Significance of rescue hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection in difficult colorectal cases

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), in which an incision is made around a lesion and snaring is performed after submucosal dissection, has some advantages in colorectal surgery, including shorter procedure time and preventing perforation. However, its value for rescue resection in difficult colorectal ESD cases remains unclear. This study evaluated the utility of rescue hybrid ESD (RH-ESD).

Methods

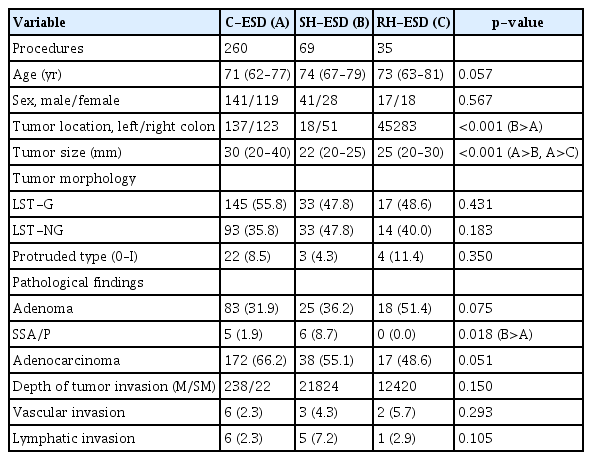

We divided 364 colorectal ESD procedures into the conventional ESD group (C-ESD, n=260), scheduled hybrid ESD group (SH-ESD, n=69), and RH-ESD group (n=35) and compared their clinical outcomes.

Results

Resection time was significantly shorter in the following order: RH-ESD (149 [90–197] minutes) >C-ESD (90 [60–140] minutes) >SH-ESD (52 [29–80] minutes). The en bloc resection rate increased significantly in the following order: RH-ESD (48.6%), SH-ESD (78.3%), and C-ESD (97.7%). An analysis of factors related to piecemeal resection of RH-ESD revealed that the submucosal dissection rate was significantly lower in the piecemeal resection group (25% [20%–30%]) than in the en bloc resection group (40% [20%–60%]).

Conclusions

RH-ESD was ineffective in terms of curative resection because of the low en bloc resection rate, but was useful for avoiding surgery.

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), it has become possible to resect large lesions and lesions with ulcer scars that cannot be resected en bloc using conventional endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).1-3 Compared with EMR, ESD has a higher en bloc resection rate and lower recurrence rate. It is also currently established as a minimally invasive treatment for early stage gastrointestinal cancers.4-6 However, aside from being difficult and longer to perform, ESD carries a high risk of intraoperative perforation.7-9 Currently, there is growing interest in hybrid colorectal ESD, where an incision is made around the lesion and snaring is performed after submucosal dissection to compensate for the shortcomings of ESD.10,11 Hybrid ESD has some advantages, including shorter procedure time and lower risk of perforation. However, it is unclear whether unplanned hybrid ESD by snaring is useful in cases that are difficult to treat by conventional ESD (C-ESD), such as those with unexpected perforation or fibrosis. This study aims to evaluate the utility of rescue hybrid ESD (RH-ESD) in difficult-to-treat colorectal cancer cases.

METHODS

Patients

A total of 380 lesions from 374 patients who underwent ESD or hybrid ESD between December 2012 and April 2021 at Tokyo Medical University Hospital were retrospectively analyzed. Fifteen lesions from 15 patients with neuroendocrine tumors and a lesion from one patient with mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma were excluded. Thus, the total number of samples included in the analysis is 364 superficial colorectal neoplasms from 358 patients who underwent ESD or hybrid ESD. We divided the 364 colorectal ESD or hybrid ESD procedures into the C-ESD group (n=260), scheduled hybrid ESD (SH-ESD) group (n=69), and RH-ESD group (n=35) according to the type of procedure performed (Fig. 1). We compared the clinical outcomes, including endoscopic findings, technical results, adverse events, and histopathological results, among the groups.

