Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy in the Diagnosis of Biliary and Pancreatic Disorders: A Systematic Analysis

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Endoscopic visualization of the microscopic anatomy can facilitate the real-time diagnosis of pancreatobiliary disorders and provide guidance for treatment. This study aimed to review the technique, image classification, and diagnostic performance of confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE).

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of CLE in pancreatic and biliary ducts of humans, and have provided a narrative of the technique, image classification, diagnostic performance, ongoing research, and limitations.

Results

Probe-based CLE differentiates malignant from benign biliary strictures (sensitivity, ≥89%; specificity, ≥61%). Needle-based CLE differentiates mucinous from non-mucinous pancreatic cysts (sensitivity, 59%; specificity, ≥94%) and identifies dysplasia. Pancreatitis may develop in 2-7% of pancreatic cyst cases. Needle-based CLE has potential applications in adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and pancreatitis (chronic or autoimmune). Costs, catheter lifespan, endoscopist training, and interobserver variability are challenges for routine utilization.

Conclusions

CLE reveals microscopic pancreatobiliary system anatomy with adequate specificity and sensitivity. Reducing costs and simplifying image interpretation will promote utilization by advanced endoscopists.

INTRODUCTION

Endomicroscopy refers to the use of different imaging technologies to microscopically evaluate the epithelium in real time. Electronic spectral enhancement and topical dyes are used to evaluate mucosal changes and identify superficial gastrointestinal neoplasia. Technologies such as narrow band imaging (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan), iScan (Pentax Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and blue light/blue laser imaging (Fujinon Intelligent Chromo Endoscopy, Fujinon, Saitama, Japan) help separate the areas of metaplasia, dysplasia, and early neoplasia from normal mucosa in the gastroesophageal junction, stomach, and colon [1]. With a higher magnification power, optical coherence tomography and volumetric laser endomicroscopy provide images of different histologic layers and cellular changes of the gastrointestinal epithelium and are useful for evaluating Barrett’s esophagus [2]. The diameters of the biliary and pancreatic ducts in normal conditions are significantly smaller than the rest of the gastrointestinal tract, making the evaluation of the biliary epithelium and pancreatic parenchyma particularly challenging using conventional optical devices.

Confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE) uses intravenous fluorophore, fluorescein, and a fiber-optic confocal laser to achieve higher magnification and reveal cellular and subcellular structures in the epithelium (Fig. 1). Multiple applications of CLE have been described across gastrointestinal luminal neoplasia, including increasing the detection of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus, categorizing early gastric cancer, identifying dysplasia associated with inflammatory bowel disease, and revealing early cancer in colon polyps or surgical margins [3–6]. CLE has also been evaluated in benign conditions, including identifying mucosal atrophy in gastritis, measuring vascular integrity in celiac disease, determining mucosal permeability in inflammatory bowel disease, and visualizing inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome [7–11].

Comparison of available endomicroscopy imaging technologies. FICE, Fujinon Intelligent Chromo Endoscopy (Fujinon, Saitama, Japan); HD, hight definition; iScan (Pentax Inc., Tokyo, Japan)); NBI, narrow band Imaging (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan); OCT, optical coherence tomograpy; VLE, volumetric laser endomicroscopy. Courtesy of Dr. Wallace MB.

Small-caliber CLE catheters are introduced into the biliary and pancreatic structures through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Malignant biliary strictures are traditionally evaluated using a combination of cross-sectional imaging, cytology brushings, and biopsies with micro forceps. Pancreatic cysts are characterized using a combination of cross-sectional imaging, EUS, and fluid analysis. However, this approach has some limitations, particularly in chronic inflammatory conditions such as primary sclerosing cholangitis [12,13]. Over the last 20 years, interest has grown in using CLE imaging during endoscopy to facilitate evaluation of the biliary and pancreatic structures. This structured review aims to provide a clinical assessment of current applications of CLE in biliary and pancreatic disorders, summarize diagnostic performance in both areas, and present the most recent criteria for image interpretation.

METHODS

The literature databases PubMed (US National Library of Medicine), Cochrane (The Cochrane Collaboration), and ClinicalTrials.gov (US National Institutes of Health) were reviewed. The search was performed in PubMed using two queries: Confocal microscopy (Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] term) OR Confocal laser scanning microscopy (MeSH) AND Endoscopy (non-MeSH) AND Pancreas (non-MeSH); and Confocal microscopy (MeSH) OR Confocal laser scanning microscopy (MeSH) AND Endoscopy (non-MeSH) and Biliary (non-MeSH). The selected studies were limited to those including humans and those in the English language published through March 15, 2021. Analogous strategies were used to search the other two databases.

