax, tumor seeding, or death have also been reported [2,3]. In the past few years, significant progress was made in assessing the usefulness of alternative technologies and approaches to evaluate HSMs.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has been a well-established method for the management of various pathological conditions such as gallbladder, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and intra-abdominal lymph node [4-7]. The usefulness of EUS-FNA for liver disorders has also been investigated [8-10]. Furthermore, this procedure has been shown to yield similar results as those obtained by percutaneous or trans-jugular LB [11]. However, it might remain below due to the inadequate the specimen for pathologic evaluation, or sampling errors related to the lesions in the absence of rapid on-site pathologic evaluation (ROSE). Various needle designs have been developed to improve the diagnostic yield. A core needle, flexible with reverse bevel design, is thought to obtain good quality histology samples of the core tissues and is easily accessible. The specimens obtained using EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) with a core needle are believed to provide preserved tissue architecture, as well as an opportunity to evaluate the immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of the tissue, thus improving the diagnostic accuracy, especially in situations without ROSE. Until now, there have been few studies about EUS-FNB using a core needle for HSMs. In this retrospective analysis, we aimed to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of EUS-FNB using core needle for HSMs. In addition, we also aimed to assess the factors that influence the diagnostic accuracy of the procedure for HSMs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient characteristics

Consecutive patients who underwent EUS-FNB for HSMs between January 2013 and July 2017 at a single tertiary referral center were included in this analysis. We excluded patients who had incomplete information about the procedure, cases with insufficient information to enable a final diagnosis and those that were lost to follow-up. We conducted a retrospective analysis of a prospectively-maintained database about EUS in our center. All patients underwent imaging studies (abdominal ultrasound, CT scan, or magnetic resonance imaging) before EUS. This study received approval from the ethics committee of our institution (WKUH 2017-08-013-002).

EUS-FNB procedure

After informed consent was obtained from all patients or their relatives, EUS-FNB was performed using an oblique viewing linear scanning echoendoscope (GF-UCT260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), with the patient in the left lateral decubitus or prone position, under moderate sedation using intravenous midazolam and pethidine. All the procedures were performed by a well-experienced endoscopist (THK and HKC). Hepatic masses were visible under EUS and a contrast agent such as Sonazoid® (Daiichi-Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) was used to obtain more details of the lesion. After evaluation, the mass was punctured using a 20-G, 22-G or 25-G core needle (Echotip ProCore® HD Ultrasound biopsy needle; Wilson-Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA) at the discretion of the endosonologist, avoiding regional vasculature under color Doppler via the trans-gastric or trans-duodenal route. Once the needle was advanced into the mass, the stylet was removed. A 10 mL negative suction or slow pull technique was applied, and the needle was moved to-and fro within the mass, more than 10 times in a single puncture session using a fanning method. The samples obtained were placed on glass slides by reinserting the stylet into the core needle. The puncture procedure was repeated up to 5 times until a whitish material, which was macroscopically visible, was obtained [12]. All procedures were conducted without an on-site pathologist. Each specimen was divided between a formalin bottle, smear, and a cellblock for histopathology. The assessment of pain was recorded after the procedure using a visual analogue scale ([VAS]; 0: no pain to 10: the worst pain). All adverse events were documented.

Pathologic assessment

The pathological diagnosis was made using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining with IHC staining, if available. The pathologist evaluated the adequacy of the specimen obtained with EUS-FNB, based on the number of all cell-types including tumor cells or normal hepatocytes, and the quality of each specimen, including the amount of blood, degree of tissue crushing, and contamination.

Study definition

In this study, sample adequacy was defined as a good-quality specimen obtained by EUS-FNB, sufficient to establish a pathological diagnosis. Non-diagnostic specimens were defined as either those with inadequate cellularity to characterize lesions or those unrepresentative of the target lesion. The final diagnosis was based on the surgical pathology or the EUS-FNB result considering compatible radiology with clinical characteristics on a follow-up at more than 6 months.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables pertaining to the baseline characteristics were analyzed as mean±standard deviation and range. Categorical parameters were described as frequency and proportion. The number of needle passes is presented as the median (range). A multivariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to identify the variables (mass size, needle type, route of puncture, and number of needle passes). The diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were calculated. Accuracy was defined as the ratio of the sum of true positive and true negative values divided by the number of the lesions. A p-value of <0.05 was set to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