Indications for ESD and hybrid ESD

ESD was indicated for colorectal neoplasms that met the following criteria: en bloc resection with snare EMR was anticipated to be too difficult (such as a laterally spreading tumor–non-granular type lesion, a lesion with a Vi-type pit pattern, carcinoma with shallow submucosal invasion, a large depressed-type tumor, and large protruded-type lesion suspected to be carcinoma); mucosal tumor with submucosal fibrosis; sporadic tumor on a background of chronic inflammation, such as ulcerative colitis; and local residual or recurrent early carcinoma after endoscopic resection. Lesions suspected to have invaded deep into the submucosal or muscular layer were not considered amenable to ESD.

The indications for hybrid ESD were as follows: cases in which access to the lesion was difficult because the lesion was front-facing, such as a cecal lesion or tumor diameter ≤40 mm, and need for a short treatment time, particularly in very elderly patients and those with serious underlying disease. Two weeks before the endoscopic procedure, a meeting was held in our endoscopy room to determine whether to perform C-ESD or SH-ESD for a given colorectal neoplasm.

Endoscopic resection procedure

Conventional and hybrid ESD procedures were performed in an endoscopy room with the patient induced under local anesthesia, which was maintained by regular intravenous administration of midazolam. C-ESD was performed using the following standard procedure. A tip attachment (D-2201-11304; Olympus Medical Systems) mounted on an endoscope (GIF-260J, GIF-290T, PCF-Q260JI, or PCF-290TI; Olympus Medical Systems), ESD knife (ITknife nano or DualKnife; Olympus Medical Systems), and high-frequency electrosurgical system (VIO-300D; Erbe Elektromedizin) were used. The high-frequency settings were set to ENDO CUT 1 Effect 3 for mucosal incision and Swift Coag Effect 3 (30 W) for submucosal dissection. A mixture of 0.4% sodium hyaluronate solution (MucoUp; Seikagaku Corp.) and glycerol solution with a small amount of indigo carmine was injected locally into the submucosa. The area outside of the lesion was then incised, and the lesion was resected en bloc via submucosal dissection with an ESD knife.

Hybrid ESD is a procedure in which an incision is made around the lesion and snaring is performed after submucosal dissection. SH-ESD was performed as follows (Fig. 2, Supplementary Video 1). As in C-ESD, after the local injection of the submucosa, a full circumferential incision was made outside the lesion. The submucosal layer was then dissected with an ESD knife until it was sufficiently large to be safely resected en bloc with a snare. If the snaring was inadequate, the ends of the lesion might change in shape, resulting in residual lesions; therefore, the submucosal layer was peeled off and trimmed until the snare could slide under the lesion. After adequate submucosal dissection, local injection was administered in the submucosa. Next, the tip of the snare (SnareMaster; Olympus Medical Systems) was placed on the mouth side of the lesion, which was then slowly opened to prevent the tip from shifting, and the lesion was strangulated for final resection. If perforation occurred during ESD, it was closed using EZ clips (HX-610-090; Olympus Medical Systems).

Sample scheduled hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure. (A) A 30-mm flat elevated lesion located in the cecum. (B) After the injection of a mixture of 0.4% sodium hyaluronate solution, glycerol solution, and indigo carmine into the submucosal layer, a full circumferential incision was made outside the lesion. The submucosal layer was then dissected with an endoscopic submucosal dissection knife until it was large enough to be safely resected en bloc with a snare. (C, D) After adequate submucosal dissection, a local injection was administered in the submucosal layer, and the tip of the snare was placed on the mouth side of the lesion. The snare was then slowly opened to prevent the tip from shifting, and the lesion was strangulated for final resection.