Two investigators, Do Han Kim and Paul T. Kröner, independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles. For journal manuscripts, full-text articles were retrieved for further review. Titles that could not be associated with an abstract were excluded from review. All studies and case reports that addressed the CLE technique, image interpretation or classification, accuracy estimations (i.e., specificity and sensitivity), interobserver agreement, and consensus meetings were retrieved and reviewed individually. Studies that used biomarkers or imaging tests other than CLE (e.g., EUS, cytology) as the main diagnostic tool were removed. If two or more manuscripts studied the same patient population, the one published most recently or with the largest sample was selected. If two manuscripts provided complementary information (e.g., different years), both were included. If there was any discrepancy about whether a study should be included, a third investigator (Juan E. Corral) determined adequacy. When needed, the corresponding authors of the studies were contacted for additional information.

The following information was abstracted from each article: year of publication, first author, sample size, comparison groups, diagnostic accuracy, and adverse events (e.g., pancreatitis). Using the available information, we analyzed sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy using conventional 2×2 tables.

We provide individual estimates of accuracy and opted not to perform a meta-analysis to illustrate the diversity of applications across different pathologies and patient subgroups. Furthermore, six meta-analyses have already been published on this topic, and their relevant results are included here [14–19].

RESULTS

The initial literature search retrieved 47 publications in the biliary group and 25 publications in the pancreas group. A Cochrane search retrieved CLE applications in dermatology (i.e., evaluation of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma) and ophthalmology (i.e., evaluation of the optic nerve and glaucoma) but no applications in gastroenterology. A review of ClinicalTrials.gov identified 20 trials using CLE in the biliary ducts and 10 trials using CLE in the pancreas.

After the exclusion of 14 irrelevant publications and three duplicate publications (overlapping pancreatic and biliary duct evaluation), 55 full-text articles were subjected to further evaluation. Numbers in Fig. 2, may differ considering that review articles covered both pancreatic and biliary, studies found in Clinical trials.gov not included. No studies were excluded for having a small sample size (Fig. 2).

Literature review flowchart. MeSH, medical subject headings used by the National Library of Medicine.

CLE Technique

Thin confocal laser probes feature a small enough diameter to allow their insertion through the working channel of conventional endoscopes and advancement through endoscopy needles. These techniques allow navigation into the biliary and pancreatic ducts and evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions. Imaging depth can be carefully controlled with fluoroscopy by a single operator.

Two commercial probes are now available, one of which has been cleared by the United States Food and Drug Administration for patient care (Cellvizio, Mauna Kea Technologies, Paris, France) [11]. Similar to other confocal applications, fluorescein (2–5 mL; 10% fluorescein sodium) is injected intravenously 2–3 minutes before imaging. Images are obtained placing the probe directly against the mucosa. The probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy (pCLE) probe or “miniprobe” works through a 1-mm compatible operating channel. It was designed to be inserted through a side-viewing endoscope into the biliary ducts. The needle-based confocal laser endomicroscopy (nCLE) probe is slightly thinner and works through a compatible 0.95-mm operating channel. It was designed to be advanced through a 19-gauge EUS needle into pancreatic cysts.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, both probes can be used up to 10 times. The probe tip is radio-opaque, allowing guidance and probe positioning under fluoroscopy. The optical penetration of the confocal plane provides superficial subsurface information without interference from bile or solid residues. Images feature high resolution at the cellular level. For both pCLE and nCLE, the manufacturer reports a field of view of 325 μm, resolution of 3.5 μm, and confocal depth of 40–70 μm. Changes in the tissue micro-architecture are used to visually differentiate between malignant and benign disorders (Fig. 1). Training for image recognition and interpretation takes approximately 6 hours for pCLE and 5 hours for nCLE [20,21]. Three main applications were identified in our systematic review: indeterminate biliary strictures, pancreatic cysts, and pancreatic parenchyma.

Indeterminate biliary strictures

Malignant biliary strictures (caused by cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, or metastatic cancer to the liver) can be difficult to differentiate from benign strictures (caused by inflammation, surgical scaring, or extrinsic compression). Up to 15% of patients who undergo surgical resection for suspected malignancy end up having a benign condition [22].