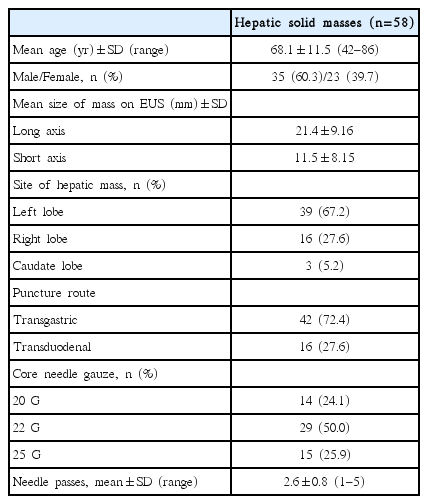

In total, 1,934 EUS examinations were performed during this study, and 325 patients underwent EUS-FNB for various indications. Of these, 58 patients (35 males and 23 females; mean age: 68.0±10.6 years) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Baseline characteristics of the patients and their lesions are indicated in Table 1. The mean size of the mass was 21.4±9.16 mm × 11.5±8.15 mm. The biopsy target site was the left lobe in 39 patients, the right lobe in 16 patients, and the caudate lobe in 3 patients. The number of procedures through the trans-gastric route and trans-duodenal route were 39 (67.2%) and 19 (32.8%), respectively. The needles used were 20-G (n=14), 22-G (n=29), or 25-G core needle (n=15). In total, 149 needle passes were performed, with a mean number of 2.6±0.8 (range of 1–5) per lesion.

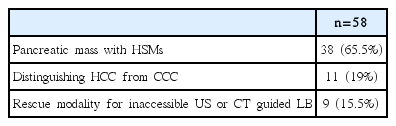

The indications for EUS-FNB for HSMs are presented in Table 2. The indications were: pancreatic mass with HSMs on cross-sectional imaging (Fig. 1); distinguishing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from cholangiocarcinoma (CCC) in cases that were difficult to differentiate on cross-sectional imaging (Fig. 2); difficulty in obtaining a tissue sample through US-or CT guided LB owing to poor accessibility or invisible target lesions (Fig. 3).

Indication of Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Tissue Acquisition Using Core Needle Biopsy for Hepatic Solid Masses

(A) Endoscopic ultrasonography imaging showing a 1.1 cm sized, encapsulated, homogenous isoechoic mass in the left lobe of the liver (white arrow). (B) The core needle is visible in the center of the mass (open arrow). (C) The endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy specimen shows tumor nests (arrows) and adjacent normal hepatocytes (arrowhead) (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], ×100). (D) The small-cell carcinoma shows nuclear molding (arrow) and crushing artifact (arrowhead) (H&E, ×400), these tumor cells are immunoreactive for neuroendocrine markers, likely CD56 (E) (CD56, ×200) and synaptophysin (F) (Synaptophysin, ×200).

(A) Magnetic resonance imaging showing a large heterogeneously increasing mass on the right lobe of the liver, which was difficult to differentiate between hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma (white arrow). (B) A hypoechoic mass with core needle on endoscopic ultrasound. (C) Polygonal hepatocytes with a higher than normal N/C ratio show a trabecular growth pattern with intervening sinusoids (hematoxylin and eosin, ×200). (D) These cells were immunoreactive for hepatocyte specific antigen (Hepatocyte specific antigen, ×200).

(A) An abdominal computed tomography scan showing an ill-defined hypoechoic mass (black arrow), on the caudate lobe of liver, which was difficult to access through percutaneous liver biopsy. (B) Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy with 22 G needle was performed and the mass was diagnosed as metastatic adenocarcinoma.

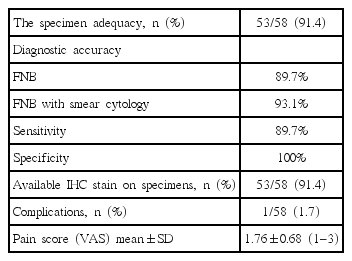

The rate of sample adequate for histology and diagnostic accuracy by EUS-FNB was 91.4% (53/58) and 89.7% (52/58), respectively. Their sensitivity and specificity were 89.7% and 100%, respectively. The diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity with addition of smear cytology increased to 93.1%. IHC staining was conducted on 91.4% (53/58) of specimens, and 3 patients were subsequently diagnosed with a neuroendocrine tumor. Procedure-related complications occurred in only one case of hemorrhaging (1.7%), which was successfully managed by endoscopic hemostasis. The mean VAS score was 1.76±0.68 and 50 patients (86.2%) had a pain score below 2 (Table 3).

