AbstractBackground/AimsCombination of midazolam and opioids is used widely for endoscopic sedation. Compared with meperidine, fentanyl is reportedly associated with rapid recovery, turnover rate of endoscopy room, and quality of endoscopy. We compared fentanyl with meperidine when combined with midazolam for sedative colonoscopy.

MethodsA retrospective, cross-sectional, 1:2 matching study was conducted. Induction and recovery time were compared as the primary outcomes. Moreover, cecal intubation time, withdrawal time, total procedure time of colonoscopy, paradoxical reaction, adenoma detection rate, and adverse effect of midazolam or opioids were assessed as the secondary outcomes.

ResultsA total of 129 subjects (43 fentanyl vs. 86 meperidine) were included in the analysis. The fentanyl group showed significantly more rapid induction time (4.5ТБ2.7 min vs. 7.5ТБ4.7 min, p<0.001), but longer recovery time (59.5ТБ25.6 min vs. 50.3ТБ10.9 min, p=0.030) than the meperidine group. In multivariate analysis, the induction time of the fentanyl group was 3.40 min faster (p<0.001), but the recovery time was 6.38 min longer (p=0.046) than that of the meperidine group. There was no difference in withdrawal time and adenoma detection rate between the two groups.

INTRODUCTIONThe incidence of colorectal cancer is increasing in Korea owing to westernized lifestyle. Colorectal cancer has the second highest incidence among cancers and is the third-leading cause of cancer-related death in Korea [1,2]. Screening or diagnostic colonoscopy may decrease colorectal cancer incidence and mortality [3].

There are four levels of sedation, as defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). Among them, moderate sedation/analgesia is characterized by purposeful response to tactile or verbal stimulation. It is also called conscious sedation and it has been considered an appropriate state for gastrointestinal endoscopy [4-6].

Sedative drugs, such as benzodiazepines, relieve anxiety in a subject and exert amnestic effect during the endoscopic procedure. However, as benzodiazepines have little analgesic effect, they are usually administered concomitantly with opioids, such as meperidine or fentanyl, for colonoscopy. A combination of midazolam and opioids is used for sedative endoscopy, and it can increase the quality of endoscopy while decreasing the dose of sedative drugs and the incidence of adverse events [7,8]. The most common opioids used in combination with benzodiazepines for sedative endoscopy are fentanyl and meperidine. Fentanyl has a faster onset time and shorter duration than meperidine [9]. Thus, fentanyl is widely used in western countries, but not in Korea [10]. If meperidine and fentanyl has similar analgesic effect during endoscopy, the latter is superior in terms of relatively rapid onset, early recovery, fast turnover rate of endoscopy room, and quality of endoscopy. The aim of this study was to compare fentanyl and meperidine when combined with midazolam for screening or diagnostic colonoscopy in the Korean population.

MATERIALS AND METHODSStudy populationsA retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted in patients who received sedation for screening or diagnostic colonoscopy between December 2017 and January 2018 at Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital. Subjects over 19 years old were included.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) colonoscopy was performed for screening or diagnostic purposes; (2) colonoscopy was conducted following esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) without recovery on the same session; (3) patients who had bowel preparation by polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid (CoolPrep POWDERТЎ; Taejoon Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). For bowel preparation, the Aronchick bowel preparation scale was used.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) colonoscopy was performed for non-screening or non-diagnostic purposes, such as cancer surveillance or follow-up of inflammatory bowel disease; (2) patients who received therapeutic procedures, i.e., polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection; (3) patients who used propofol; (4) patients who underwent colonoscopy only or colonoscopy before EGD; (5) patients who underwent bowel preparation by other substances than polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid.

The institutional review board of Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital approved this study (DUIH 2019-11-035).

Study designStandard colonoscopy (CF-H260AL or CF-HQ290L; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) was performed by six endoscopists working in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital. All the endoscopists had performed at least 300 colonoscopic examinations.