When a biliary stricture is identified, the conventional approach is ERCP with bile duct brushings for cytology, fluorescence in-situ hybridization analysis for trisomy/polysomy, and cholangioscopy with targeted biopsies for histology. This triple approach has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 96% for identifying cancer [23]. In these patients, pCLE is an adjunct tool for differentiating benign from malignant biliary strictures. Once the biliary stricture is located by the injection of radiopaque contrast, the pCLE catheter is passed through the narrow area while a black and white histology video is recorded. Images can be interpreted in real time or reviewed later by freezing frames for better interpretation. After pCLE videos are collected, the conventional brushings and biopsies can be performed.

Diagnostic criteria and performance

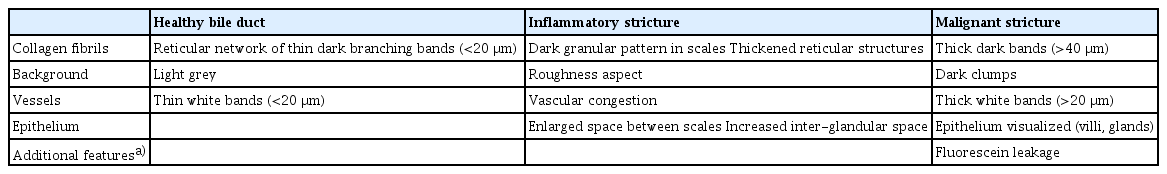

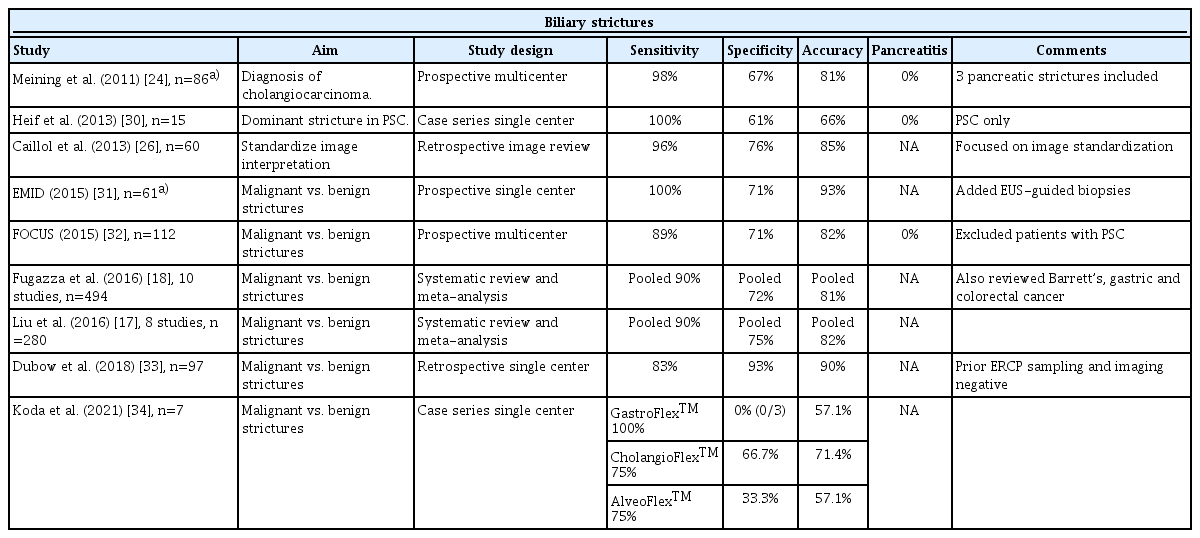

Image interpretation of pCLE is based on bands, shadows, and background colors that reflect changes in vascular patterns and epithelial cells. White bands correspond to lymphatic or blood vessels, while dark bands correspond to collagen fibrils that clump into tumoral glands [24]. An expert meeting proposed the initial criteria for the interpretation of CLE biliary images in 2011 (Miami classification) [25]. Two years later, a second meeting refined the criteria and increased their specificity and accuracy (Paris classification; Table 1) [26]. In this system, the bile ducts are classified as normal, inflammatory strictures, or malignant strictures (Fig. 3).

Representative patterns of probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy in biliary ducts conditions. Courtesy of Mauna Kea Technologies, Inc.

An international consensus in 2015 reported that pCLE is more accurate than ERCP with brush cytology and/or forceps biopsy for discriminating malignant from benign strictures using established criteria (87% agreement) [27]. ERCP-guided pCLE is now mentioned as an adjunct tool by the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy for management of patients with indeterminate biliary strictures [28]. A technical review from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recognized that pCLE is currently difficult and expensive but has the potential to become an important diagnostic tool for indeterminate biliary strictures [29].