For lesions that were difficult to resect, after a local injection was administered to the submucosa, RH-ESD was performed by snaring the lesion in the middle of the dissection (Fig. 3, Supplementary Video 2). Indications for RH-ESD in difficult colorectal cases include intraoperative perforation, long procedure time likely due to severe fibrosis, and emergency situations where the patient has unstable vital signs during ESD. Follow-up colonoscopy after endoscopic resection was performed approximately 1 year after complete resection and approximately 6 months postoperatively for histologically positive resection margins. Thereafter, surveillance endoscopy is performed annually.

Sample rescue hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure. (A) Perforation that occurred during conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection. (B) Case with perforation in which endoclips were used for closure. (C, D) Because of the length of time taken for the treatment, a local injection was administered after submucosal dissection and snaring was performed for the lesion during dissection.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests. Fisher exact test or the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The procedure time was recorded, and the area of the submucosa dissected per unit time (mm2/min) was calculated by dividing the dissection time by the size of the resected specimen. The size of the specimens was calculated using the formula π×A×B/4, where A is the larger diameter and B is the smaller diameter. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (ver. 28.0; IBM Corp.). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Ethical statements

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Medical University Hospital (study approval number: T2020-0098) and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards described in the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained via an opt-out method, with a notice posted at Tokyo Medical University Hospital.

RESULTS

Patient and lesion characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The median age was 71 (interquartile range [IQR], 62–77) years in the C-ESD group, 74 (67–79) years in the SH-ESD group, and 73 (63–81) years in the RH-ESD group. The sex distribution (male/female) was 141/119, 41/28, and 17/18, respectively. There were no significant between-group differences in age or sex. Tumor diameter was significantly larger in the ESD group (30 [20–40] mm) than in the SH-ESD (22 [20–25] mm) and RH-ESD (25 [20–30] mm) groups (p<0.001). There were no significant differences in tumor morphology (laterally spreading tumor–granular type [145/33/17] vs. laterally spreading tumor–non-granular type [93/33/14] vs. protruded type [22/3/4]) in the C-ESD, SH-ESD, and RH-ESD groups). Adenoma was diagnosed in 83/25/18 lesions, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps in 5/6/0 lesions, and adenocarcinoma in 172/38/17 lesions in the C-ESD, SH-ESD, and RH-ESD groups, respectively. Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps were significantly more common in the SH-ESD group than in the C-ESD group (p<0.001).

Outcomes of endoscopic resection

The clinical characteristics of the patients are shown according to treatment response in Table 2. The en bloc resection rate increased significantly in the following order: RH-ESD (48.6%, 17/35), SH-ESD (78.3%, 54/69), and C-ESD (97.7%, 254/260; p<0.001). The horizontal margin positivity rates were 5.4% (14/260) in the C-ESD group, 2.9% (2/69) in the SH-ESD group, and 2.9% (1/35) in the RH-ESD group; the respective vertical margin positivity rates were 3.1% (8/260), 0% (0/59), and 2.9% (1/35). The submucosa invasion rates were 8.4% (22/260), 14.5% (10/69), and 2.9% (1/35) in the ESD, SH-ESD, and RH-ESD groups, respectively, and the lymphatic invasion rates were 2.3% (6/260), 10.1% (7/69), and 2.9% (1/35), respectively. The vascular invasion rates were 2.3% (6/260), 4.3% (3/69), and 5.7% (2/35) in the C-ESD, SH-ESD, and RH-ESD groups, respectively. There were no significant differences in the margin positivity rate, tumor depth, or lymphatic and vascular invasion rates among the three groups. The median size of the resected specimen was significantly larger in the C-ESD group (727 [446–1,241] mm2) than in the SH-ESD group (377 [254–528] mm2) and RH-ESD group (467 [245–692] mm2) (p<0.001). Resection time decreased significantly in the order of RH-ESD (149 [90–197] minutes) >C-ESD (90 [60–140] minutes) >SH-ESD (52 [29–80] minutes) (p<0.001). The perforation rate was 3.8% (10/260) in the C-ESD group, 2.9% (2/69) in the SH-ESD group, and 5.7% (2/35) in the RH-ESD group; the respective delayed bleeding rates were 3.8% (10/260), 7.2% (5/69), and 5.7% (2/35). Of the seven cases of perforation in the RH-ESD group, five occurred during ESD and required RH-ESD, one occurred due to the tip of the snare during snaring in RH-ESD, and one occurred during clip closure at the base of the ulcer after RH-ESD. In total, 216 lesions were monitored during follow-up by endoscopy after resection (median follow-up duration, 23 months [IQR, 12–39] months). The local recurrence rates were 0.7% (1/150) in the C-ESD group, 2.4% (1/42) in the SH-ESD group, and 4.2% (1/24) in the RH-ESD group; the differences were not statistically significant. None of the patients in the three groups underwent surgery due to local recurrence. One patient in the C-ESD group, two in the SH-ESD group, and three in the RH-ESD group underwent surgery due to piecemeal resection.

