CME for

KSGE members

Kim and Ahn: Unusual cause of persistent chest pain

Quiz

A 71-year-old man visited our hospital with one-month long chest pain. He was diagnosed with essential hypertension over the past 20 years. He had never undergone an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). He had lost 8 kg of body weight in the last 2 months. Initial EGD performed at another institution revealed a large mass in the thoracic esophagus.

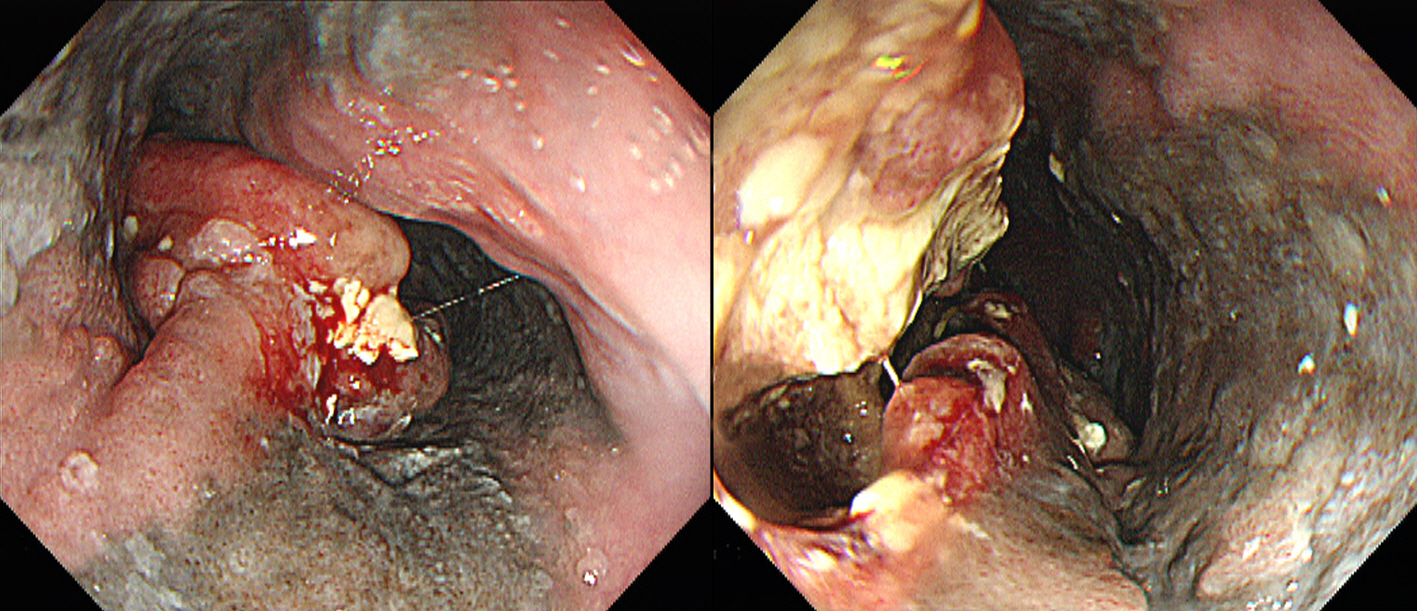

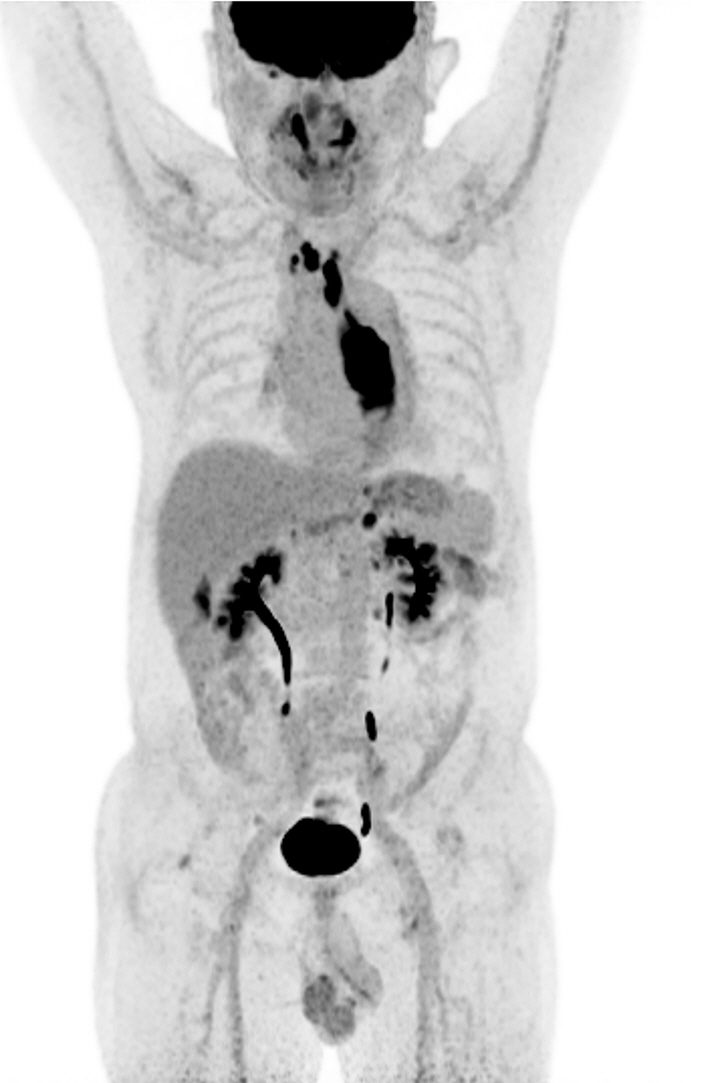

Physical examination revealed no remarkable findings. Blood test results were within the normal range, except for a C-reactive protein level of 1.04 mg/dL (normal range: less than 0.6 mg/dL). Reexamination with EGD at our hospital revealed a large ulceroinfiltrative mass occupying two-thirds of the esophageal lumen between the upper incisors at 22 and 34 cm ( Fig. 1). Chest and abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scans revealed focal esophageal wall thickening in the midesophagus and enlarged lymph nodes in the right upper paratracheal, left gastric, and retroperitoneal regions. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT (F-18 FDG PET-CT) revealed hypermetabolism in the affected areas ( Fig. 2). Histological findings and immunostaining results for cytokeratin, HMB45, P40, and S100 are shown ( Fig. 3). What was the most likely diagnosis?

Answer

Primary malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is an epithelial malignancy originating from melanocytes. 1 Melanocytes are derived from melanoblasts of the neural crest and migrate to the distal ileum via the omphalomesenteric canal to the distal ileum. 2 In the GI tract, metastatic melanoma is most commonly found in the small intestine (51%ŌĆō71%), stomach (27%), colon (22%), and esophagus (5%). 3,4 Primary malignant melanoma of the GI tract is extremely rare, and occurrences involving the esophagus are even rarer, accounting for approximately 0.1% to 0.5% of all esophageal malignancies. 5 It occurs in patients between the ages of 60 and 70 years and is twice as prevalent in men as in women. More than 90% of malignant melanomas of the esophagus occur mainly in the middle to distal third of the esophagus, which is speculated to be due to the high local concentration of melanocytes. 6 In comparison to other primary esophageal cancers, it progresses rapidly and has a poor prognosis. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 40.9% of patients already present with metastatic lesions; the average survival duration is 10 to 13 months, and the 5-year survival rate is 0% to 4%. 7