The diagnostic performance of pCLE in indeterminate biliary strictures is demonstrated in Table 2. Among the 46 publications identified in the literature, nine were considered relevant. Sensitivity ranged from 75% to 100% and specificity ranged from 0% (one small study with three participants) to 93%. Overall, pCLE has a great negative predictive value for cancer in indeterminate biliary strictures. The negative predictive value of pCLE was estimated to be 94%, those of biliary biopsies (78%), biliary brushings (77%), and ERCP overall (98%) [33]. In fact, pCLE has additional value for patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), who experience progressive inflammation of the bile ducts and develop cholangiocarcinoma at high rates (1.5% incidence per year). Distinguishing cholangiocarcinoma from other inflammatory strictures in PSC remains challenging. Compared to other indications, the sensitivity of the traditional triple approach (fluorescence in-situ hybridization, cytology brushings, and biopsies) in PSC is only 54%, but it increases to 61% after the addition of pCLE (specificity and accuracy remain >80%, while the negative predictive value is 100 [95% confidence interval, 71.3–100]) [30].

Pancreatic cysts

Pancreatic cysts are easily visualized with EUS, and special needles are introduced into them to collect fluid for tumor marker and cytology testing. Once a 19-gauge needle is inserted into a pancreatic cyst, an nCLE probe is advanced under EUS guidance into the pancreatic cyst. An intracystic endomicroscopic video is captured with permissive angulation of the needle facilitated by the elevator of the ecoendoscope using axial rotation of the endoscopist or the gentle application of torque. After the image collection, the nCLE probe is withdrawn and the cyst can be aspirated. The cystic fluid is evaluated for cytology, amylase, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels, mutations in tumor suppressor genes (loss of heterozygosity), and oncogene point mutations. If desired, a small-caliber biopsy forceps (Moray micro forceps, US Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio, USA) can also be advanced through the needle channel to enable additional biopsies of the cyst wall [44]. At the end of the procedure, intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis is administered to prevent cyst infection.

Of note, using the same technique as for bile duct evaluation, a pCLE probe can be introduced into the pancreatic duct for the evaluation of malignant pancreatic strictures or main duct–intraductal mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) [24].