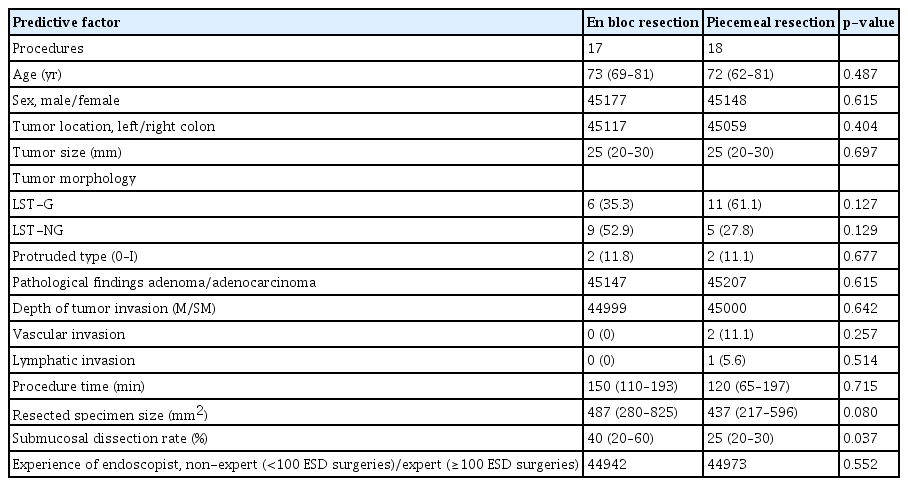

The predictive factors for piecemeal resection of RH-ESD are shown in Table 3. RH-ESD was categorized according to whether the resection was en bloc (n=17) or piecemeal (n=18). The submucosal dissection rate was significantly lower (p=0.037) in the piecemeal group (25% [20%–30%]) than that in the en bloc group (40% [20%–60%]). There were no significant differences in tumor size, morphology, lymphovascular invasion rate, tumor depth, or endoscopist experience between patients who underwent piecemeal resection and those who underwent RH-ESD.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the en bloc resection rate was significantly lower for RH-ESD than for C-ESD or SH-ESD. Therefore, RH-ESD cannot be considered as an effective curative treatment. However, the local recurrence rate was relatively low, and all local recurrences could be controlled with additional EMR or hot biopsy. Therefore, from a practical standpoint, RH-ESD may be clinically useful for avoiding surgery in cases of unsuccessful C-ESD despite its low curative resection rate.

