Endoscopic Ultrasonography Findings for Brunner’s Gland Hamartoma in the Duodenum

Article information

Brunner’s gland hyperplasia is a benign proliferative disorder of Brunner’s gland in the duodenum, and it is frequently encountered in the duodenal bulb during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy [1]. Most lesions are small (≤5 mm). Brunner’s gland hamartoma (BGH) or adenoma is a rare duodenal tumor, which is usually larger (≥10 mm) than Brunner’s gland hyperplasia. BGH is considered benign with rare neoplastic transformation, and very few cases with focal neoplastic changes have been reported [2,3].

BGH is essentially a benign tumor, and an accurate diagnosis is important for preventing invasive therapeutic procedures, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgical resection, if the BGH does not cause any symptoms or complications. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is a useful non-invasive diagnostic modality. However, several researchers have reported characteristic EUS findings for BGH based on only a few cases, and they differ with the studies [4-6]. Therefore, in the present study, EUS findings specific to BGH and based on corresponding pathology results are described.

From 2000 to 2014, patients who underwent EUS (GF-UE260-AL5; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and were diagnosed with Brunner’s gland hyperplasia (≥10 mm) confirmed by pathology (Fig. 1) were identified from Myungji Hospital (Goyang, Korea) and Wonju Christian Hospital (Wonju, Korea). A tumor with a diameter of ≥ 10 mm was classified as BGH. Ten patients were included in this study. Patient data, such as EUS, endoscopy, computed tomography, and pathological findings, were evaluated, and the EUS findings were correlated with the pathology results. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Myungji Hospital.

Brunner's gland hamartoma or adenoma (hematoxylin & eosin stain, ×200). (A) Brunner's gland hamartoma is composed of a dilated cyst. (B) Hyperplasia of Brunner’s glands and fibrous stroma.

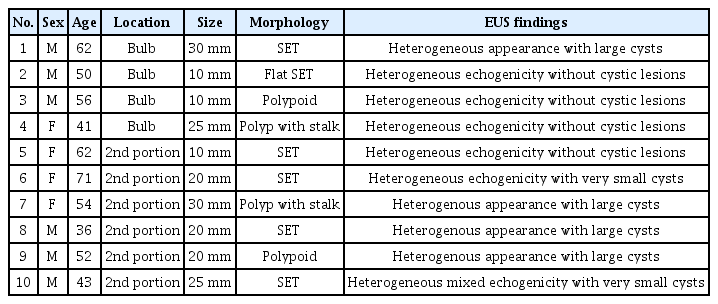

The clinical and pathological features, including the EUS findings, of the 10 patients were analyzed (Table 1). The mean age was 52.7 ± 10.7 years, and 6 (60%) patients were male. The diameter of the tumor ranged from 10 to 36 mm, and the median diameter was 26.3 mm. Nine (90%) patients were asymptomatic and diagnosed during health check-ups, but one (10%) had intermittent severe dyspepsia, which might have resulted from a large mass (35 mm) in the duodenal bulb. Of the 10 BGHs, 9 (90%) were removed by endoscopic resection, and 1 (10%) was resected using open laparotomy. The frequent EUS findings were as follows: the lesions (1) were located mainly in the submucosal layer, (2) had variable echogenicity, (3) were solid, large, or small cystic, and (4) were well-circumscribed. These EUS findings were arbitrarily classified into three groups based on the common findings: (1) heterogeneous appearance with large cysts (Fig. 2) in 4 (40%) patients; (2) heterogeneous echogenicity without cystic lesions (Fig. 3) in 4 (40%) patients; (3) heterogeneous mixed echogenicity with very small cysts (Fig. 4) in 2 (20%) patients. All BGHs were located in the submucosal or mucosal layer and were well-demarcated based on EUS.