Diagnostic criteria and performance

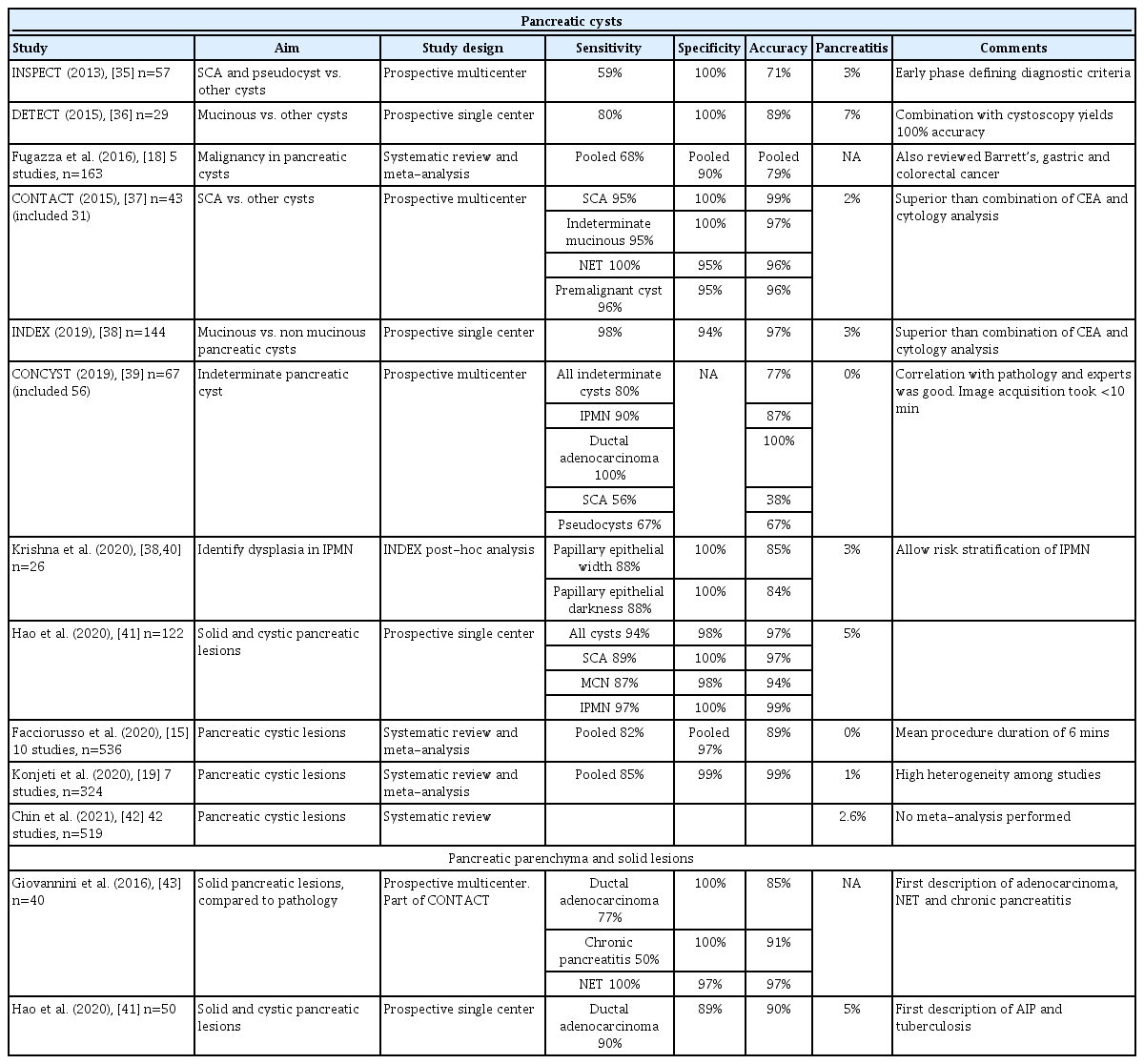

It is noteworthy that nCLE was not reviewed at the consensus meeting in 2015 or the most recent European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy technology review [27,29]. The 2016 American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline for managing cystic pancreatic neoplasms acknowledged that the addition of nCLE increases the diagnostic yield of serous cystic neoplasms with high interobserver agreement [45]. Landmark studies evaluating nCLE in pancreatic cysts and solid lesions are shown in Table 3.

Landmark Studies Evaluating Needle-based Confocal Endomicroscopy in Pancreatic Cysts and Solid Lesions

Comprehensive diagnostic criteria for nCLE in the evaluation of pancreatic cysts were established in the CONTACT and the INDEX studies [37,38,40]. Its diagnostic features are divided into epithelial patterns and vascular patterns (Table 4 [36,38]). Specific patterns for different types of pancreatic cysts are shown in Fig. 4. The addition of nCLE can enable the classification of pancreatic cysts into mucinous cysts (IPMN or mucinous cystic neoplasms) and non-mucinous cysts (serous cystadenoma, pseudocyst, or solid tumors with a cystic component [e.g. neuroendocrine tumors]). A clear application of nCLE is identifying benign serous cystadenomas and thereby preventing unnecessary surgery in these patients. A recent study showed that nCLE can be used to identify dysplasia and localized cancer in cases of IPMN. After the implementation of the INDEX criteria, papillary width and darkness should be measured (Table 4) [40].

Representative patterns of needle-based confocal laser endomicroscopy in pancreatic cysts. Pseudocyst can have a dark or light background. Cystic NET and SPT can only be differentiated using immunostaining. IPMN, intraductal mucinous papillary neoplasm; MCN, mucinous cystic neoplasm; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; SCA, serous cystadenoma; SPT, solid pseudopapillary tumor. Courtesy of Krishna SG.

Studies initially raised concerns that the addition of nCLE to the traditional EUS aspiration of pancreatic cysts would increase the rate of adverse events (reported in 7–9% of all cases) [46]. However, larger studies published over the last 10 years show reduced rates of pancreatitis similar to those seen for ERCP (Table 2). Other adverse events include bleeding into the cyst (1%), pruritus (1.5%), pseudocyst infection (1.5%; one case reported resolved with antibiotics), and peri-pancreatic fluid collection (2%) [41,47].

Pancreatic parenchyma

Two studies have evaluated the use of nCLE for the pancreatic parenchyma and solid tumors [41,43]. Researchers in China and France described the general characteristics of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumors, chronic pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, solid pseudopapillary tumors, and one case of pancreatic tuberculosis (Table 5 [40,42]). The reported performance and pancreatitis incidence was similar to that reported for nCLE for pancreatic cysts (Table 3). In the authors’ experience, without the liquid interface of the cyst, images are static and image interpretation is challenging.