The EUS-FNB diagnoses and final diagnoses are shown in Table 4. Six cases were non-diagnostic on EUS-FNB. Among them, 4 cases (6.9%) were subsequently confirmed as CCC after surgical resection and 2 cases (3.4%) were diagnosed as metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma by smear cytology. No other patients who underwent EUS-FNB exhibited any clinical or radiological evidence that was incompatible with their original pathologic diagnosis.

Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Diagnosis and Final Diagnosis in 58 Cases with Hepatic Solid Masses

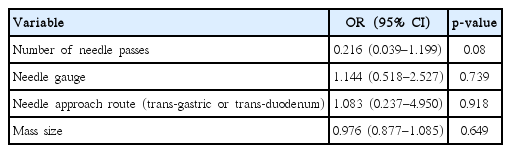

The analysis of factors that might influence the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNB for HSMs revealed no significant associations. The presence of a larger mass was not associated with better diagnostic accuracy. There was no correlation between the needle type and diagnostic accuracy. There was also no significant association between the route of puncture or the number of needle passes with diagnostic accuracy (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We performed a single-center retrospective study of patients with HSMs, to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of EUS-FNB using core needle, specifically-designed to obtain tissue samples for histologic diagnosis. We found that EUS-FNB using a core needle for HSMs had a high diagnostic accuracy (89.7%), sensitivity (89.7%), specificity (100%), and sample adequacy (91.4%) for histology, with an acceptable safety profile. This result is consistent with the 90.5% diagnostic accuracy shown by the core biopsy in a preliminary single-center study limited to 21 patients [13].

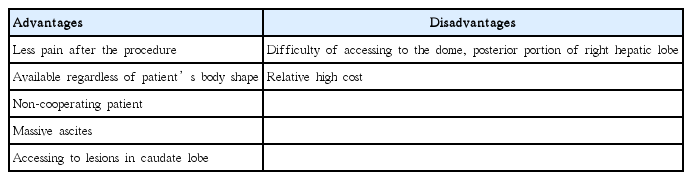

Although the anatomy limits EUS from getting access to the dome and posterior portions of the right hepatic lobe, EUS-FNB for HSM has a several advantages (Table 6). First, it may be less painful than the percutaneous approach, as it avoids skin puncture and eliminates breath-holding during the procedure, especially in elderly patients who might not be able to cooperate well. In our study, the median VAS score after the procedure was 1.76±0.68 and no analgesics were required. In contrast, several studies reported more than moderate pain requiring analgesics after percutaneous LB in 20% of the cases [2,14]. Second, it is a real-time image guided approach, in which one can visualize and avoid the bile duct or blood vessels <1 mm in size, thus minimizing the complication rate. In this present, hemorrhage after the procedure occurred in only one case (1.7%) and was well managed by endoscopic hemostasis using an endoclip. Our result are similar to other studies [15,16]. Third, the trans-gastric or trans-duodenal route for EUS-FNB is a reproducible approach, regardless of the patient body form or the anatomical difficulty resulting from interrupting a major vessel or a deep site in the body that might limit accessibility by US or CT-guided percutaneous needle puncture. The caudate lobe is anatomically difficult to access through the percutaneous approach. Massive ascites is also a relative contraindication for percutaneous LB, due to the short distance between the abdominal wall and the HSMs, and an increased risk of uncontrollable bleeding into the ascitic cavity. EUS-FNB can overcome both of these problems and is a good alternative for evaluating and diagnosing HSMs. In this study, EUS-FNB was performed in 9 patients for the histologic diagnosis of HSMs, due to poor access via the US or CT-guided approach. Fourth, there is no need for a vascular puncture or for placing a catheter through the heart, which is required in trans-jugular LB. Fifth, evaluation of the biliary tract, gallbladder, pancreas, regional lymph node or vascular structures during EUS-FNB concurrently allows a histologic confirmation of the primary malignancy or metastasis as well as cancer staging. Of the 58 cases who underwent EUS-FNB, 38 (65.5%) cases were simultaneously examined for a pancreatic mass, as well as HSMs, and were subsequently confirmed as pancreatic cancer with liver metastasis. In addition, EUS-guided palliative therapeutic treatment such as EUS-guided ethanol injection for small pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor might be used for metastatic HSMs [17].

