INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori was discovered by Warren and Marshall, who reported it to be involved in the pathogenesis of gastritis and gastroduodenal ulcers.1 In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer designated H. pylori as a definite cause of gastric cancer.2 In Japan, the prevalence of H. pylori infection has decreased3; consequently, the incidence of H. pylori-related gastric cancer has decreased. However, the incidence of H. pylori infection-negative gastric cancer (HPNGC) is expected to increase. Therefore, it is important to understand the endoscopic and clinicopathological characteristics of gastric cancer that develops from gastric mucosa not infected with H. pylori. Several studies have sporadically reported on the clinicopathological and endoscopic features of HPNGC.4-8 However, few studies have conducted systematic analyses of the clinicopathological and endoscopic features in consecutive patients with HPNGC, including those with advanced gastric cancer.5 Additionally, there is a lack of studies examining the effectiveness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (M-NBI) for HPNGC. This study aimed to determine the clinicopathological and endoscopic features of HPNGC.

METHODS

Study design

This was a single-center retrospective study that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital (approval number: C22-04-003).

Patients

1) Inclusion criteria

The participants in this study were selected from a series of patients with gastric cancer who underwent endoscopic submucosal dissection or surgical resection at Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital between January 2013 and December 2021. Among them, patients with HPNGC were identified according to the definition of the stomach without H. pylori infection as presented in the following sections.

Methods

1) Definition of the stomach without H. pylori infection

The stomach without H. pylori infection was defined according to the following 3 criteria: characteristic endoscopic findings of the stomach without H. pylori infection9,10; no history of H. pylori eradication therapy; and negative results in at least 2 diagnostic tests for H. pylori infection (H. pylori IgG antibody test, urea breath test, stool antigen test, rapid urease test, biopsy specimen culture, and microscopic findings).

2) Endoscopic procedures

(1) Premedication and sedation

All patients underwent optimal preparation for endoscopy. Thirty minutes before the procedure, the patients were asked to drink an aqueous solution of mucolytic and defoaming agents.11 The formula consisted of 20,000 U pronase (Kaken Pharmaceutical), 1 g sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mL dimethylpolysiloxane (20 mg/mL; Horii Pharmaceutical) in 100 mL water. Most patients underwent sedation with intravenous injection of 3ŌĆō10 mg of diazepam (5 mg/mL; Takeda Pharmaceutical) or 2 to 8 mg of midazolam (5 mg/mL; Sandoz).

(2) Endoscopes

Endoscopic procedures were performed using electronic endoscopy systems (EVIS LUCERA ELITE, EVIS LUCERA SPECTRUM, VISERA ELITE II; Olympus Co.) featuring high-resolution upper gastrointestinal endoscopes with optical magnification (GIF-Q240Z, GIF-H260Z, GIF-H290Z, and GIF-XZ1200; Olympus Co.).

3) Endpoints

(1) Primary endpoints

The primary endpoint was clinicopathological and endoscopic features of HPNGC.

(2) Secondary endpoints

The diagnostic performance of M-NBI assessed using the vessel plus surface classification system12 for HPNGC was investigated as the secondary outcome.

RESULTS

Characteristics of target lesions and their clinicopathological features

Between January 2013 and December 2021, endoscopic or surgical resection was performed for 2,112 gastric cancer lesions at the Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital. Among them, 54 gastric cancer lesions (2.6%, 54/2,112) were negative for H. pylori infection. There were 2 advanced (0.1%, 2/2,112) and 52 early (2.5%, 52/2,112) gastric cancer lesions. Both advanced gastric cancer lesions were located in the cardia. There were slightly more women in the cohort. Macroscopically, elevated lesions were more common. Regarding lesion sites, more lesions were located in the upper part of the stomach. According to the depth of gastric wall invasion in the lesions of early gastric cancer, submucosal invasive cancer was observed in 16 lesions, and in all such lesions, the invasion was limited to the superficial part of the submucosal layer (<500 ╬╝m). Lymphovascular invasion was observed in 2 lesions, both of which were advanced gastric cancers (Table 1).