DISCUSSION

Implementation costs, catheter lifespan, sampling errors, interobserver variability, and added procedure time have limited the broader utilization of CLE in clinical practice [48]. While CLE technology is being refined, alternative devices for tissue acquisition have been developed [49]. For pancreatic cysts, micro forceps allow tissue sampling under direct EUS visualization. The risk of developing pancreatitis from an nCLE evaluation is similar to or lower than that of biopsies performed using micro forceps (2.1%) [49]. The most cited limitation of both pCLE and nCLE is disagreement among expert endoscopists on image interpretation. Agreement was rated “poor” to “good” in three studies [20,50,51]. Artificial intelligence systems have significant potential to resolve this issue.

Our review of ClinicalTrials.gov identified five clinical trials recruiting patients to receive CLE: three in China, one in Brazil, and one multicenter study in the United States. Two trials will evaluate patients with pancreatic cysts, two with patients requiring surgery (or percutaneous drainage) after pancreatic trauma, and one will utilize CLE for the early detection of different gastrointestinal tumors (Barrett’s esophagus, partial gastric antrectomy, biliary duct strictures, pancreatic duct strictures, colorectal polyps, esophageal neoplasms, pancreatic head, and neck tumors). Significant limitations were found in studies evaluating its use for the pancreatic parenchyma or solid lesions.

Finally, early studies show that implementing deep learning algorithms into image recognition can facilitate CLE interpretation and expediate the clinical diagnosis [52,53]. Despite the advances identified in our review, few studies have demonstrated that the use of CLE can change clinical decisions (e.g. prevent surgery) or improve direct patient care (e.g. shorten time to surgery or chemotherapy) [37]. Prospective trials able to prove such benefits will be instrumental in justifying the added cost of implementing CLE in regular clinical practice.

In conclusion, pCLE and nCLE enable the microscopic evaluation of the bile ducts and pancreas in vivo and in real time, enhancing the imaging arsenal of gastroenterologists. Integrating CLE into the endoscopy room along with conventional cytology, histology, and molecular testing improves cancer detection. Although our understanding of CLE microscopy continues to increase, patient outcomes data remain limited. CLE images remain subject to significant inter-reader reliability and sampling errors. Despite those limitations, most experts agree on the potential of CLE imaging and support its integration into future diagnostic algorithms [26,32].

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

Juan E. Corral: Travel grant from AbbVie, Inc.; Minor food and beverage from Boston Scientific and Cook Medical.

Emmanuel Coronel: Consulting for Boston Scientific.

Michael B. Wallace: Consulting for Virgo Inc, Cosmo/Aries Pharmaceuticals, Anx Robotica (2019), Covidien, and GI Supply; Research grants from Fujifilm, Boston Scientific, Olympus, Medtronic, Ninepoint Medical, Cosmo/ Aries Pharmaceuticals; Stock options from Virgo Inc; Consulting on behalf of Mayo Clinic, GI Supply (2018), Endokey, Endostart, Boston Scientific, and Microtek; General payments/minor food and beverage from Synergy Pharmaceuticals, Boston Scientific, and Cook Medical.

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding: None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Juan E. Corral

Data curation: Do Han Kim, Emmanuel Coronel, Paul T. Kröner

Formal analysis: DHK, EC, PTK

Funding acquisition

Investigation: DHK, EC, PTK

Methodology: JEC

Project administration: JEC

Resources: JEC

Supervision: JEC

Validation: Herbert C. Wolfsen, Michael B. Wallace

Visualization: Somashekar G Krishna, MBW

Writing-original draft: JEC

Writing-review & editing: DHK, HCW, MBW

Acknowledgements

JEC: Travel grant from AbbVie, Inc.; Minor food and beverage from Boston Scientific and Cook Medical.

EC: Consulting for Boston Scientific.

MBW: Consulting for Virgo Inc, Cosmo/Aries Pharmaceuticals, Anx Robotica (2019), Covidien, and GI Supply; Research grants from Fujifilm, Boston Scientific, Olympus, Medtronic, Ninepoint Medical, Cosmo/Aries Pharmaceuticals; Stock options from Virgo Inc; Consulting on behalf of Mayo Clinic, GI Supply (2018), Endokey, Endostart, Boston Scientific, and Microtek; General payments/minor food and beverage from Synergy Pharmaceuticals, Boston Scientific, and Cook Medical.