Advantages and Disadvantages of Endoscopic Ultrasound Guided Fine Needle Biopsy Compared to Percutaneous Needle Biopsy for Hepatic Solid Masses

There are diagnostic limitations of the cytological evaluation with H&E staining alone using an HSM. In this setting, IHC has become a useful ancillary tool for distinction between different hepatic neoplasms. An initial antibody panel such as Hep Par 1, GPC 3, pCEA and MOC-31 and a second panel including CK 7, CK 19, CK 20 are commonly used for the differential diagnosis of HCC, CCC, and metastatic adenocarcinoma [18]. Furthermore, when metastatic adenocarcinoma is suspected, an additional site of possible origin can be examined using site-specific or cell-specific IHC markers. In our study, IHC stains on specimens with EUS-FNB were available in 53 cases (91.4%) which contributed to the high diagnostic accuracy. Interestingly, 3 patients were confirmed with neuroendocrine tumor by IHC stain.

There are no definitive reports comparing FNA and FNB in the literature [19,20]. A recent meta-analysis, comparing core biopsy needle with standard FNA needle showed that there was no significant difference between sample adequacy, diagnostic accuracy, or obtaining a core specimen [21]. However, Wittmann et al. [22] demonstrated that an improvement in the diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity was also observed when using a combination of FNB with FNA in pancreatic tumors. Combining EUS-FNB and FNA also increased the diagnostic accuracy without ROSE in gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors [23]. In our study, the diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity increased from 89.7% to 93.1%, and from 89.7% to 93.1, when using a combination FNB and cytology result without ROSE. Although the availability of ROSE has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy of EUS-guided sample acquisition, the number of institutions using ROSE is still limited [24]. Based on our results, EUS-FNB combined cytology results may be considered as a useful modality for histologic diagnosis on HSMs without ROSE, although further research is required to confirm this.

Another important finding of our study was that no significant predictors of diagnostic accuracy, including the mass size, needle type, route of puncture, and number of needle passes. A presumptive explanation may be that the procedure is highly dependent on the operator’s skill and that the interpretation of the obtained specimen by an expert pathologist is an important element in the diagnostic accuracy. In our study, a very experienced endosonologist performed all of the procedures, which may have contributed to the diagnostic accuracy. Moreover, a dedicated pathologist examined all the specimens obtained by EUS-FNB from HSMs, which may have contributed to the high diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, these results are probably due to the fact that we used core needle for EUS-FNB and the procedure was terminated after confirming that obtained specimens had sufficient whitish core tissues. Several studies using core needle for EUS-guided tissue acquisition showed that fewer needle passes achieved relatively high diagnostic accuracy with high histologic yield, compared to conventional needle techniques [25,26].

Theoretically, a larger bore needle can help to obtain more cytological core tissue from the target organ, despite the technically difficulty in handling the needle. Schulman et al. [27], who studied human cadaveric hepatic tissue, reported that the 22-G FNB needle was the most adequate for LB sampling. However, many studies showed that there was no correlation between needle size and diagnostic performance of EUS-FNA in solid lesions. In our study, the needle size was not related to the diagnostic accuracy for HSMs.

There are some limitations of this study. The sample size is relatively small (n=58) to be able to make a definitive conclusion and acceptable safety profiles. There might have been a failure in reporting minor complications of EUS-FNB due to the retrospective nature of the study. Additionally, we did not compare EUS-FNB with percutaneous LB.

In conclusion, EUS-FNB might be a feasible, safe, less painful, and accurate alternative method for the diagnosis of HSMs and there were no variable factors associated with the diagnostic accuracy. However, it might be difficult to use EUS-FNB as a routine diagnostic tool for HSMs, completely replacing percutaneous LB. Therefore, further evaluation to determine its safety and to establish proper indications for EUS-FNB for HSMs may be necessary.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University fund in 2019.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Tae Hyeon Kim

Data curation: Hyung Ku Chon, Keum Ha Choi, THK

Formal analysis: HKC, KHC, THK

Funding acquisition: HKC, KHC, THK

Investigation: HKC, KHC, THK

Methodology: HKC, KHC, THK

Project administration: HKC, KHC, THK

Resources: HKC

Software: HKC

Supervision: HKC, THK

Validation: HKC, THK

Visualization: HKC, Hee Chan Yang, THK

Writing-original draft: HKC, HCY, THK

Writing-review&editing: HKC, HCY, THK