The submucosal dissection rate of RH-ESD was significantly higher in the en bloc resection group than that in the piecemeal resection group (40% vs. 25%). In hybrid ESD, a snare may slip if the submucosal dissection surface is inadequate. Therefore, a smaller resection surface that considers the endoscopist's snaring technique is required. Preplanned SH-ESD allows for a high en bloc resection rate and a short procedure time. On the other hand, RH-ESD is only appropriate in difficult-to-treat cases, such as those in prolonged procedure time, perforated lesions, and inadequate submucosal dissection, and a large resection surface. These factors were also associated with a reduced en bloc resection rate. Previous reports have identified that a submucosal dissection rate of ≤50% is a risk factor for piecemeal resection.12 Previous studies have reported that the endoscopist’s level of experience affects the resection rate and frequency of adverse events in colorectal endoscopic treatment.13,14 However, there was no significant difference in the level of experience of endoscopists between the en bloc resection group and the piecemeal resection group in this study. Additionally, RH-ESD may result in piecemeal resection regardless of the endoscopist’s experience. When performing hybrid ESD, it is important to remove as much of the submucosal layer as possible and perform snaring under a good field of view to avoid piecemeal resection. In this study, the tumor diameter was significantly greater in the ESD group than in the SH-ESD and RH-ESD groups (30 [11–110] mm vs. 22 [11–45] mm and 25 [10–60] mm). Colorectal tumors can be resected en bloc using ESD regardless of size.15,16. However, with hybrid ESD, resection with a snare is difficult in larger tumors. Previous reports indicate that hybrid ESD is safe for tumors measuring 20 mm to 30 mm and is noninferior to C-ESD in terms of en bloc resection rate.17,18 However, it has been reported that the en bloc resection rate is lower with hybrid ESD than with C-ESD when lesions are >20 mm.19,20 Therefore, the tumor size should be considered when performing hybrid ESD.