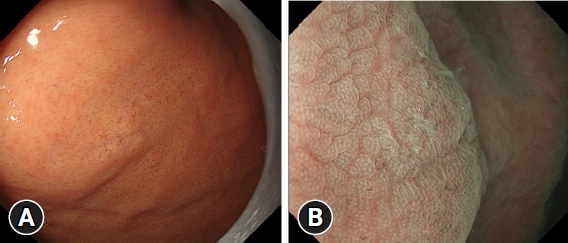

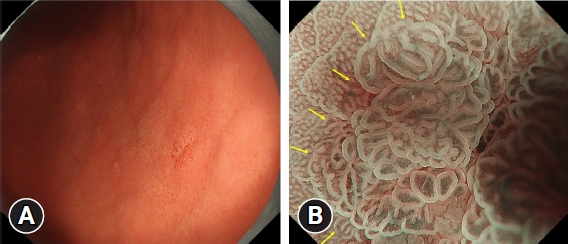

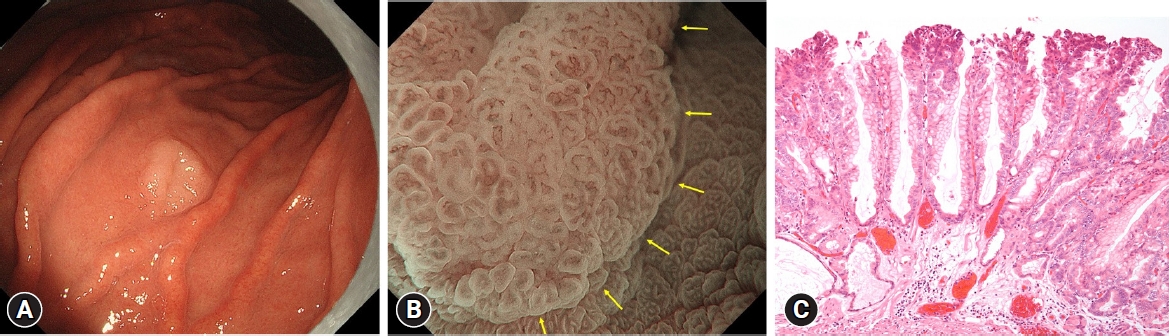

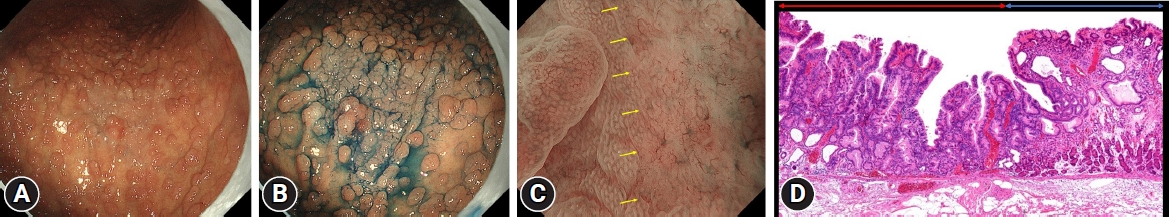

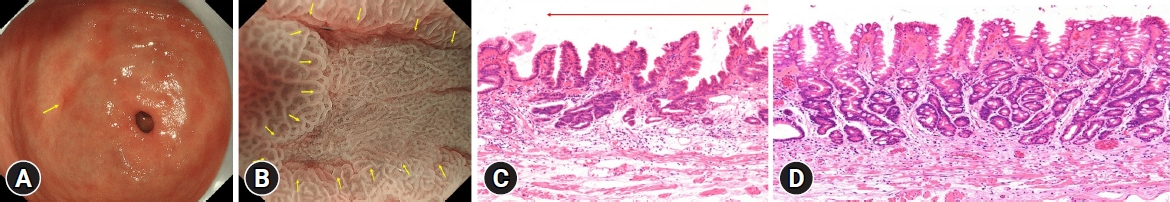

Next, HPNGC lesions were histopathologically classified (Table 2). There were 43 differentiated-type and 9 undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma lesions. The most common differentiated type of adenocarcinoma was gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland differentiation, which was observed in 30 lesions. Following further analyses of these 30 lesions, 15 were classified as adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type (Fig. 1), 13 were classified as adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland mucosa type (Fig. 2), and 2 were categorized as adenocarcinoma of mixed fundic and pyloric-mucosa type. Additionally, 3 lesions exhibited gastric adenocarcinoma of foveolar-type, consisting of one lesion with a whitish elevation (Fig. 3) and 2 lesions presenting as raspberry-like foveolar-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, there were 5 gastric adenocarcinoma lesions arising from polyposis, including 2 lesions observed in individuals with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and 3 lesions observed in individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis (Fig. 4). Gastric adenocarcinoma with autoimmune gastritis was observed in one lesion. Undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma was observed in 9 lesions, all of which were signet-ring cell carcinomas. Four well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma with low-grade atypia lesions were observed in the antrum (Fig. 5).

The morphology of the lesions was flat or depressed in all 9 lesions of signet-ring cell carcinoma, 3 lesions of well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma with low-grade atypia located in the antrum, 7 lesions of adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type, and one lesion of adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland mucosa type (total: 20/52, 38.5%). The other lesions exhibited an elevated morphology (61.5%, 32/52).

Histopathological examination was conducted on all resected specimens, revealing the presence of gastric intestinal metaplasia in the background mucosa of 3 lesions (5.6%; 3/54 lesions). All 3 lesions were well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinomas with low-grade atypia located in the antrum.