It is essential to rule out metastatic malignant melanoma by comprehensively analyzing the patientŌĆÖs history and physical examination, including the skin, eyes, and anus, which can be the initial sites of melanoma, before establishing a diagnosis of primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Through a full-body physical examination, the patient, in this case, was also confirmed to have no additional melanoma-suspected primary lesions. Endoscopic findings of primary esophageal melanoma typically reveal a lobulated, dark-colored tumor with intact mucosa or occasional ulcerations. 8 If a metastatic lesion is ruled out, the subsequent diagnosis is obtained through histopathologic examination. Given its frequent misdiagnosis as a poorly differentiated carcinoma, obtaining a sufficient number of specimens during tissue biopsy is important. The histopathologic diagnostic criteria for esophageal melanoma include the presence of melanin granules inside the tumor cells as well as melanocytes in the overlying esophageal epithelial layer. 8 In addition, accurate diagnosis can be obtained through immunohistochemical staining, which often reveals positive antibody-specific cytoplasmic reactivity to HMB-45 and S-100 proteins, and negative results for cytokeratin or carcinoembryonic antigen. 9 In CT images, melanoma is frequently observed as a bulky mass compressing the adjacent mediastinal structures. Differential diagnoses, including spindle cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, and esophageal lymphoma, should be established. F-18 FDG PET-CT detects melanoma as an FDG-avid lesion, making it an efficient diagnostic tool for confirming the disease burden. The patient was diagnosed with primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus with distant lymph node metastasis. The patient received seven months of palliative chemotherapy with pembrolizumab, but the disease progressed with esophageal stenosis and tracheal invasion. Chemotherapy was discontinued as the patientŌĆÖs condition deteriorated. The patient died eight months after being diagnosed with progressive disease.