Unified sedation protocol was maintained for every subject. Midazolam was administered intravenously at 0.05 mg/kg (Bukwang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) with 50 ТЕg fentanyl (Hanlim Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) or 50 mg meperidine (BCworld Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) before endoscopic examination. If a subject had not achieved moderate sedation, an additional dose of 1т2 mg (0.02т0.03 mg/kg) midazolam was administered at 2т3 min intervals. An additional dose of 25 ТЕg fentanyl or 25 mg meperidine was administered if a subject had not manifested adequate analgesia. A 30% reduced dose of midazolam in combination with 25 ТЕg fentanyl or 25 mg meperidine was administered in subjects over 65 years of age or with ASA physical status of 3 or higher [11,12]. After completion of colonoscopy, flumazenil, an antagonist of benzodiazepine, was administered routinely to the subjects.

The subjects were categorized into two groups: one was treated fentanyl with midazolam (fentanyl group) and the other with meperidine with midazolam (meperidine group). The meperidine group was 1:2 matched to the fentanyl group according to age and sex. Induction time and recovery time were compared as the primary outcomes between the groups. Cecal intubation time, withdrawal time, total procedure time of colonoscopy, paradoxical reaction of midazolam, adenoma detection rate, and adverse events of midazolam or opioids were assessed as the secondary outcomes. Induction time was defined as the time from midazolam administration to the start of endoscopy, and recovery time was defined as the time from midazolam administration to the point of discharge. The time of midazolam administration or discharge was obtained from sedation records, and the time of the first endoscopic image was regarded as the start of endoscopy. We decided the point of discharge based on the тModified Aldrete scoring systemт [13].

Statistical analysisIndependent two-sample t-test was used for univariate analysis of age, induction time, recovery time, cecal intubation time, withdrawal time, total procedure time, total dose of midazolam, and total dose of opioids. Chiтsquare test was used for univariate analysis of sex, ASA physical status, bowel preparation, additional administrations of midazolam and opioids, paradoxical reaction of midazolam, adverse events of midazolam or opioids, and adenoma detection. For multivariate analysis, a generalized linear model was used as appropriate. The model included age, sex, weight, body mass index (BMI), midazolam dose, ASA status, bowel preparation, adenoma detection, additional midazolam, and additional opioids, as well as opioids (fentanyl vs. meperidine). All two-sided p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

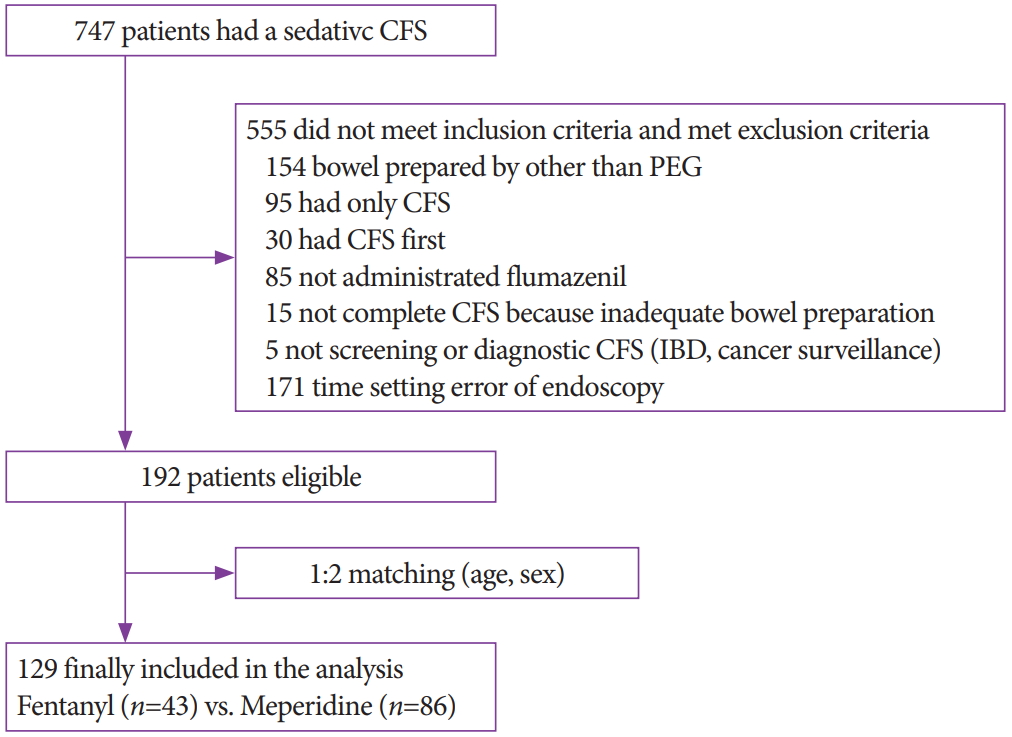

RESULTSA total of 747 subjects received sedative colonoscopy during the study period. After exclusions, subjects in the meperidine group were 1:2 matched to the 43 subjects in the fentanyl group. Finally, 129 subjects (43 in the fentanyl group and 86 in the meperidine group) were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