(A) Endoscopy reveals a pedunculated polypoid mass in the duodenal bulb. (B) Endoscopic ultrasound reveals a heterogeneous appearance with an anechoic lesion representing cysts (red arrow). (C) On computed tomography, a round mass with a well-demarcated cystic lesion in the duodenal bulb is shown (red arrow). (D) Histological examination reveals the proliferation of Brunner's glands and fibrous stroma with several dilated cysts (blue arrow, hematoxylin & eosin stain, ×10).

(A) Endoscopy reveals a round sessile polypoid mass in the second portion of the duodenum (red arrow). (B) On endoscopic ultrasond, a heterogeneous hyperechoic appearance without anechoic lesions is shown (red arrow). (C) Histological examination reveals dense Brunner's gland proliferation without definite cystic lesions (hematoxylin & eosin stain, ×10)

(A) Endoscopy reveals a round sessile polypoid mass in the duodenal bulb. (B) Endoscopic ultrasound reveals a heterogeneous appearance, with tiny anechoic lesions representing cysts (red arrow). (C) On computed tomography, a homogeneous round mass in the duodenal bulb is shown (red arrow). (D) Histological examination reveals the proliferation of Brunner's glands and fibrous stroma without cystic lesions (hematoxylin & eosin stain, ×10).

Brunner’s glands are mucin-secreting and located in the submucosa of the duodenum. They were described by Brunner as “pancreas secundarium” in 1688 and re-named by Middendorf as Brunner’s gland in 1846 [7]. BGH is a benign tumor arising from the Brunner’s glands, and it was first described as Brunner’s gland adenoma by Curveilheir in 1835 [1]. BGH is a rare tumor with an estimated overall incidence of 0.008% based on a study of 215,000 autopsies [2], and it accounts for ≤5% of benign duodenal tumors [1]. The majority are pedunculated and 1-2 cm in size [8,9]. The pathogenesis of BGH remains unclear. BGH is mainly asymptomatic but occasionally causes nonspecific symptoms, gastrointestinal obstruction, or bleeding [8].

BGH is considered essentially benign. To the best of our knowledge, only three cases of BGH associated with neoplastic foci have been reported: a focus of glands with cellular and structural atypia [10], microcarcinoid foci [3], and foci of dysplasia with cytological changes. Therefore, BGH can be appropriately diagnosed using non-invasive diagnostic modalities and monitored without any manipulation if asymptomatic.

Several researchers have attempted to determine the typical EUS findings associated with BGHs, which are rarely atypical. Weisselberg et al. [4] reported that a large BGH had variable echogenicity and multiple large cysts within it on EUS. Matsushita et al. [5] reported that a heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion with small cystic areas was the typical EUS appearance of BGH. Hizawa et al. [6] reported that a heterogeneous solid or cystic mass within the submucosa was typically found in 6 cases on EUS. Changchien et al [11]. reported a heterogeneous hyperechoic pedunculated mass with several cystic lesions as the typical appearance. The EUS findings vary; however, common findings of BGH lesions include the following from the present study: (1) located mainly in the submucosal layer or extended to the mucosal layer; (2) variable echogenicity, hyperechoic, isoechoic, hypoechoic, or mixed; (3) solid, large, or small cystic; (4) round and well-circumscribed. These findings were classified into three categories (Fig. 2–4).

The various EUS findings are associated with different BGH histopathologies; the heterogeneous echogenicity is attributed to the fibrous stroma with bundles of smooth muscle in the tumor, the hypoechoic echogenicity is attributed to clusters of mucin-secreting glands, and the anechoic cystic areas are attributed to dilated glands and ducts or dilated vessels.

In summary, the EUS features and classification presented in the present study can help diagnose BGH non-invasively. EUS is a useful diagnostic method that informs the choice of treatment and monitoring approaches.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest:The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding:None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Kyong Joo Lee

Data curation: KJL

Investigation: Hee Man Kim

Methodology: HMK

Writing-original draft: Bonil Park

Writing-review & editing: HMK