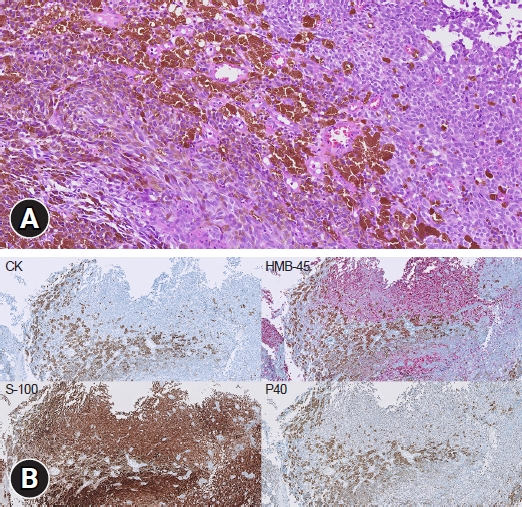

Fig.┬Ā1.

Endoscopic image of the esophageal mass. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy reveals a large ulceroinfiltrative mass occupying two-thirds of the esophageal lumen. Black mucosal pigmentation is observed around the mass.

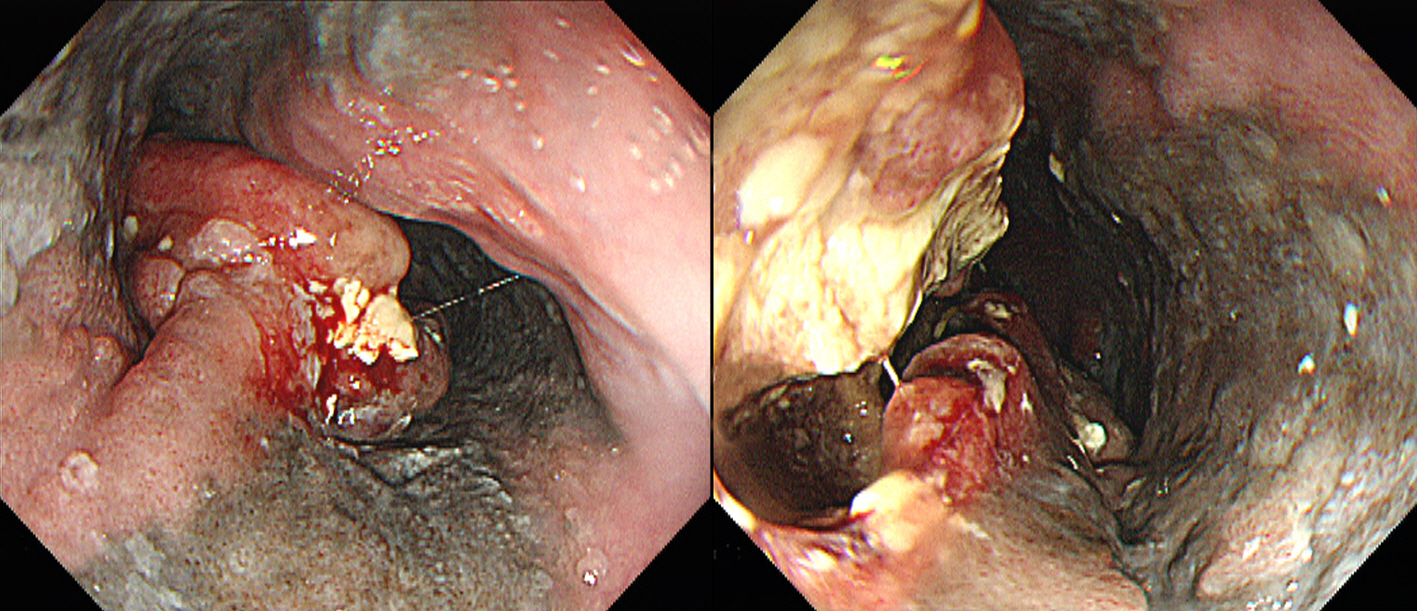

Fig.┬Ā2.

Coronal view of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography. A diffuse hypermetabolic mass is visible in the midthoracic esophagus. Multiple hypermetabolic lymph nodes are visible in the mediastinal, right upper paratracheal, upper paratracheal, and retroperitoneal regions.