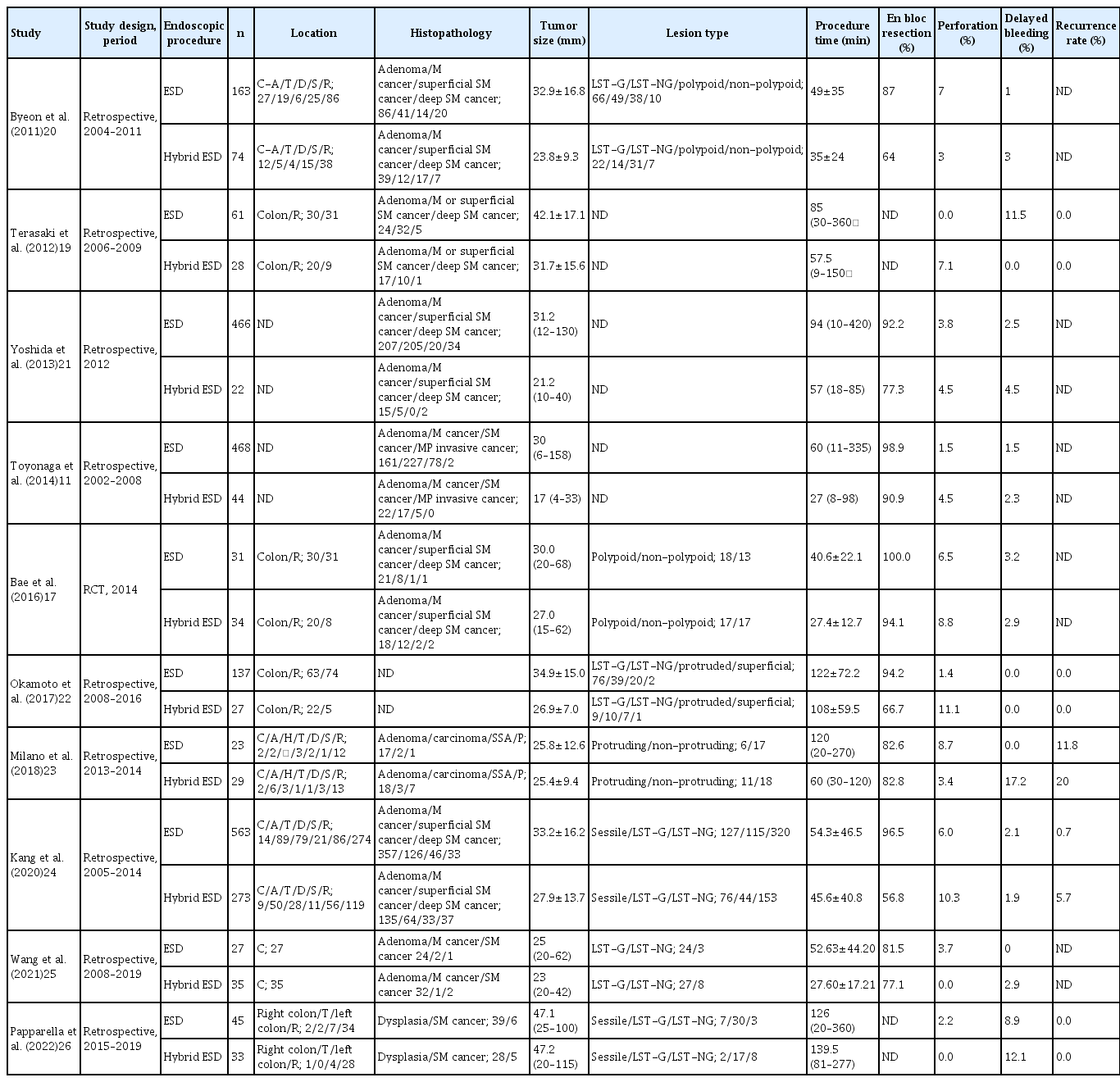

Previous reports on the clinical outcomes of hybrid ESD and C-ESD for colorectal lesions are summarized in Table 4.11,17,19-26 Although several studies have shown that the en bloc resection rate is significantly lower with the use of hybrid ESD techniques (56.8%–94.1%) than with the use of C-ESD techniques (81.5%–100%), most did not classify hybrid ESD into preplanned SH-ESD and unplanned RH-ESD.18-20,22 In general, planned SH-ESD is used for relatively small tumors that can be easily snared, whereas unplanned RH-ESD is used for lesions that are difficult to resect. Therefore, grouping these two techniques together may introduce bias into the previous study results. In the present study, the en bloc resection rate was lower than that of SH-ESD when RH-ESD was performed as a salvage procedure. Thus, when considering the use of hybrid ESD, SH-ESD should be planned preoperatively. In most published studies, the procedure time was significantly shorter with hybrid ESD than with C-ESD.11,19-21 In our study, the procedure time was significantly shorter for SH-ESD than C-ESD. Bae et al.17 reported that the en bloc and complete resection rates were comparable between hybrid ESD and C-ESD, but the procedure time was shorter for hybrid ESD. The advantage of hybrid ESD is that the submucosal dissection step can be shortened with snaring. Hybrid ESD also enables safe resection of lesions in which access to the lesion is difficult because the ESD knife faces the muscle layer perpendicularly, such as in cecal lesions. In our study, RH-ESD was also used for patients in whom the endoscopic procedure had already been prolonged, which might explain why the procedure time was significantly longer with RH-ESD than with C-ESD or SH-ESD. ESD is likely to become more difficult as the procedure time increases because of intestinal edema and deterioration of peristalsis. Prolonged endoscopic treatment is not only more invasive for the patient but also affects the endoscopist’s concentration; therefore, the timing of switching from C-ESD to RH-ESD is important. The high perforation rate of the RH-ESD group likely reflects the fact that this group included patients in whom perforation occurred during C-ESD and snaring, and RH-ESD was applied for rescue purposes. Previous studies found no significant difference in the incidence of complications, including bleeding and perforation, between C-ESD and hybrid ESD.17,26 The wall of the large intestine is thinner than that elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract and is more susceptible to perforation than the stomach, making ESD more difficult. However, RH-ESD may be an option when resection is difficult, such as when the lesion is in the cecum or when severe fibrosis is present. Although RH-ESD has the advantage of shortening the submucosal dissection process by snaring difficult-to-treat areas, its indications have yet to be established. RH-ESD can be used in limited situations and should not be used in patients with inadequately dissected lesions or large tumors. As a method developed other than RH-ESD to overcome difficult situations during ESD, the traction method enables the endoscopist to obtain a good field of view and perform ESD procedures easily and safely. In the traction method, it is important to control the direction and strength of traction; however, one of the advantages of RH-ESD is that resection is possible regardless of traction. However, from the viewpoint of final resection using a snare, the disadvantage of RH-ESD is that it is difficult to control the depth of dissection when using a snare in lesions with a wide submucosal width, lesions with advanced fibrosis, and lesions with suspected submucosal invasion. Among C-ESD cases, RH-ESD showed a lower en bloc resection rate in difficult cases and perforation cases. Alternative treatment strategies are needed for cases in which C-ESD cannot be continued because of technical problems or complications such as perforation. In such cases, endoscopists may stop the procedure and refer the patients for surgical resection. However, if C-ESD cannot remove a lesion, RH-ESD should be considered as a practical option. While C-ESD has a high en bloc resection rate, hybrid ESD is associated with a higher local recurrence rate.24,27 Kang et al.24 identified failure of en bloc resection and large tumor size as risk factors for disease recurrence after endoscopic resection of colorectal lesions. The local recurrence rates were 0.7% for C-ESD, 2.4% for SH-ESD, and 4.2% for RH-ESD in this study, and all local recurrences could be controlled by additional EMR or hot biopsy. Therefore, from a practical standpoint, RH-ESD is clinically useful for avoiding surgery in cases of unsuccessful C-ESD despite its low curative resection rate.