The baseline characteristics of the two groups showed no difference in age, age over 65 years, sex, height, body weight, BMI, ASA score, bowel preparation, and total dose of midazolam (Table 1). However, administration of an additional dose of midazolam and opioids was more frequent in the fentanyl group. In the fentanyl group, the mean total dose of midazolam was 5.2 mg and the mean total dose of fentanyl was 57.0 ЮМg. In the meperidine group, the total dose of midazolam was 4.9 mg and the total dose of meperidine was 45.6 mg. Additional midazolam was administered to 22 (51.2%) out of 43 subjects in the fentanyl group and to 24 (27.9%) out of 86 in the meperidine group (p=0.009). An additional dose of fentanyl was administered to 12 (27.9%) subjects and additional meperidine to 8 (9.3%) subjects (p=0.006).

In the univariate analysis, induction time was 4.5 and 7.5 min in the fentanyl and meperidine groups, respectively (p=0.001) (Table 2). Recovery time was 59.5 and 50.3 min in the fentanyl and meperidine groups (p=0.030). There was no difference in the secondary outcomes between the two groups. There was no difference in terms of adverse events (desaturation or hypotension, 0% vs. 2.3%, p=0.314; nausea or vomiting, 0% vs. 1.2%, p=0.478) between the fentanyl and meperidine groups. In the multivariate analysis, induction time in the fentanyl group was 3.40 min faster (95% confidence interval [CI], т4.93 to т1.87; p<0.001), but the recovery time was 6.38 min longer (95% CI, 0.12 to 12.65; p=0.046) than those in the meperidine group (Table 3). Although cecal intubation time was 0.82 min faster and total procedure time was 0.66 min shorter in the fentanyl group than those in the meperidine group, the differences were not significant (p=0.340 and 0.535, respectively). There also was no difference in adenoma detection between the two groups (odds ratio=1.14; 95% CI, 0.41 to 3.14; p=0.807).

DISCUSSIONModerate sedation has been considered an appropriate state for most gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures [4,5]. Fentanyl and meperidine are the most common opioids used in combination with midazolam for sedative endoscopy. The use of fentanyl or meperidine with midazolam allows reduction of the dose of midazolam, thereby decreasing the adverse effect of midazolam and increasing the comfort and accuracy of endoscopic examination [14]. Fentanyl has similar analgesic effect to that of meperidine. However, fentanyl has faster onset time and shorter duration than meperidine. Because fentanyl releases histamine to a lower extent than meperidine, fentanyl has fewer adverse reactions, such as nausea and vomiting [8,15]. Fentanyl is safer than meperidine in patients with liver disease, such as cirrhosis [16]. Moreover, fentanyl affects the cardiovascular system to a lower extent than meperidine [8]. Therefore, according to studies in western countries, fentanyl is better in terms of turnover rate of endoscopy room, quality of endoscopy, and subject satisfaction. In a study of 1,385,436 colonoscopies performed in the United States from 2000 to 2013, fentanyl was used in 614,707 subjects and meperidine was used in 421,546 subjects. The proportion of meperidine use decreased, whereas that of fentanyl use increased [10]. However, fentanyl use is currently not very popular in Korea because fentanyl is more expensive than meperidine. In addition, most endoscopists traditionally use meperidine instead of fentanyl.