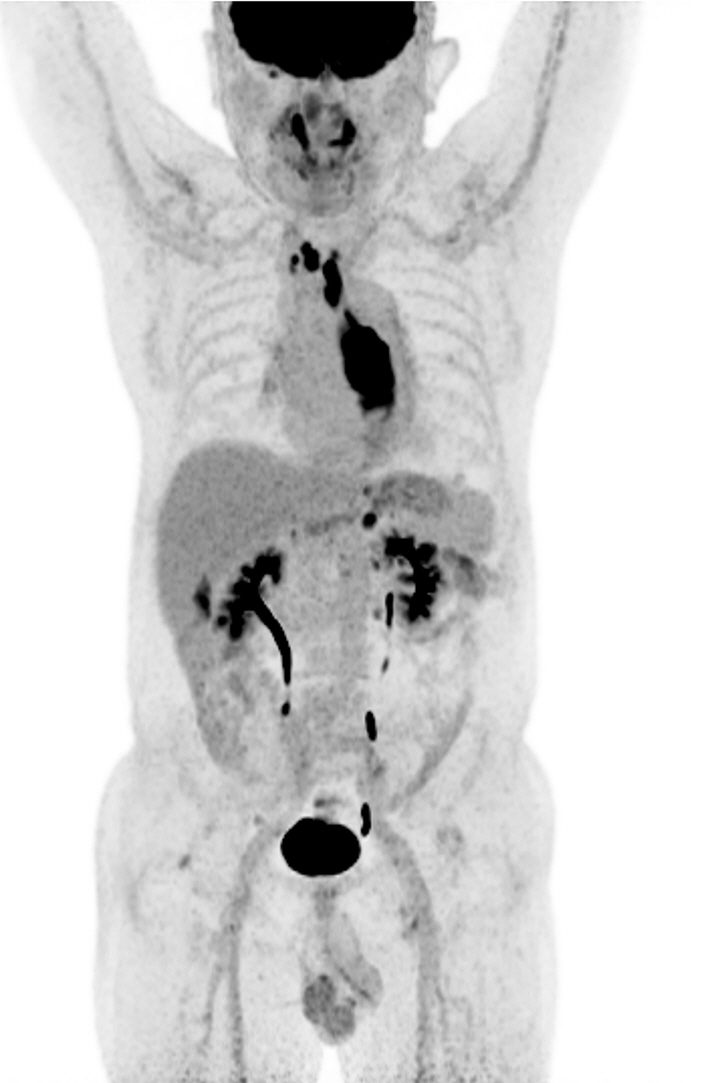

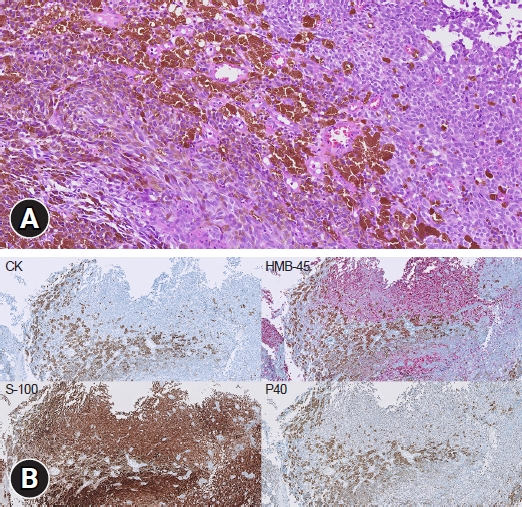

Fig.┬Ā3.

Histopathologic finding of the esophageal mass. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of the esophageal biopsy shows numerous black pigmented cells (├Ś20). (B) Immunohistochemistry staining showing HMB-45 and S-100 positivities. P40 is weakly positive, while cytokeratin (CK) is negative (├Ś10).

REFERENCES

1. De La Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickren JW, Cabrera A. Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer 1963;16:48ŌĆō50.  3. Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, Kochman ML. Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:3427ŌĆō3433.   4. L├│pez RG, Santom├® PM, Porto EI, et al. Intestinal perforation due to cutaneous malignant melanoma mestastatic implants. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2011;103:386ŌĆō388.   5. Caldwell CB, Bains MS, Burt M. Unusual malignant neoplasms of the esophagus. Oat cell carcinoma, melanoma, and sarcoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:100ŌĆō107.   6. Volpin E, Sauvanet A, Couvelard A, Belghiti J. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: a case report and review of the literature. Dis Esophagus 2002;15:244ŌĆō249.   7. Sabanathan S, Eng J, Pradhan GN. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84:1475ŌĆō1481.   9. Zheng J, Mo H, Ma S, Wang Z. Clinicopathological findings of primary esophageal malignant melanoma: report of six cases and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:7230ŌĆō7235.

|

|