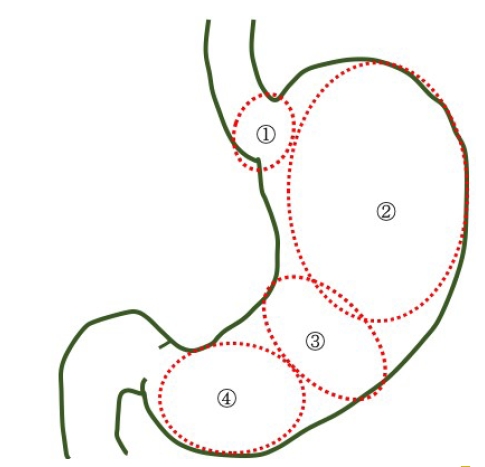

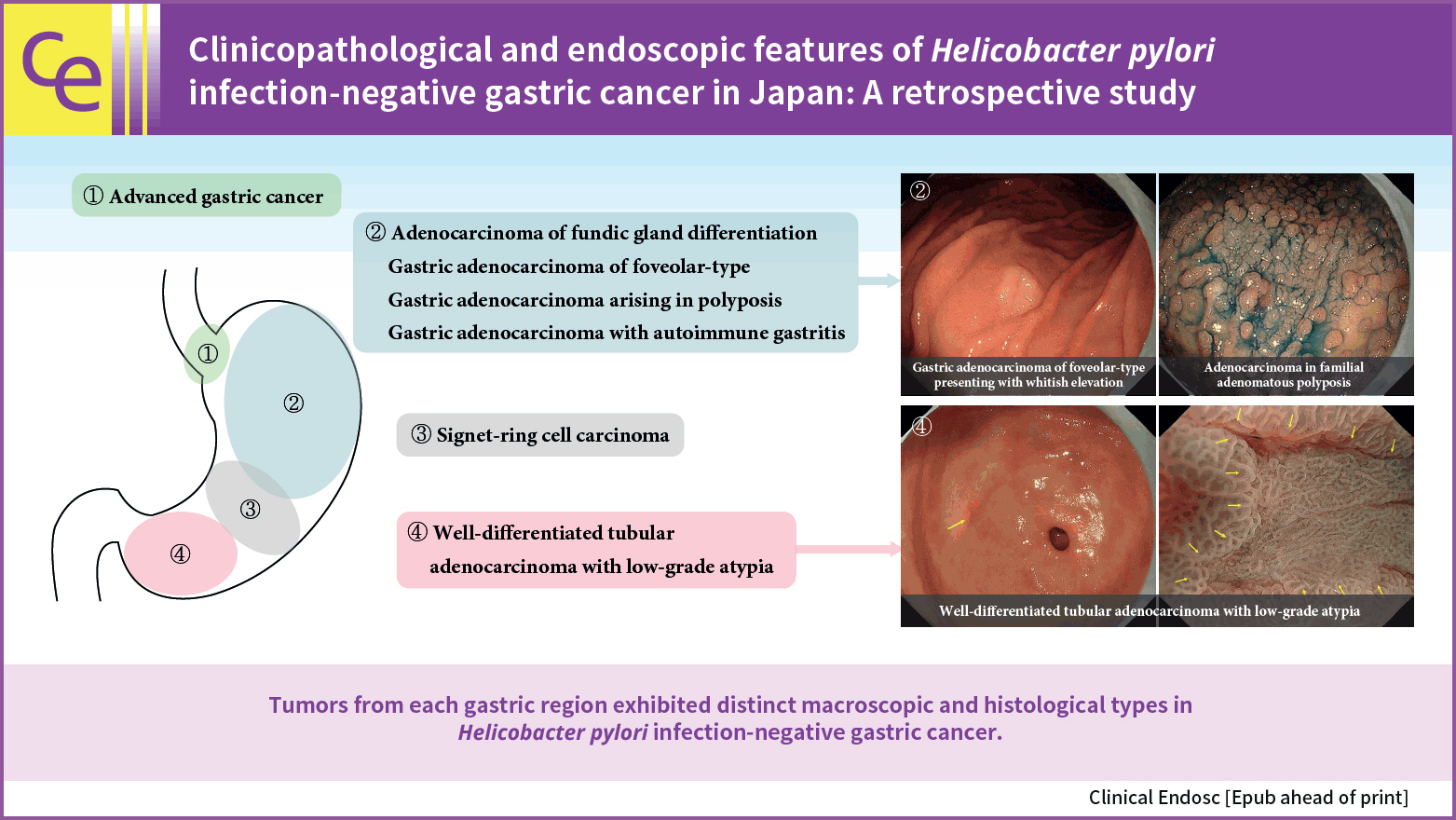

Characteristic histological findings and common sites of HPNGC

The current study revealed that the histological types and endoscopic findings of HPNGC differed among the 4 regions, as described below (Fig. 6).

1) Cardia

Advanced gastric cancer was observed in this region, with both lesions exhibiting an elevated morphology.

2) Fundic gland region ranging from the gastric fornix to the gastric body

This region comprised lesions of the following types: adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type (Fig. 1), adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland mucosa type (Fig. 2), and adenocarcinoma of mixed fundic and pyloric-mucosa types; gastric adenocarcinoma of foveolar-type presenting with whitish elevation (Fig. 3) and raspberry-like appearance; gastric adenocarcinoma arising in polyposis, including adenocarcinoma in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and adenocarcinoma in familial adenomatous polyposis (Fig. 4); and gastric adenocarcinoma with autoimmune gastritis.

Most lesions exhibited an elevated morphology (79.5%, 31/39).

3) Gastric-pyloric transition region ranging from the lower gastric body to the gastric angle

In this region, signet-ring cell carcinoma was observed. All lesions exhibited a flat or depressed morphology (100%, 9/9).

4) Antrum

Well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma with low-grade atypia (Fig. 5) was observed in this region. Most lesions exhibited a depressed morphology (75.0%, 3/4).

Diagnostic performance of M-NBI using the VS classification system for HPNGC

Three lesions that were difficult to evaluate by imaging were excluded, and 51 lesions were analyzed. The accuracy of M-NBI using the VS classification system for HPNGC diagnosis was 51.0% (26/51). No diagnosis could be made for 15 lesions of adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type (Fig. 1B), one lesion of adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland mucosa type, 2 lesions of mixed fundic and pyloric-mucosa type, and 7 lesions of signet-ring cell carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrated the clinicopathological and endoscopic features of HPNGC. The prevalence of HPNGC in the present study was 2.6% (54/2,112), which was comparable to that of 0.42% to 6.6% reported in previous studies.4-8

Herein, patients with H. pylori infection-negative advanced gastric cancer accounted for only 0.1% (2/2,112) of cases. Although HPNGC has been reported to be biologically less malignant than H. pylori infection-positive gastric cancer,13 there have been reports of advanced gastric cancer development in H. pylori infection-negative patients.14-16 The type of H. pylori infection-negative early gastric cancer that can rapidly progress to advanced gastric cancer remains unclear, which warrants further studies.