According to our data, recovery time was unexpectedly longer in the fentanyl group. It was thought that this result came from the additional administrations of midazolam and fentanyl itself. Because fentanyl has shorter duration and faster recovery than meperidine, additional administrations of midazolam or opioid tended to be required in the fentanyl group. Furthermore, the proportion of healthy subjects with ASA score 1 was higher in the fentanyl group than in the meperidine group (79.1% vs. 62.8%), even though the difference was not significant. Therefore, additional administrations of midazolam or opioids may result in longer recovery time in the fentanyl group. Midazolam and opioids were administered before or during endoscopy according to the sedation status of the subjects. In addition, the total procedure time of EGD plus colonoscopy can affect recovery time. The total procedure time of colonoscopy was not different between the fentanyl and meperidine groups in the present study. We did not evaluate the procedure time of EGD; however, as we did not include therapeutic EGD, the procedure time of screening EGD would not be different between the two groups, either.

Moreover, the possibility of ethnic influence was not excluded. As the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of analgesics, such as fentanyl and meperidine, have been studied mainly in western countries, there may be differences in the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and effect of drugs between the western and Korean populations. In addition, it is possible that routine administration of flumazenil in our institute affected the recovery time of the fentanyl and meperidine groups differently. Further analysis with larger samples is needed to identify subgroups that may benefit more from fentanyl or meperidine.

Our study had several limitations. This was a single center study. In addition, the number of subjects analyzed was relatively small, and the study was designed retrospectively. Therefore, we could not generalize the results of our study. In addition, there was no evaluation of subject satisfaction and the level of discomfort as assessed by endoscopists felt with regard to sedative endoscopy. Even though we adjusted ASA score for the study, underlying conditions, such as chronic renal disease, may have affected the recovery time of analgesics, which can be a confounding factor. Prospective, large, randomized controlled trials with examination of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles for the Korean population are expected in the future.

In conclusion, the fentanyl group had more rapid sedation induction time but had longer recovery time than the meperidine group. The two groups showed no significant difference in withdrawal time and adenoma detection rate, which are quality control indicators of colonoscopy.

NOTESAuthor Contributions

Conceptualization: Jun Kyu Lee, Dong Kee Jang

Data curation: Gwan Woo Hong, Jung Hyeon Lee

Formal analysis: Ji Hun Bong, Sung Hun Choi, Hyeki Cho

Methodology: Ji Hyung Nam, Jae Hak Kim, Yun Jeong Lim

Writing-original draft: GWH, JKL

Writing-review&editing: Hyoun Woo Kang, Moon Soo Koh, Jin Ho Lee

Fig.Т 1.Study population. CFS, colonoscopy; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PEG, polyethylene glycol.

TableТ 1.Baseline Characteristics TableТ 2.Univariate Analysis of the Primary and Secondary Outcomes TableТ 3.Multivariate Analysis of the Primary and Secondary Outcomes: Comparison of Outcomes between Fentanyl and Meperidine REFERENCES1. Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat 2019;51:417т430.

2. Vital Statistics Division; Statistics Korea, Shin HY, Lee JY, et al. Cause-of-death statistics in 2016 in the Republic of Korea. J Korean Med Assoc 2018;61:573т584.

3. Pan J, Xin L, Ma YF, Hu LH, Li ZS. Colonoscopy reduces colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in patients with non-malignant findings: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:355т365.

4. Obara K, Haruma K, Irisawa A, et al. Guidelines for sedation in gastroenterological endoscopy. Dig Endosc 2015;27:435т449.

5. Triantafillidis JK, Merikas E, Nikolakis D, Papalois AE. Sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy: current issues. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:463т481.

6. Lee TH, Lee CK. Endoscopic sedation: from training to performance. Clin Endosc 2014;47:141т150.

8. Cohen LB, Delegge MH, Aisenberg J, et al. AGA institute review of endoscopic sedation. Gastroenterology 2007;133:675т701.

9. Horn E, Nesbit SA. Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of sedatives and analgesics. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2004;14:247т268.

10. Childers RE, Williams JL, Sonnenberg A. Practice patterns of sedation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:503т511.

11. Phillips SN, Fernando R, Girard T. Parenteral opioid analgesia: does it still have a role? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2017;31:3т14.

12. Hinkelbein J, Lamperti M, Akeson J, et al. European Society of Anaesthesiology and European Board of Anaesthesiology guidelines for procedural sedation and analgesia in adults. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2018;35:6т24.

14. Jin EH, Hong KS, Lee Y, et al. How to improve patient satisfaction during midazolam sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy? World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:1098т1105.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||