Comparison of previous reports on clinical outcomes of hybrid ESD and conventional ESD for colorectal lesions

This study has several limitations. First, it has a retrospective design and was conducted at a single institution. Moreover, the endoscopic findings, including the tumor size, location, and morphology, were not uniform among the three groups, which may have introduced a degree of bias. Second, RH-ESD was not planned or performed at the endoscopist’s discretion during ESD, which may have affected the performance of the endoscopist. Third, this study included cases in which follow-up endoscopy after endoscopic resection was not possible. In view of the inadequate follow-up after endoscopic resection and the small number of cases, the long-term outcomes, including recurrence rates, may not be accurate. Therefore, a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trial is required in the future.

Sufficient submucosal dissection is required when performing RH-ESD to avoid piecemeal resection. RH-ESD for difficult or complicated C-ESD is an ineffective rescue procedure for curative resection. However, RH-ESD is useful for avoiding surgery in cases of unsuccessful C-ESD with a relatively low incidence of local recurrence.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Video 1.

Example of a scheduled hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure. A 30-mm flat, elevated lesion was found in the cecum. After injecting the submucosal layer with a mixture of 0.4% sodium hyaluronate solution, glycerol solution, and indigo carmine, a full circumferential incision was made outside the lesion. The submucosal layer was then dissected with an endoscopic submucosal dissection knife until it was sufficiently large to be safely resected en bloc with a snare. After adequate submucosal dissection, a local injection was administered to the submucosal layer, and the tip of the snare was placed on the mouth side of the lesion. The snare was then slowly opened to prevent the tip from shifting, and the lesion was strangulated for final resection. (https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.268.v1).

Supplementary Video 2.

Examples of a rescue hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure. For cases that were difficult to resect after a local injection was administered to the submucosa, RH-ESD was performed by snaring the lesion in the middle of the dissection. In cases of perforation, endoclips were used for closure. Because of the length of time of the procedure, local injection was administered after submucosal dissection, and snaring was performed for the lesion during dissection. (https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.268.v2).

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2022.268.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP21K20881). All authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank ThinkSCIENCE Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) for their English language assistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: HY, MF; Data curation: HY; Formal analysis: HY; Funding acquisition: HY; Investigation: HY, TMu, TMa, KU, YK, AM, TMo, SK, SN; Methodology: HY, NN, MS; Project administration: MF; Supervision: MF, TK, TI; Validation: HY; Writing–original draft: HY; Writing–review & editing: all authors.