The current study revealed that tumors arising from different gastric regions exhibited distinct histological and endoscopic findings, including macroscopic types. Herein, advanced gastric cancer occurred in the cardia region. In the fundic gland region ranging from the gastric fornix to the gastric body, adenocarcinomas of fundic-gland differentiation (adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type,17 adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland mucosa type,18,19 and adenocarcinoma of mixed fundic and pyloric-mucosa type20,21), gastric adenocarcinoma of foveolar-type (gastric adenocarcinoma of foveolar-type presenting with whitish elevation6,7 and raspberry-like foveolar-type gastric adenocarcinoma22), gastric adenocarcinoma arising in polyposis (adenocarcinoma in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and adenocarcinoma in familial adenomatous polyposis), and gastric adenocarcinoma with autoimmune gastritis23 were observed. Signet-ring cell carcinoma was observed in the gastric-pyloric transition region ranging from the lower gastric body to the gastric angle.24,25 A well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma with low-grade atypia26 was observed in the antrum. Regarding the macroscopic characteristics, lesions located in the fundic gland region ranging from the gastric fornix to the gastric body were characterized by an elevated morphology, while lesions located in the gastric-pyloric transition region ranging from the lower gastric body to the gastric angle were characterized by a flat or depressed morphology. The current study revealed that the risk of advanced gastric cancer development might be present at the cardia and that it might be possible to diagnose early gastric cancer based on specific background endoscopic features. The detection of gastric cancer during endoscopic screening in patients with H. pylori infection-negative cancer may be achieved if the endoscopist is aware of the characteristic endoscopic findings and the specific localization within the stomach, which have been demonstrated in this study.

Herein, HPNGC lesions were predominantly observed in the fundic gland (72.2%, 39/54). Given that the fundic gland region has many blind spots that are hidden by greater curvature plication during the endoscopic screening of the intragastric region, extending and carefully observing the gastric wall is critical. Tumors mimic the morphology and function of their origins. Therefore, epithelial tumors arising from the H. pylori infection-negative stomach resemble cells and tissues of the proper gastric mucosa without intestinal metaplasia.27 The fundic glands are widely distributed in the gastric mucosa except for relatively small regions containing the cardiac or pyloric glands. This may explain why HPNGC was often observed in the fundic gland region in this study. In addition, it is a well-known fact that gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland differentiation arises from the mucosa in the fundic gland region. The inclusion of several patients with this type of tumor in this study may be an additional reason for the frequent observation of HPNGC within the fundic gland mucosa. The current study confirmed gastric intestinal metaplasia, even in background mucosa without H. pylori infection, in 3 lesions, all located in the antrum. Recently, bile reflux has been linked to gastric intestinal metaplasia.28-31 The development of intestinal metaplasia may be attributable to the predisposition of the antrum to bile reflux.

M-NBI showed that 27 lesions (53%) of HPNGC met the diagnostic criteria for cancer according to the VS classification system, and no diagnosis could be made for 15 lesions of adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type, one lesion of adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland mucosa type, 2 lesions of adenocarcinoma of mixed fundic and pyloric-mucosa type, and 7 lesions of signet-ring cell carcinoma. A histological architecture that makes diagnosis using M-NBI difficult is the superficial layer of the intramucosal tumor tissue being widely covered by non-tumor epithelium, as seen in adenocarcinoma of the fundic-gland type and some undifferentiated-type adenocarcinomas. Such lesions require the histological examination of biopsy specimens for definite diagnosis.

The limitation of the current study is its single-center retrospective design.

In conclusion, the study findings demonstrated that HPNGC originating from various regions of the stomach exhibited distinct endoscopic characteristics and histological types. These specific features related to cancer sites should be considered when performing screening endoscopies for individuals with H. pylori infection-negative stomach to enhance diagnostic accuracy and effectiveness.